When I was a boy, I had a strange recurring daydream. I saw myself stuck in a small space, barely big enough to lie down in. Curled up on the floor, I knew that I would be there for a long time. I couldnt leave, but I didnt mind. There was something about the challenge of living in such a small space that was appealing to me. I felt I had everything I needed and was where I belonged.

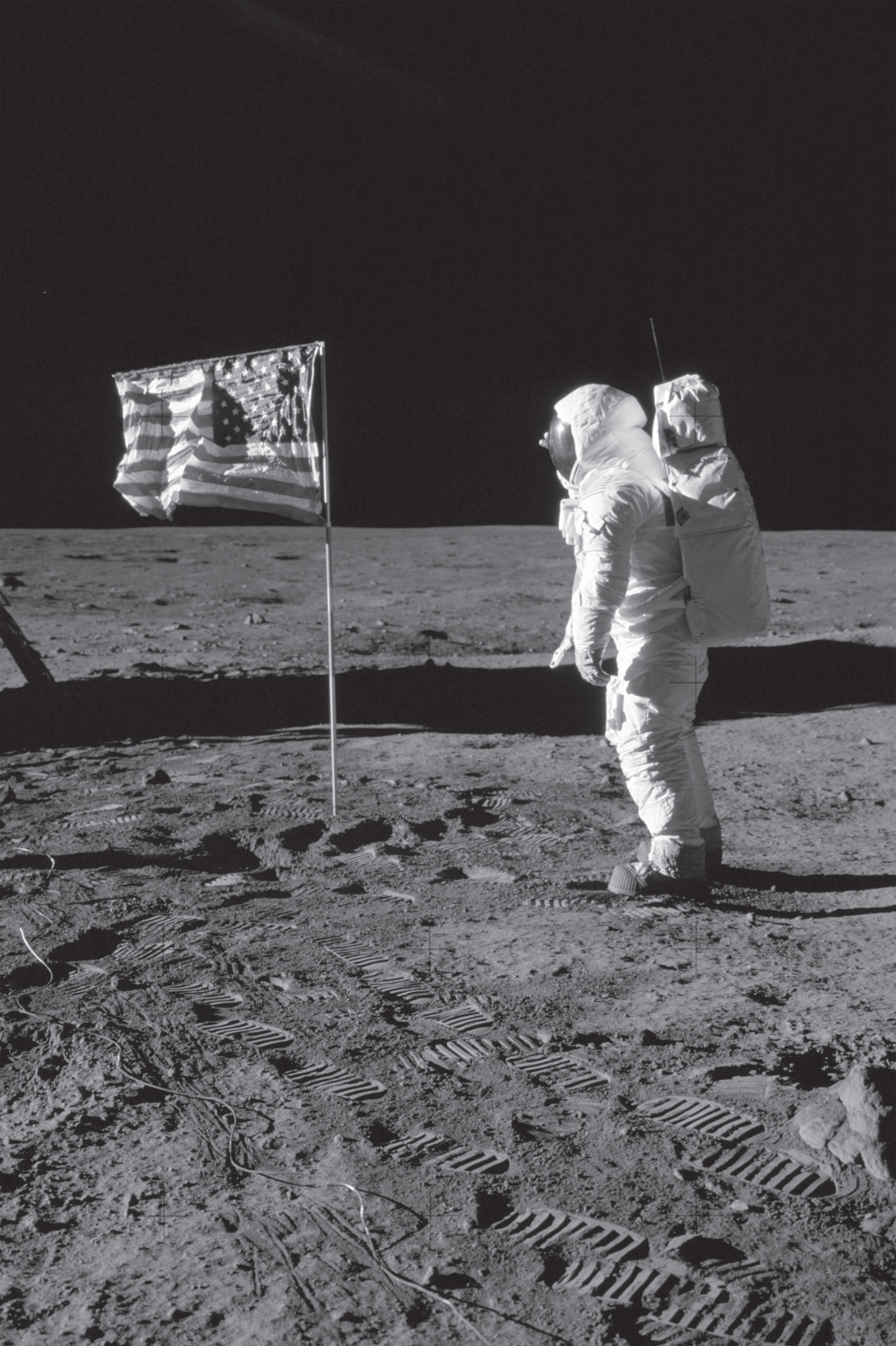

One night when I was five, my parents shook Mark and me awake and led us down to the living room to watch a blurry gray image on TV. They explained we were about to see men walking on the moon. I remember hearing the broken voice of Neil Armstrong and trying to believe that he was really walking on the glowing disk I could see out our window.

