CONTENTS

Guide

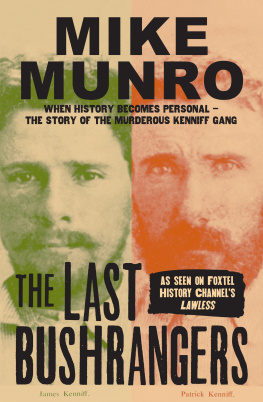

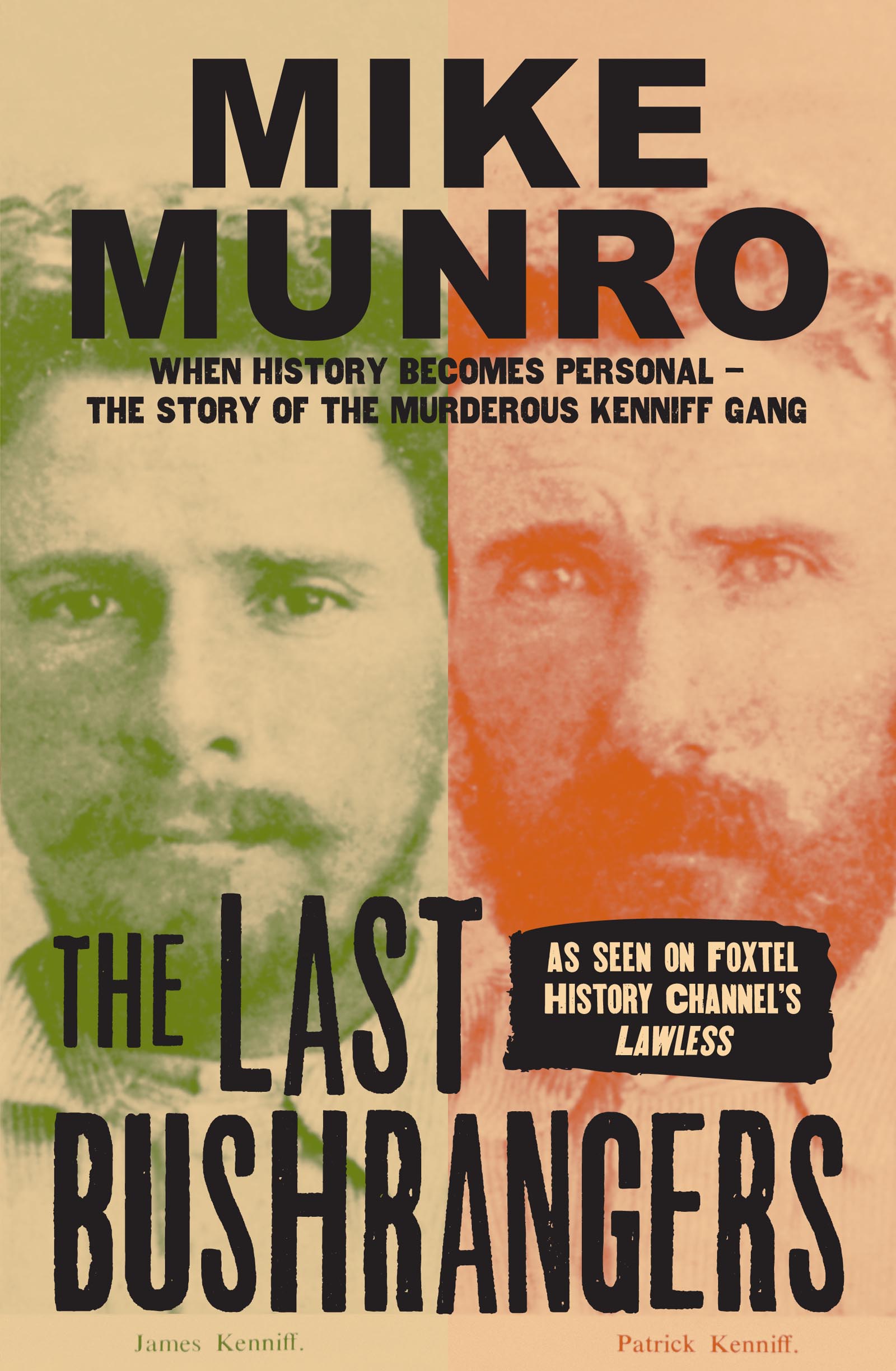

To Constable George Doyle and Albert Dahlke

two decent law-abiding men, whose lives were taken in

such a ghastly manner

CONTENTS

It was obvious that he was dying, although he wasnt really that old only sixty-one. The cirrhosis of the liver had taken its toll, not to mention the cancer ravaging his colon. There were no regrets, no what-could-have-beens, because he wasnt that sort of bloke. He lived for the day, spending what was in his pocket, while tomorrow never entered his thoughts.

