Copyright 2011 by Paul Trynka

All rights reserved. Except as permitted under the U.S. Copyright Act of 1976, no part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Little, Brown and Company

Hachette Book Group

237 Park Avenue

New York, NY 10017

Visit our website at www.HachetteBookGroup.com

www.twitter.com/littlebrown

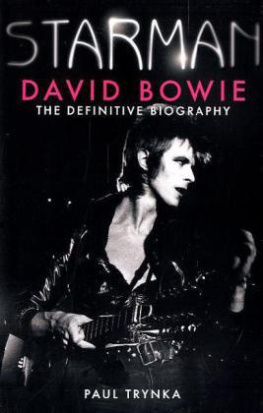

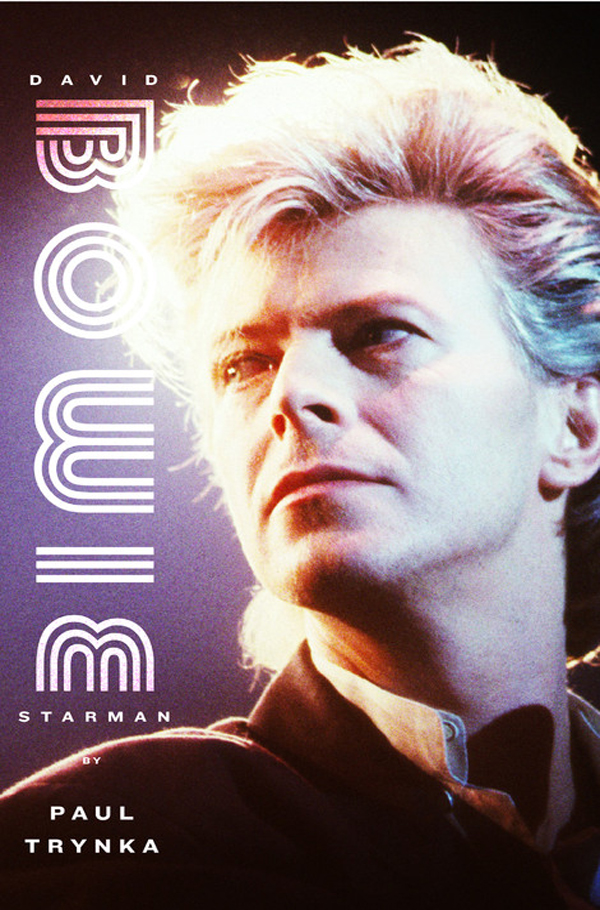

Jacket design by Allison J. Warner

Front jacket photograph Catherine Cabrol / Kipa / Corbis

First eBook Edition: July 2011

Little, Brown and Company is a division of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

The Little, Brown name and logo are trademarks of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

ISBN: 978-0-316-13424-8

Iggy Pop: Open Up and Bleed

Denim (with Graham Marsh)

Portrait of the Blues

To Kazimierz and Maureen: heroes

Thursday evening, seven oclock; decadence is about to arrive in five million living rooms. Neatly suited dads are leaning back in the comfiest chairs, mums in their aprons are clearing away the dishes, and the kids, still in school shirts and trousers, are clustered around TVs for their most sacred weekly ritual.

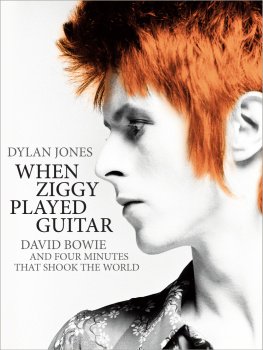

The members of the tiny studio audience, milling around in tank tops and dresses, clap politely as he strums out two minor chords on his blue twelve-string guitar. The camera cuts from his hands to his face, catching the barest hint of a smirk, like a child hoping to get away with something naughty. But then as his friends Trevor, Woody, and Mick Ronson clatter into action with a rollicking drumroll and throaty guitar, the camera pulls back and David Bowie meets its gaze unflinchingly. His look is lascivious, amused; as an audience of excited teens and outraged parents struggle to take in the quilted multicolored jumpsuit, the luxuriant carrottop hairdo, the spiky teeth, and those sparkling, mascaraed come-to-bed eyes, he sings us through an arresting succession of images: radios, aliens, get-it-on rock n roll. The audience is still grappling with this bizarre spectacle as a staccato guitar rings out a Morse code warning and then, all too suddenly, were into the chorus.