When I joined NASAs class of 1996 and started getting to know my astronaut classmates, many of us shared the same memory of coming downstairs in our pajamas as little kids to watch the moon landing. Most of us had decided, then and there, to go to space one day. At that time, we were promised that Americans would land on the surface of Mars by 1975. Anything was possible now that we had put a man on the moon. Then NASA (the National Aeronautics and Space Administration) lost most of its funding after the public lost interest in new Apollo missions, and our dreams of space had to be downgraded.

In the years since, NASA has built the International Space Station (ISS), the hardest engineering feat human beings have ever achieved. Getting to Mars and back will be even harder, and I have spent a year in spacelonger than it would take to get to Marsto help answer some of the questions about how we can survive that journey.

M Y EARLIEST MEMORIES are of the warm summer nights when my mother, Patricia, tried to settle Mark and me to sleep in our house on Mitchell Street in West Orange, New Jersey. It was still light outside, and I could hear the sounds of the neighborhood drifting in through the open windowsolder kids yelling, the thumps of basketballs against driveways, the rustling of breezes high in the trees, the faraway sounds of traffic. I remember the feeling of drifting weightless between summer and sleep.

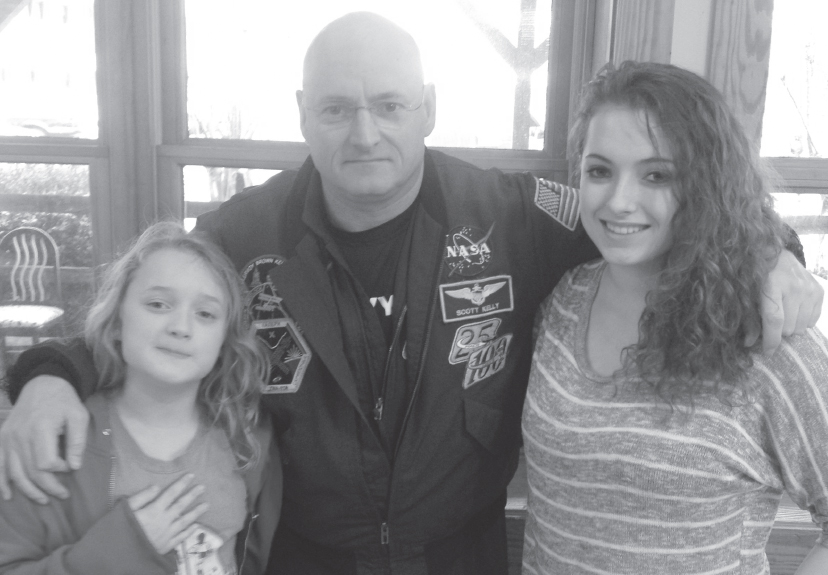

My brother and I were born in 1964. Members of my fathers side of our family lived all up and down our block, aunts and uncles and cousins in both directions. The town was separated by a hill. The more well-off lived up the hill, and we lived down the hill. I remember waking early in the morning with my brother when we were small, maybe two years old. My parents were sleeping, so we were on our own. We got bored, figured out how to open the back door, and left the house to explore, two toddlers wandering the neighborhood. We made our way to a gas station, where we played in the grease until the owner found us. He knew where we lived and stuck us back in the house without waking my parents. When my mother finally got up and came downstairs, she was confused by the grease all over us. Later that day, the owner came over and told her what had happened.

One afternoon when we were in kindergarten, my mother told us she had an important task for us. She held a white envelope in front of her as if it were a special prize. Mom told us to put the letter in a mailbox directly across the street from our house. But first, she warned us that it wasnt safe to cross in the middle of the streetwe could be hit by a car. So we were to walk up to the corner and cross the street there, then walk back to the mailbox on the other side of the street and mail the letter. When our job was done, we needed to take the long way home, walking to the corner to cross again. We promised to follow her instructions.

