C ONTENTS

F OR P EG

sine qua non

A UTHOR S N OTE

T he idea for this book first occurred to me ten years ago while reading a medieval account of the legendary quarrel between Jean de Carrouges and Jacques Le Gris. Fascinated by the story, I began collecting everything I could find about the CarrougesLe Gris affair. Eventually I traveled to Normandy and Paris to explore manuscript archives and experience the places where the drama unfolded more than six hundred years ago. The resulting book is a true story based on original sources: chronicles, legal records, and other surviving documents. All persons, places, dates, and many other detailsincluding what people said and did, their often contradictory claims in court, sums of money paid or received, even the weatherare real and based on the sources. Where the sources disagree, I give the most likely account of events. Where the historical record is silent, I use my own invention to fill in some of the gaps, while always listening closely to the voices of the past.

P ROLOGUE

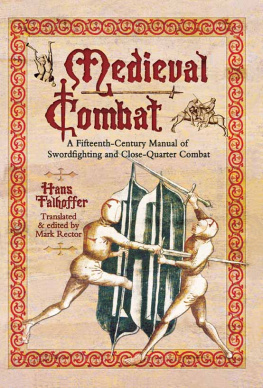

O n a cold morning a few days after Christmas in 1386, thousands of people packed a large open space behind a monastery in Paris to watch two knights fight a duel to the death. The rectangular field of battle was enclosed by a high wooden wall, and the wall was surrounded by guards armed with spears. Charles VI, the eighteen-year-old king of France, sat with his court in colorful viewing stands along one side, while the huge throng of spectators crowded all around the field.

The two combatants, in full armor, swords and daggers at their belts, sat facing each other across the length of the field on thronelike chairs placed just outside the heavy gates at either end. Attendants held a stamping warhorse ready by each gate, as priests hurriedly cleared the field of the altar and crucifix on which the two enemies had just sworn their oaths.

At the marshals signal, the knights would mount their horses, seize their lances, and charge onto the field. The guards would then slam the gates shut, imprisoning the two men inside the heavy stockade. There they would fight without quarter, and without any chance of escape, until one killed the other, thus proving his charges and revealing Gods verdict on their quarrel.

The excited crowd was watching not only the two fierce warriors, and the youthful king amid his splendid court, but also the beautiful young woman sitting alone on a black-draped scaffold overlooking the field, dressed from head to toe in mourning, and also surrounded by guards.

Feeling the eyes of the crowd upon her and bracing herself for the coming ordeal, she stared ahead at the flat, smooth field where her fate would soon be written in blood.

If her champion won the judicial combat and killed his opponent, she would go free. But if he were slain, she would pay with her life for having sworn a false oath.

It was the feast day of the martyred saint Thomas Becket, the crowd was in a holiday mood, and she knew that many were eager to see not only a man slain in mortal combat but also a woman put to death.

As the bells of Paris tolled the hour, the kings marshal strode onto the field and held up a hand for silence. The trial by combat was about to begin.

C ARROUGES

I n the fourteenth century it took several months for knights and pilgrims to travel from Paris or Rome to the Holy Land, and a year or more for friars and traders to journey across Europe and all the way to China along the Silk Road. Asia, Africa, and the still-undiscovered Americas had not yet been colonized by Europeans. And Europe itself had been nearly conquered by Muslim horsemen, who stormed out of Arabia in the seventh century, sailed from Africa to capture Sicily and Spain, and crossed swords with Christians as far north as Tours, France, before being turned back. By the fourteenth century, Christendom had faced the Muslim threat for more than six hundred years, launching repeated crusades against the infidel.

When not united against its common foe, Christendom was often at war with itself. The kings and queens of Europe, a large extended family of brothers and sisters and intermarried cousins, squabbled and fought with one another continually over thrones and territory. The frequent wars among Europes feuding monarchs reduced towns and farmland to smoking ruins, killed or starved the people, and left rulers with huge debts that they paid by raising taxes, debasing the coinage, or simply seizing the wealth of convenient victims like Jews.

S OLDIERS P ILLAGE A H OUSE.

English soldiers plundered many parts of France during the Hundred Years War. Chronique du Religieux de Saint-Denys. MS. Royal 20 C VII., fol. 41v. By permission of the British Library.

At the center of Europe lay the Kingdom of France, a vast realm that took twenty-two days to cross from north to south, and sixteen days from east to west. France, the forge of feudalism, had endured for nearly ten centuries. Founded amid the ruins of Roman Gaul in the fifth century, it had been Charlemagnes fortress against Islamic Spain in the ninth, and it was Europes richest, most powerful nation at the start of the fourteenth. But within a few decades Fortune had turned against France, and the nation was now desperately fighting for its survival.

In 1339 the English crossed the Channel and invaded France, beginning the long, ruinous conflict that would be known as the Hundred Years War. After cutting down the flower of French chivalry at Crcy in 1346, the English captured Calais. A decade later at Poitiers, amid another great slaughter of French knights, the English seized King Jean and took him to London, releasing their royal prisoner only in exchange for vast French territories, many noble hostages, and promises to pay a colossal ransom of three million gold cus.

Stunned by the loss of its king and what it cost to buy him back, France fell into civil war. Rebellious nobles betrayed King Jean and joined with the English invaders, peasants enraged by new taxes rose up to murder their lords, and the volatile citizens of Paris split into feuding factions and butchered one another in the streets. Chronic droughts and crop failures added to the misery of the people. And the Great Plague that carried off a third of Europe in 134849, leaving unburied corpses scattered over fields and stacked in the streets, kept returning every decade or so for another grim harvest.