From the disturbingly new, we shift to the reassuringly familiar; as he croons out Theres a starman, his voice leaps up an octave. Its an ancient Tin Pan Alley songwriters trick, signaling a release, a climax, and as we hear of the friendly alien waiting in the sky, the audience suddenly recognizes a tune, and a message, lifted openly, outrageously, from Over the Rainbow, Judy Garlands escapist, Technicolor wartime anthem. Its simple, sing-along, comforting territory and lasts just four bars before David Bowie makes his bid for immortality, less than sixty seconds after his face appeared on Top of the Pops, the BBCs family-friendly music program. He lifts his slim, elegant hand to the side of his face as the platinum-haired Mick Ronson joins him at the microphonethen casually, elegantly, he places his arm around the guitarists neck and pulls him lovingly toward him. Theres the same octave leap as he sings starman againthis time, it doesnt suggest escaping the bounds of Earth; it symbolizes escaping the bounds of sexuality.

The fifteen-million-strong audience struggles to absorb this exotic, pansexual creature; in countless households, the kids are entranced in their thousands as parents sneer, shout, or walk out of the room. But even as the kids wonder how to react, theres another stylistic swerve; with the words let the children boogie, David Bowie and the Spiders break into an unashamed T. Rex boogie rhythm. For thousands of teenagers, there was no hesitation; those ninety seconds on a sunny early evening in September 1972 would change the course of their lives. Up to this point, pop music had been mainly about belonging, about identification with their peers. This music, carefully choreographed in a dank basement under a South London escort agency, was a spectacle of not-belonging. For scattered isolated kids around the UK, and soon on the American East Coast, and then on the West Coast, this was their day. The day of the outsider.

I N the weeks that followed, it became obvious that these three minutes had put a rocket under the career of a man all too recently tagged as a one-hit wonder. Most people who knew him were delighted, but there were hints of suspicion. Hip Vera Lynn, one cynical friend called it in a pointed reference to The White Cliffs of Dover, the huge wartime hit that had also ripped off Judy Garlands best-known song; this was too knowing. A few weeks later, to emphasize the point, David started singing somewhere over the rainbow over the Starman chorusas if to prove Pablo Picassos maxim that talent borrows, genius steals.

And steal he hadwith a clear-eyed effrontery as shocking as the lifted melodies. The way he collaged several old tunes into a new song was a musical tradition as old as the hills, one still maintained by Davids old-school showbiz friends, like Lionel Bart, the Oliver! writer and musical kleptomaniac. Yet showing the joins brazenly, like the elevator shafts of the Pompidou Centre or the stock photos appropriated by Andy Warhol, was a new trick, a postmodernism that was just as unsettling as the postsexualism Bowie had shown off with that arm lovingly curled over Mick Ronsons shoulder. Rock and roll was a visceral medium, born out of the joy and anguish sculpted into the first electric blues in the turmoil of postwar America. Was it now just an art game? Was the carrot-haired Ziggy, potent symbol of otherness, just an intellectual pose?

When David Bowie made his mark so elegantly, so extravagantly, that night on Top of the Pops in a thrilling performance that set the seventies as a decade distinct from the sixties, every one of those contradictions was obviousin fact, they added a delicious tension. In the following months and yearsas he dumped the band that had shaped his music; when his much-touted influence Iggy Pop, the man whod inspired Ziggy, dismissed him as a fuckin carrot-top who had exploited and then sabotaged him; when David himself publicly moaned that his gay persona had damaged his career in the United Statesthose contradictions became more obvious still.

So was David Bowie truly an outsider, or was he a showbiz pro exploiting outsiders, like a psychic vampire? Was he really a starman, or was it all cheap music-hall tinsel and glitter? Was he gay, or was it all a mask? There was evidence aplenty for both. And that evidence accumulated as his career continued, as fans witnessed, wide-mouthed, momentous shows like his wired, fractured appearance on Dick Cavett and his twitchy but charming camaraderie on Soul Train. How much of this bizarre behavior was a performance, a carefully choreographed sequence?

In the subsequent years, David Bowie, and those around him, would struggle to answer this question. Hed emerged from a showbiz tradition propelled by youthful ambition, his main talent that of repositioning the brand, as one friend put it; that calculation, that executive ability, as Iggy Pop described it, marked him as the very antithesis of instinctive rock-and-roll heroes like Elvis Presley. Yet the actions that signaled the death of rock and roll announced a rebirth too. Maybe this wasnt rock and roll like Elvis had made rock and roll, but it led the way to where rock and roll would go. Successors like Prince and Madonna, Bono and Lady Gagaeach seized on repositioning the brand as a set-piece example of how to avoid artistic culs-de-sac like the one that had imprisoned Elvis. For Bowie himself, though, each brand renewal, each metamorphosis, would come at a cost.