Contents

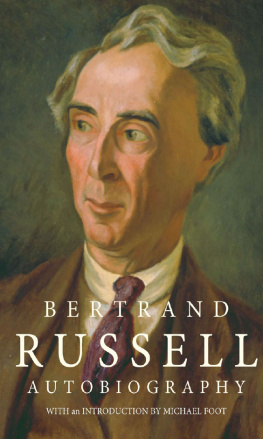

Russell, the Militant Philosopher

Everyone has heard of Bertrand Russell. He was a great thinker, an agitator imprisoned for his beliefs, and a man who changed Western philosophy for ever. He was a profound sceptic who refused to take anything for granted and protested all his life against the senseless slaughter of the First World War, against the evils of all kinds of totalitarian dictatorship, and against nuclear weapons which he thought would eventually destroy us all. He wrote on a huge range of subjects and his work has influenced large numbers of people from stuffy academics to scruffy anarchists.

I F A MAJORITY IN EVERY CIVILIZED COUNTRY SO DESIRED, WE COULD, WITHIN 20 YEARS, ABOLISH ALL ABJECT POVERTY, QUITE HALF THE ILLNESS IN THE WORLD, THE WHOLE ECONOMIC SLAVERY WHICH BINDS DOWN NINE TENTHS OF OUR POPULATION; WE COULD FILL THE WORLD WITH BEAUTY AND JOY, AND SECURE THE REIGN OF UNIVERSAL PEACE.

Russells Upbringing

Bertrand Russell was born in 1872 into a famous and wealthy English aristocratic family. His father was Viscount Amberley and his grandfather was the retired Prime Minister, Lord John Russell. Englands most famous philosopher at that time, John Stuart Mill (180673), was his agnostic Godfather. His parents were radical supporters of the Liberal Party and both advocated votes for women. They were shadowy figures in his life because his mother died of diphtheria when he was two and his father of bronchitis shortly afterwards. His main memories of childhood were of his grandmother, Lady Russell, and the oppressive atmosphere in her house Pembroke Lodge in Richmond Park.

SHE WAS A RESOLUTE PRESBYTERIAN AND A VERY VICTORIAN GUARDIAN. I HAVE FIRM IDEAS ABOUT THE UPBRINGING OF CHILDREN. HER NICKNAME WAS DEADLY NIGHTSHADE.

Bertie and his elder brother Frank were rigorously educated to be upstanding young gentlemen with a strong sense of religious and social duty. Neither boy was encouraged to think or talk about his dead, radical parents. Lady Russell also insisted that both boys receive regular lectures on personal conduct and avoid all talk of sexuality and bodily functions. Frank finally rebelled against his grandmother, but Bertie simulated obedience and, as a result, became a rather isolated, lonely and inauthentic child, acting out his grandmothers image of the perfectly obedient angel.

THE MOST VIVID PART OF MY EXISTENCE WAS SOLITARY THROUGHOUT MY CHILDHOOD I HAD AN INCREASING SENSE OF LONELINESS. I SELDOM MENTIONED MY MORE SERIOUS THOUGHTS TO OTHERS, AND WHEN I DID I REGRETTED IT. IT BECAME SECOND NATURE TO ME TO THINK THAT WHATEVER I WAS DOING HAD BETTER BE KEPT TO MYSELF.

Fear of Madness

It was a feeling of alienation that Russell found hard to shake off. He often felt like a ghost unreal and insubstantial compared to other people. He had nightmares of being trapped behind a pane of glass, excluded for ever from the rest of the human race. He was also terrified of going mad. His uncle Willy was incarcerated in an asylum (for murdering a tramp in a workhouse infirmary) and his maiden Aunt Agatha was mentally unstable.

MY GRANDMOTHER TOLD ME IT WOULD BE UNWISE FOR YOU TO HAVE ANY CHILDREN, AS THEY WOULD ALSO PROBABLY BE DERANGED.

Many of Russells friends and colleagues found him wonderfully amusing and compelling, but also strangely lacking in human warmth. His early days in Pembroke Lodge may have had a negative influence on his ability to relate to others, as well as explaining his powerful feelings of isolation.

The Geometry Lesson

Russell was educated privately by a series of often bizarre and eccentric tutors. (One did experiments on imprinting baby chickens, which consequently followed him all around the house.) Frank decided that it was time to teach his 11-year-old brother some geometry. It was a formative experience for Russell.

HE FELL IN LOVE HE WAS ASTONISHED TO SEE HOW EUCLID COULD DEMONSTRATE AND THEN PROVE HIS WHOLE SYSTEM OF SPATIAL GEOMETRY. I HAD NOT IMAGINED THAT THERE WAS ANYTHING SO DELICIOUS IN THE WORLD

A Pure and Perfect World

It certainly looks as if Russells brain was uniquely wired up for mathematical reasoning from an early age. But there was a problem. Like all knowledge systems, Euclidean geometry begins with a few axioms statements that you just have to accept as true. (A straight line is the shortest distance between two points. All right angles are equal to one another.) The pragmatic Frank explained that it is impossible to generate a body of certain knowledge out of thin air. You have to start somewhere. But young Bertie had deep reservations.

