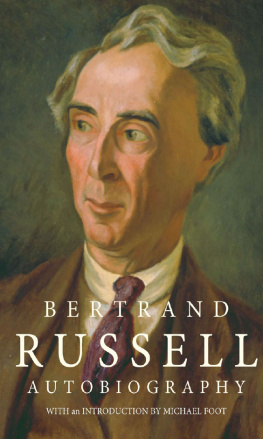

Ronald Clark

The Life of Bertrand Russell

Contents

Preface

Men and women will be writing about Bertrand Russell as long after his death as they have been writing about Leonardo or Napoleon. His impact on twentieth-century philosophy will be a subject for continuing discussion, and so will the more specific interactions between Russell and Wittgenstein. The effect on the pacifism of the inter-war years of his work for the No-Conscription Fellowship is already being studied. The passage of time will eventually give perspective to the nuclear debate of the post-war decades, and may well provide even more justification for Russells changes of stance than can be found today. Much the same may well emerge about what has been called his preventive-war phase. Russells letters to Lucy Donnelly, to Lady Constance Malleson and above all to Lady Ottoline Morrell will, when published in full, reveal the deep emotional complexities of a man for whom no venture was too dangerous, no exploration too unlikely. It will eventually, also, be possible to describe in greater detail some aspects of Russells later life although it now seems conclusive at least to the present writer that these details will not materially alter the picture it is possible to draw today.

All these specialist aspects of one life are different facets of the intellectual diamond which scintillates in the huge quarry of the Bertrand Russell Archives at McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario. This is the quintessential man, the bundle of contradictions passionately dedicated to intellect, at times carrying the rational argument to irrational extremes; the natural-born emotional adventurer for ever hampered by orphaned youth and too early marriage. This Russell in the round is greater than the sum of his constituent parts, a man of epic proportions, struggling through a lifetime beset with frustration and near-disaster; in youth the constitutional sceptic, in old age the sometimes splendid figure with courage never to submit or yield.

RONALD W. CLARK

Marlborough, December 1974

The influence of Bertrand Russell does not spring solely from his intellect, a weapon honed razor-sharp and wielded with impartial relish against both foe and friend. A life-span that only just missed its century also helped; so did ancestry, and so did the genuinely if unexpectedly romantic reasons for which he sometimes marched into battle.

When he was born, the old Queen still had three decades to lord it over palm and pine; when he died, men had walked on the moon. When he was young, men still searched with disinterested delight for the logical heart of mathematics; before he died it had been found and had helped to spawn the computer industry. Thus Russell links General Grants presidency with Nixons reign, the Zulu wars with the ground-swell of nuclear conscience that floods across frontiers, the vestigial remnants of late nineteenth-century optimism with the dark terror of the times.

This spread of life across four generations provided burden as well as benefit. In education, it is true, his innovations became everyday usage long before his death. To the sexual relationship, a subject never far from intellect or passion, his crusading fervour justified for the masses a freedom previously available only on his own aristocratic and intellectual stamping-grounds. In the politics of peace his record is more contradictory than he would wish and perhaps more successful than his enemies would admit: Pugwash, that little-known international omen of hope which he encouraged into existence, and whose influence surpassed that of C.N.D. of which he became a symbol, may yet be seen to have helped turn men away from the third world war. But in mathematics, where he sought than man, he was eventually to find sappers working successfully beneath the proud edifice he built. In philosophy he lived long enough to see his revolutionary ideas first abused, then accepted, then become part of history and, as such, vulnerable to dissection and revision. But his spirit survived, buoyed up with an optimism which owed nothing to hope of a next world, unqualified by the wrath to come. After all, he was a Russell.

His long life was begun in a tradition which took it for granted that a man would make his mark on history. On both sides his predecessors had been born to rule, not as a right but a duty, and his radical instincts were based on confidence that to the aristocrat all things are possible. His mother, Kate Stanley, was descended from the French invaders who had landed in 1066, and whose successors had been granted the pourboire of an earldom for good work on Bosworth Field. His father, Lord Amberley, son of the 1st Earl Russell who had fought the Reform Bill through Parliament and survived to become Victorias voice from the past, had been given a comparable though more picturesque background by J. H. Wiffen, librarian to the 1st Earls father, the 6th Duke of Bedford. Writing the history of the Russells for the duke, Wiffen pressed back regardless, unhampered by mere facts, and unearthed an ancestor who had not only landed, as it were, side by side with the Stanleys near Hastings, but who could claim a link with Olaf the Sharp-eyed, a warrior for whom the dutiful Wiffen found a connection with Scandinavian royalty. In due course of begetting, Olaf produced William, Baron of Briquebec, the first that took the name of Bertrand. The Barons son, Hugh Bertrand, crossed the Channel in 1066 and, vide Wiffen, the Russells were on their way.

Little of this story was needed. The family could in fact trace a long and distinguished line back to its financial foundation with a plump grant of abbey lands in Tudor times. One incumbent, William, Lord Russell, was executed for alleged complicity in the Rye-House Plot. But, on orders, his chaplain wrote the life of Julian the Apostate which outspokenly argued that resistance to authority may be justified, a belief much favoured by many of the victims descendants. The accession of William and Mary brought exculpation and a parliamentary bill which claimed that Lord Russell had been wrongly condemned. There was, moreover, family recompense for the miscarriage of justice. The earldom was stepped up to a dukedom. The Stanley Sans Changer on their arms might contrast strangely with the Russell Che Sara Sara, the austere without changing with the happy-go-lucky hedonism of whatever will be, will be; but in mutual self-confidence they were not divided. To Russell, as to all practising members of both families, the fences were there to be taken.

The traditional attitudes had their penalties as certainly as length of life. Leadership demanded that the emotions be kept discreetly from the public gaze. In the world of Russell and his ilk, one did not wince nor cry aloud, a strait-jacketing of the feelings compounded in his case by an intellect which created its own difficulties and traumas. Thus in most of his writings, for most of his friends, an essentially romantic approach to subjects as different as mathematics and the Russian Revolution, the problems of pacifism and of the passions, was concealed by cerebral sparkle. In such circumstances any man might appear more cold-blooded and clinical than he really was. For Russell, whose battened-down youth was followed by buttoned-up marriage, two ghosts which gibbered over his shoulder down the years, much emotion demanded much concealment.

Lord Amberley, who suffered from Lord Johns fame as much as Russells own children were to suffer from his, married Kate Stanley on 8 November 1864. He was twenty-one, his wife a few months older. An heir to the title, John Francis Stanley, later known as Frank, was born on 12 August 1865 in, as he put it in his autobiography, strict accordance with of family duty. Two years later Amberley stood for Nottingham and entered politics. The following year he left them, being unsuccessful in the General Election of 1868 despite the efforts of his cousin, the Duke of Bedford, who paid all expenses. Support for birth-control had proved enough to remove any chance of a political career.

Next page