The youngest of five children, hed been told by his doting mother that he was special. Most days she got him to hide around the corner until his two sisters and two brothers had gone to school, and then hed sneak back to spend the day with her. So he grew up a spoilt mummys boy, with a derelict work ethic, making and losing quick and easy money, mostly at racetracks. He became a womaniser and a spectacularly lousy husband and father. Had he used his gift of the gab and charismatic personality for the good, he could have done anything even without a proper education. He much preferred the con, though, and the company of racetrack touts, crooked horse trainers and jockeys. He was second-generation Australian, but youd swear hed arrived from Tipperary the day before.

His name was Raymond Michael Munro, and he was my father. And as he lay dying in a Sydney hospice, I realised I hardly knew him. I felt, as his son, that it was my responsibility to be there for him at the end. He had already spent several months at our family home undergoing treatment, but it was more an expected duty on my part than a sincere need to look after him. He had no one else in the world. Gone were the jet-black hair and the twinkle in his blue eyes. Gone too were the bravado and the jokes that I think shielded his insecurities. He was heavily drugged with painkillers so his speech was slurred. It was a sad and lonely end. I wanted to ask him if he regretted anything but we just werent that close.

My mother, Beryl, had been deeply in love with Mick, as my father was always called, and for the first glorious and irresponsible years of their marriage she had revelled in his fast and easy way of life. But by the time I was three she was fed up with irate husbands banging on her front door, trying to find my father so they could threaten him to stay away from their wives. Mum was also sick of policemen turning up, wanting to question him over yet another petty con. She was left with the choice of trying to rehabilitate her charming no-hoper husband or saving her young son from Micks unpredictable and increasingly erratic influence.

She chose me. One day she simply packed up and walked out of our rented home in Sydneys southern suburbs and went north, over the Harbour Bridge, to affluent Mosman, where she became a housekeeper in a monastery of twelve Marist brothers.

I was four when we arrived at the Marist community, and would spend almost ten years there, rarely seeing my father. Mum and I were allocated two tiny rooms at one end of the complex, which bordered a school yard and classroom buildings. There was barely enough space for a bed in one room and a table and two chairs in the other tiny room. I had to sleep with Mum until I was thirteen, when she could afford to buy a second bed, which doubled as a divan during the day. There was also a minuscule bathroom with just enough room for a toilet and shower.

The endless work of cleaning, washing clothes and cooking thirty-six meals a day eventually took their toll on Mum. In the process of giving me a chance for the future, she had utterly ruined any chance for herself. During the years my parents were together, and in the years before they met, my mother rarely drank alcohol. In one of only two photos I have of Mum and Mick together, she can be seen drinking what looks like water while the other people at the table are clearly drinking wine or beer. But the long hours at the monastery, combined with desperate loneliness, turned the confirmed teetotaller into a chronic alcoholic. By the time I was five, Mum was starting her tortuous journey to becoming an afterhours closet drinker. By the time I was six, she was well on her way to becoming a tormented gold-plated alcoholic.

It was during the blur of alcoholism that her tongue loosened, and the first hint of my fathers family scandal spilled over into her almost-constant verbal abuse of me. I became the target of all her frustrations and resentments over her lost love and her station in life as a housekeeper. Youre from a family of thieves and murderers anyway, shed scream at me. But she would often mix it up with pearlers like: Youre just like your father; youll never amount to anything. Youre nothing but a pasty-faced nothing. So being from a family of thieves and murderers had no meaning whatsoever for me. It was just another form of drunken abuse that I became used to hearing. I heard it over and over again throughout my childhood, teenage years and even into adulthood. For half my life I put it down to Mums unhappiness in losing the one and only man shed ever loved. It was as if she couldnt bear to ever set eyes on him again but, at the same time, would never get over him.

Mums situation was made even more tragic because, when sober, she was a well-read woman with a great sense of humour and an incredible work ethic albeit very little affection for me. So I grew up with this Jekyll and Hyde character, and tried to tell myself that whatever she said was only the grog talking.

Meanwhile, the verbal abuse escalated into physical violence. Id cop beltings with the plug of the iron and the buckles of belts, all the while being told I was from a family of mutilators and bushrangers on Micks side, of course. Still it meant nothing; it was just another form of namecalling. I became immune to it and never questioned the meaning behind it. So the secret stayed hidden... until I sat beside my fathers deathbed.

I was in my late twenties when the mortally ill Mick announced he needed to tell me a terrible family secret. I blanched, because if wild Mick described it as terrible, I thought it must really be catastrophic. Then I wondered whether my father meant to reveal the existence of children from his numerous extramarital affairs. (Although my parents only saw each other three times after Mum left Mick, they never divorced. My shameless father told his many girlfriends that his wife and son had been killed in a car accident.) But Mick went on to say that he felt he was at last able to tell me his secret because he had only one sibling left alive his older brother John, whod spent his entire adult life at racetracks as a professional gambler and couldnt care less about the family secret being revealed. Mick and Jack, as his brother was invariably called, were definitely the black sheep of the family. Their doctrine had always been: Dont grass on anyone for any reason and, above all, dont ever become a copper. So was the secret something to do with Micks brothers and sisters? I was confused, and worried all over again.