HE WANTED GEOMETRY TO BE BEAUTIFULLY PERFECT AND TOTALLY TRUE. PERHAPS THERE IS A WAY OF PROVING THE FOUNDATIONS OF GEOMETRY?

Mathematics offered Russell a pure and perfect world into which he could escape a world that he spent much of his early life attempting to make even more perfect and true than it already was. Then, one of his well-informed private tutors told Russell of the existence of newly discovered alternative non-Euclidean geometries.

T HESE ALSO WORK PERFECTLY WELL, EVEN THOUGH THEY ARE BASED ON WHOLLY DIFFERENT SETS OF AXIOMS .

T HE UNIVERSE, AND THE SPACE OF WHICH IT IS MADE, IS NOT NECESSARILY E UCLIDEAN .

So perhaps the young Bertie had been right to withhold his assent to Euclidean geometry after all.

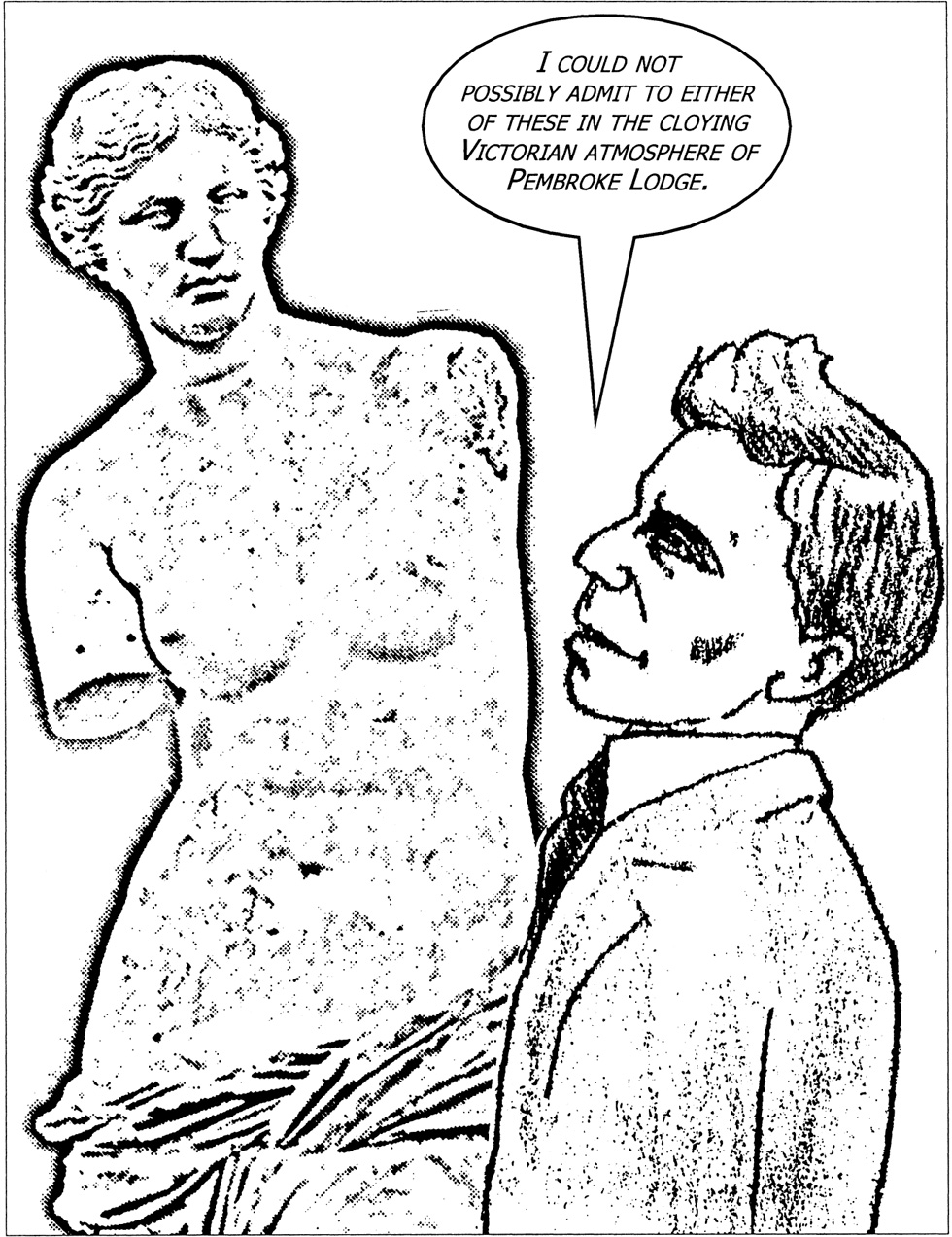

The Quest For Reason

Russell subsequently came to believe that reason was the best way to solve all sorts of problems, not just mathematical ones. It was a view that he held for the rest of his life. He soon came to realize that the people he knew (his grandmother especially) maintained all sorts of beliefs that they could not justify. Russell soon began to have severe doubts about his own religious beliefs, and to experience feelings of sexual desire.