Copyright 2015 by Pamela Katz

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Nan A. Talese / Doubleday, a division of Random House LLC, New York, and in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto, Penguin Random House companies.

www.nanatalese.com

DOUBLEDAY is a registered trademark of Random House LLC.

Nan A. Talese and the colophon are trademarks of Random House LLC.

Permission acknowledgments can be found on .

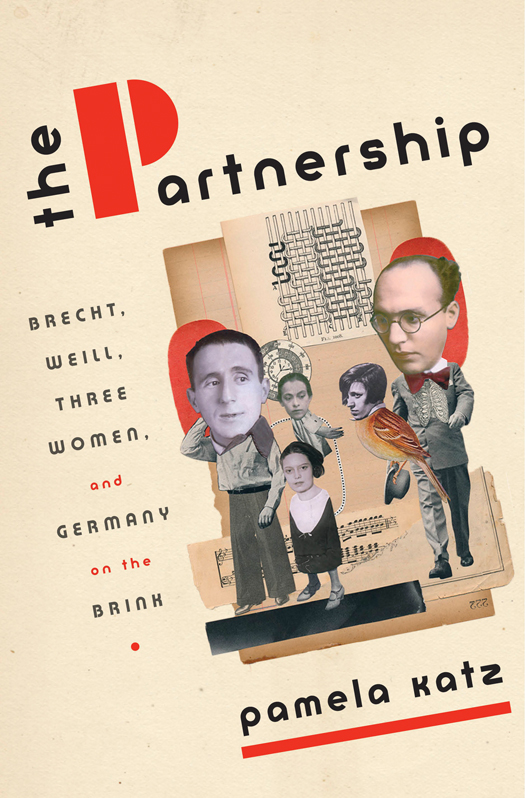

Jacket design by John Fontana

Jacket collage illustration by Marty Blake

Portraits: (left to right, top to bottom) Bertolt Brecht, c. 1930s Bettmann / Corbis; Helene Weigel, Akademie der Knste, Berlin, Bertolt-Brecht-Archiv FA 17/003, Foto: Osborne, Li / Zander & Labisch; Lotte Lenya, courtesy of the Weill-Lenya Research Center, Kurt Weill Foundation for Music, New York; Kurt Weill, c. 1930s. akg-images; Elisabeth Hauptmann, 1930. ullstein bild / The Granger Collection, NYC.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Katz, Pamela.

The partnership : Brecht, Weill, three women, and Germany on the brink / by Pamela Katz.

pages cm

ISBN 978-0-385-53491-8 (hardcover) ISBN 978-0-385-53492-5 (eBook)

1. Weill, Kurt, 19001950. 2. Brecht, Bertolt, 18981956. 3. Weill,

Kurt, 19001950Relations with women. 4. Brecht, Bertolt,

18981956Relations with women. 5. ComposersBiography.

6. Authors, German20th centuryBiography. 7. Dramatists,

German20th centuryBiography. I. Title.

ML 410. W 395 K 38 2015

782.1092dc23

[ B ] 2014017458

v3.1

To Florian, Rebecca, and Louisa

Contents

CHAPTER 1

The First Encounter

A man of precise habits, Kurt Weill always emerged early from behind the heavy piece of tapestry that divided the studio apartment in Berlin where he slept and worked. For a musical prodigy, he had conspicuously small ears, especially in comparison to the large dark eyes that dominated his face and were bursting with intelligence and warmth through his thick, wire-rimmed glasses. Wearing his perfectly ironed trousers and shirt, he sat down at eight in the morning and worked ceaselessly until late in the afternoon. He composed quietly. The large piano that filled most of the working half of his studio wasnt touched until he had heard the finished music in his head. Friends joked that he only used the elegant black instrument as a place to put his pipes. Weills handwriting was immaculate, and he rarely changed a note once it had been written. With a perfectionists rigor, he slowly and calmly captured, in his words, the roaring hymns of the stars. He was writing music the likes of which no one had ever heard before.