But the moment Mick began to disclose the secret the family had kept hidden for so long, his face lit up with excitement. I immediately thought it couldnt be that serious because he looked so passionate about it. What I didnt realise was that, to Mick, the sorry story he was about to tell me was something of which to be proud.

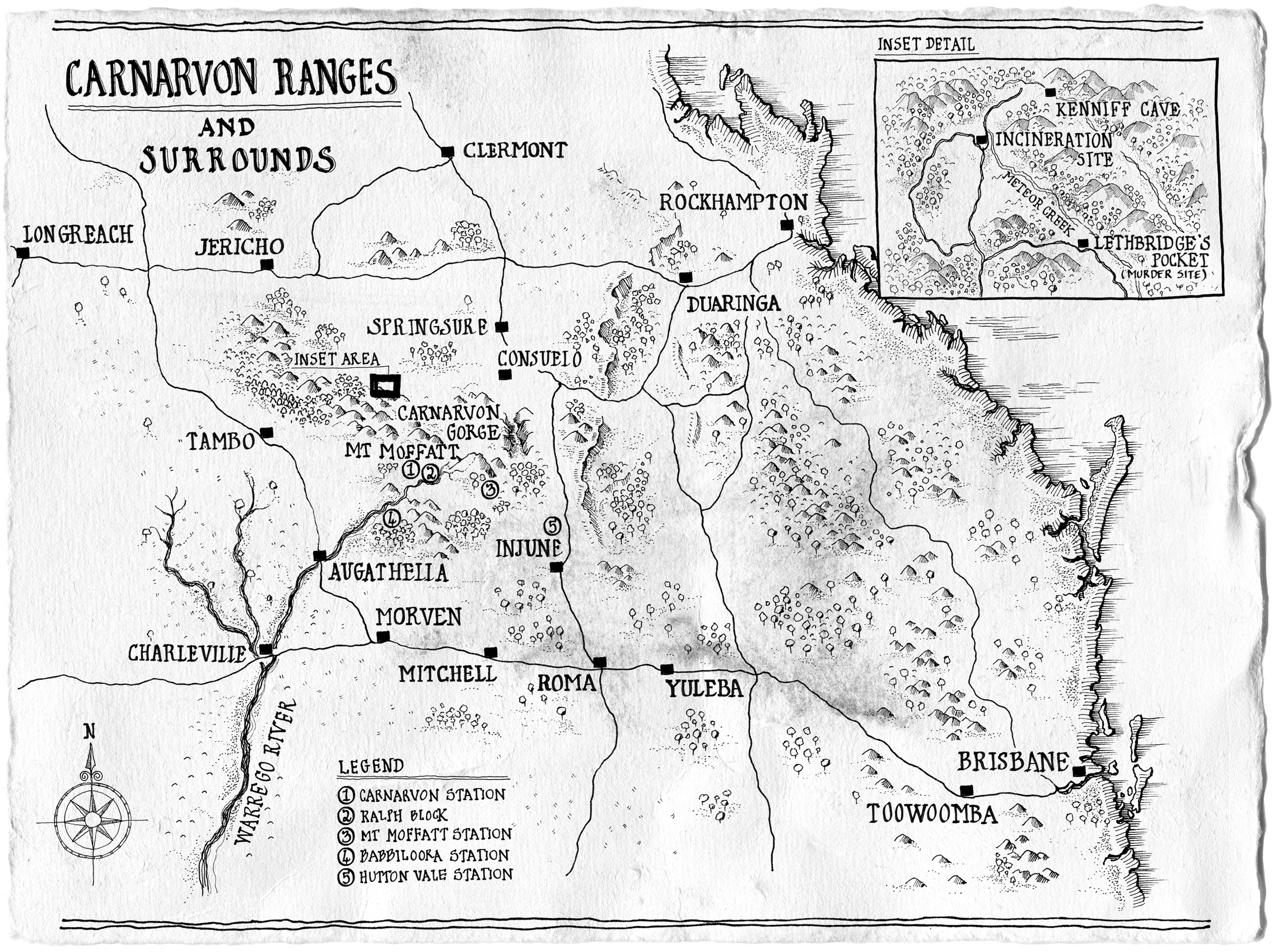

Your great-uncles, he boasted, were convicted of murdering a policeman and a station manager, cutting their bodies up, incinerating them and leaving the leftover flesh and bones in police saddlebags for the cops to find.

Next page