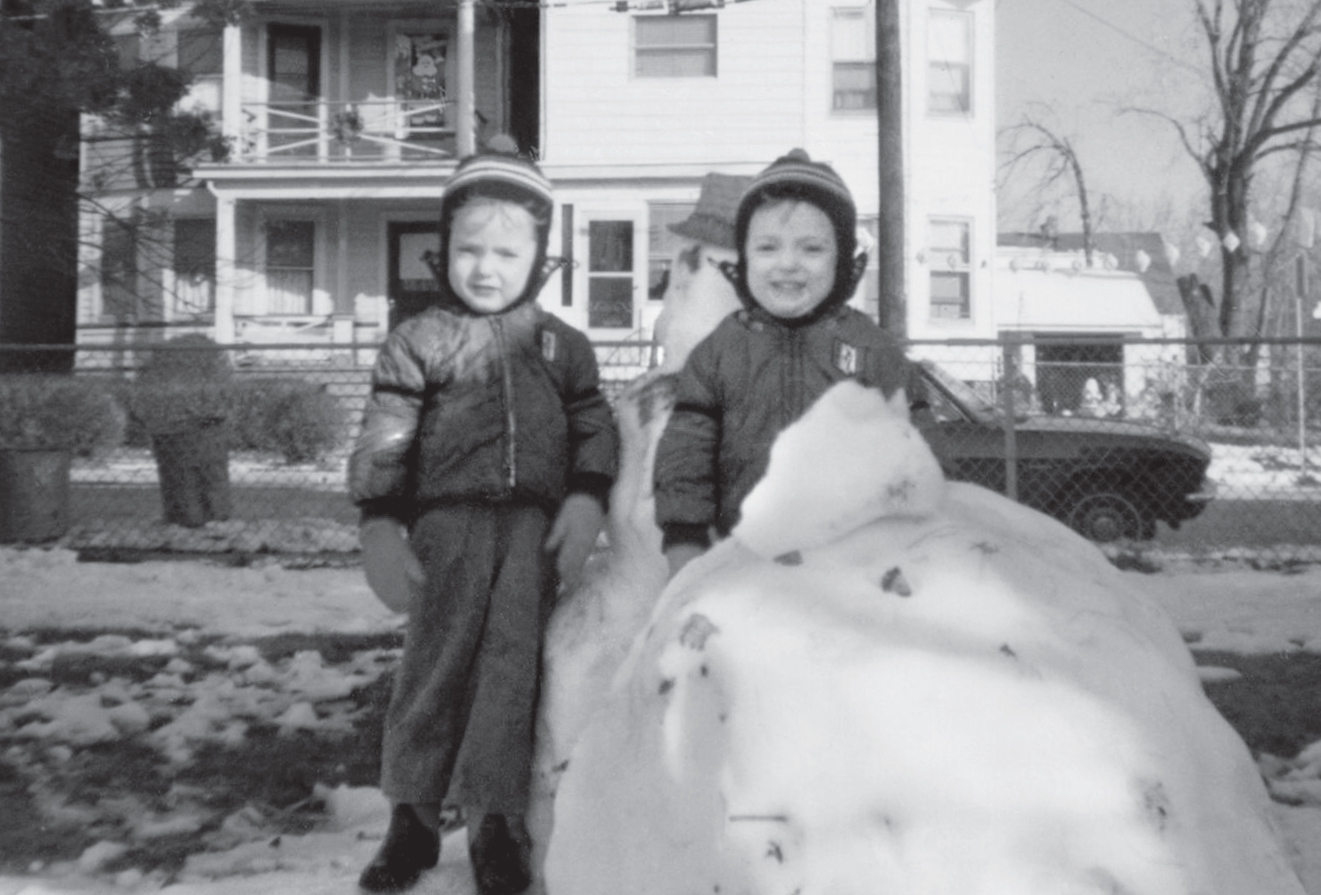

Two future astronauts playing in the New Jersey snow at almost three years old. December 1966.

Mark and I set off and walked up to the corner. We looked both ways, crossed, and made our way to the mailbox. Mark boosted me up to pull down the heavy blue handle, and I proudly deposited the letter in the slot. With our job complete, it was time to head back home.

Im not walking all the way back to the corner, Mark announced. Im just going to cross the street right here.

Mom said we should cross at the corner, I reminded him. Youre going to get hit by a car.

But Mark had made up his mind.

I set off back toward the corner myself, eager to get home and be praised for having followed directions. I reached the corner, crossed, and turned back toward the house. The next thing I heard was car brakes squealing and the thump of a collision. Out of the corner of my eye, I saw something the size and shape of a kid flying up into the air.

Mark sat, dazed, in the middle of the street, while the frantic driver fussed over him. Someone ran for our mother, an ambulance came, and Mark was whisked away to the hospital. I spent the rest of the afternoon and evening with my uncle Joe and his family. I was left at home to worry about my rule-breaking brother, as I was steaming over the unfairness of having to stay home and eat liver for dinner with our uncle while waiting for news about my wounded twin. Mark had a concussion and had a short hospital stay and got lots of attention, while I felt like I got the worse end of the deal.