The twenty-seven-year-old composer had already impressed many of the cultural giants of his day, but that hardly satisfied the ambitious Weill. It wasnt enough to simply shake up the old institutions; he wanted to transform them by writing music that appealed not only to the intelligence but also to the hearts and hips of a large audience. He dreamed of hearing his songs in the whistle of a taxi driver.

And he was a man who expected his dreams to come true, at least when it came to music.

On March 24, 1927, the nature-loving Weill probably would have been delighted by the unusually warm breeze coming in through the open window. He always reveled in the approach of spring, and that year it was arriving astoundingly early. It had been nearly seventy degrees the day before, a cause for celebration in the cold northern city of Berlin, but too warm for the butter he usually kept outside on the wide stone windowsill in winter. Before the rampant inflation had ended three years earlier, such commodities had been far more valuable than the ever-shifting currency. Weill had often calculated the price of his composition lessons in grams of butter.

On this particular day, he was excited to meet a writer whod caught his attention and was eager to be finished with his work. Weill pursued literary talent with the determination of a hunter in the wild, and although the furnishings of his tiny room didnt belong to him, the dark ugly pictures of hunting dogs that adorned the walls seemed appropriate to his voracious artistic appetite. I need poetry to set my imagination in motion; and my imagination is not a bird, its an airplane, Weill wrote his brother when he was only nineteen years old. Hed been on the quest ever since.

Before taking leave of his desk, Weill wrote a quick letter to his wife, who was out of town. Letter-writing was another of his devoutly observed rituals. In addition to maintaining a regular correspondence with a variety of friends and colleagues, he wrote almost daily to his brother, his publisher, and, when she wasnt at home, his wife. Letters punctuated his life every bit as much as musical notes, and he relished describing the details of his day to the love of his life, the savvy, sensual woman who had shocked his family, Lotte Lenya. Last night I worked here until one oclock, while outside the incessant demonstrations paraded by, he wrote. That was something to warm my revolutionary heart. Today again Ive been sitting at my desk since eight this morning now I have to go see B. Addio! Be loved, Schwmmi (Little Mushroom). Kaisers personal and professional friendship, which Weill had earned by brazenly approaching him at the age of twenty-four to collaborate on an opera project, was the strongest proof that the composer had conquered the literary elite. But such success didnt diminish his urgent desire for his music to engage the attention of Herr Hassforth and the other carpenters and electricians with whom he shared an address.

No one looking at Weill, a small, prematurely balding young man wearing conservative clothes and schoolboy spectacles, would believe that he had a revolutionary bone in his body. But judging the composer by his appearance would be a mistake. His calm exterior was there to protect the creativity that exploded within him. He had the talent and skill to compose an entirely new kind of music and he worked toward this goal every day without fail. He was a revolutionary artist in the precise sense of the word; he was changing what had come before. But his working methods were grounded in the conservative, even Prussian, traditions of punctuality, discipline, and rigor.

Crossing the inner courtyard and going through the dark hallway to the massive front door, the light would momentarily blind him before he could focus on the regal Schloss Charlottenburg across the street. Surrounded by its landscaped grounds, the palace instantly recalled the royalty that once ruled the land. It had only been eight years since Kaiser Wilhelm had abdicated and it would take some time before the stench, and the opulence, of the monarchy would entirely disappear.

In fact, the demonstrations Weill mentioned in his letter had been to rally support for a proposed law to confiscate all of the aristocratic properties in order to benefit the unemployed and the disabled veterans, both victims of the countrys financial collapse.Weill had suffered along with millions of other Germans. At the very least, everyone could take comfort in the fact that there hadnt been an armed uprising or political assassination in several years. When the citizens of Berlin peacefully demonstrated about the redistribution of wealth, it was considered a relatively docile event in the still-fragile Weimar Republic.