Preface

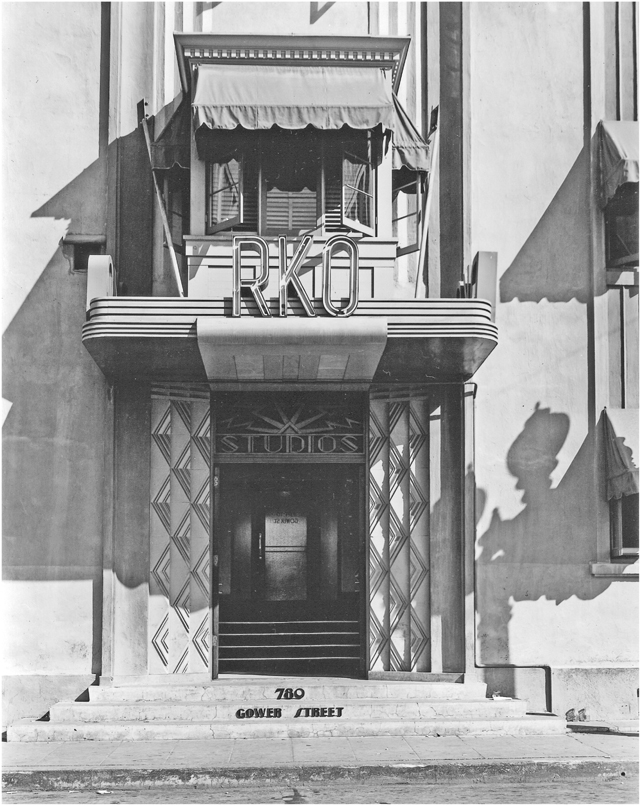

This volume completes my business history of RKO Radio Pictures, one of Hollywoods classical motion picture companies. The first half of the project, RKO Radio Pictures: A Titan Is Born, published by the University of California Press in 2012, covers the prehistory of the company through the first half of 1942. This second work picks up the narrative at that historical moment and chronicles the companys most successful era, as well as its decline and eventual death in 1957.

For those who have not read the first volume, a brief overview is in order. RKO came into existence in 1928 because the Radio Corporation of America needed an outlet and showcase for its newly perfected Photophone movie sound recording and reproduction equipment. But David Sarnoff of RCA, one of the pioneers of broadcasting in America, had a grand vision that ranged far beyond sound engineering. He looked forward to a day when radio, the movies, music recordings, theater, vaudeville and even television (then in the planning stages at RCA) would be combined in a symbiotic entertainment conglomerate, each component of which could support and invigorate the others. In short, Sarnoff envisioned the future of global entertainment, though he was unable to bring the dream to fruition during his lifetime.

One reason was the Great Depression, which demolished the dreams of many. Before the Hollywood industry began to suffer the effects of the nations economic decline, Sarnoffs RKO performed nicely, posting decent profits in 1929 and 1930 despite mediocre early product. But then theater attendance throughout America executed a startling belly flop and, by 1933, RKO was essentially bankrupt. Thanks to the receivership provisions of the U.S. banking codes, the company continued to produce, distribute, and release movies, though it would not be fiscally whole again until 1940. Nevertheless, many of its most famous films came out during this difficult period: King Kong, nine Astaire-Rogers musicals including Top Hat and Swing Time, the multiple award-winning drama The Informer, the hilarious screwball comedy Bringing Up Baby, the rollicking adventure Gunga Din, and a spectacular version of the Victor Hugo classic The Hunchback of Notre Dame.

Soon after RKO emerged from receivership in 1940, it began to falter again. The corporate president at that time was George J. Schaefer, a dynamic executive who believed the RKO brand should stand for quality entertainment that would make it the most distinguished and respected of film companies. But the path Schaefer chose to that goal was riddled with potholes. Even Schaefers greatest triumph, the Orson Welles masterpiece Citizen Kane, backfired on him, opening RKO up to the wrath of journalistic tycoon William Randolph Hearst, who interpreted Kane as an unflattering portrait of himself. Hearst mounted an effective campaign to stymie the release of the picture, causing Schaefers finest film to flop at the box office. Most of the other RKO productions released in 1941 and the first half of 1942 also fizzled, bringing the company close to receivership once again. It is at this point, some six months after the United States entry into World War II, that we pick up the story.

George Schaefer was RKOs fourth corporate president in its fourteen-year history. The company had also employed nine heads of production by that time. RKOs direct competitorsMGM, Paramount, Warner Bros., Twentieth CenturyFoxendured much less turnover in these two crucial executive positions. Those vertically integrated outfits (like RKO, each had production, distribution, and exhibition components) consistently outdistanced RKO in profitability, and one of the primary reasons for their success was executive stability. The absence of continuity at the management level as well as a consistent business philosophy became RKOs Achilles heel, turning the company into the little kid who constantly chased, but never managed to catch, the big boys.

While a problem at the business level, instability made RKO, in many ways, the most fascinating of all the great American movie companies. It was never business as usual at RKO; the company existed in a perpetual state of reinvention. Consequently, many interesting and talented people were drawn to the organization, and their efforts often produced memorable results, from movies to picture personalities to astounding feats of promotion.

At the risk of redundancy, I will once again emphasize that this book is a business history and quote a passage from my introduction to the first volume:

Of course, theatrical motion pictures have always been more than just a business. They are also an art form, a technological phenomenon, a medium of communications, and an influential conveyor of popular culture, and RKO certainly made important contributions in each of these areas. Unfortunately, the scholarship related to Hollywood and its films is often unbalanced, emphasizing artists and artistic achievements while ignoring or even attacking the industrial basis of all production. What many scholars tend to downplay is one simple fact: the films they admire or believe are worth discussing would never have been produced if executives had not believed they would make money for their companies.

Choosing to approach the history of RKO from a business perspective sometimes places me in the awkward position of presenting negative assessments of films and individuals I admire. But just because a movie is aesthetically brilliant and stands the test of time does not mean it was a boon to the company that made it. Many of the greatest cinematic works failed at the box office when first released. From a business perspective, such artists as Howard Hawks and Orson Welles and such films as Bringing Up Baby and Citizen Kane were bad news for RKO, and the problems they spawned will be detailed in this study. There are plenty of other scholarly works that analyze the excellence of such films; this book will consider them from a different point of viewas commercial products expected to generate substantial revenue.