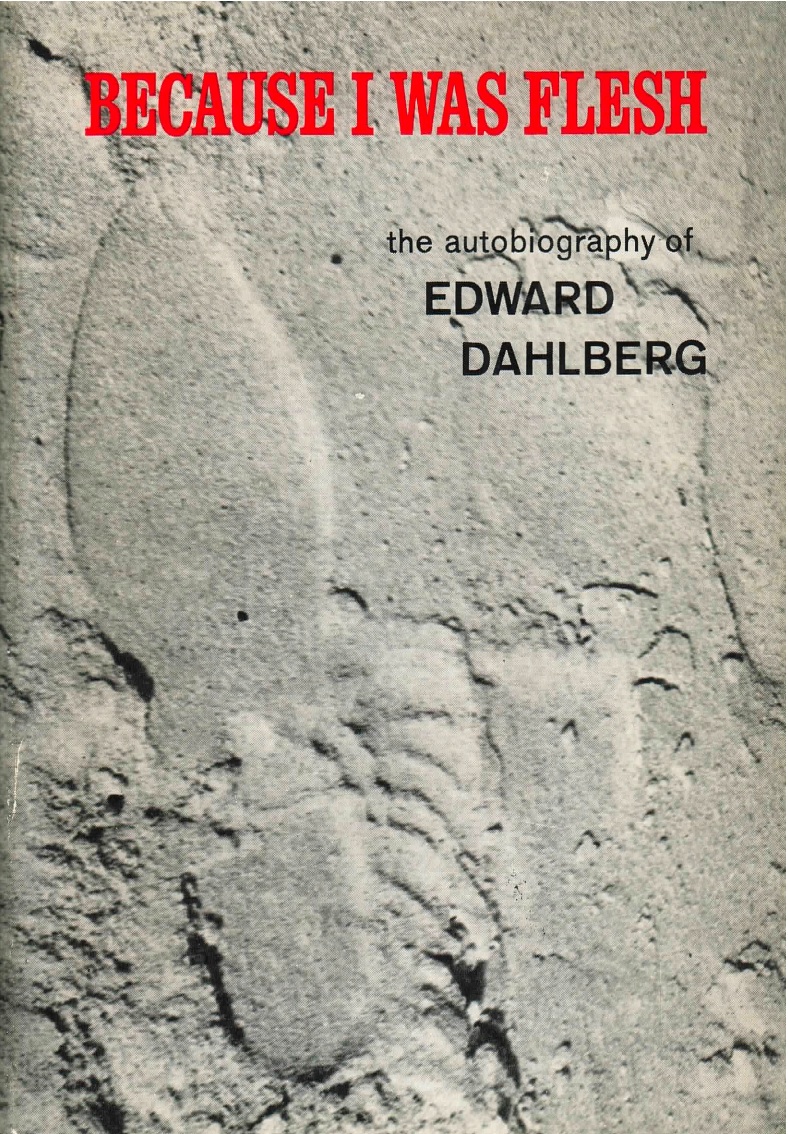

My thanks to the poet Stanley Burnshaw for expunging much of the dross from the manuscript of Because I Was Flesh.

E. D.

Copyright 1959, 1960, 1961, 1962, 1963 by Edward Dahlberg.

All rights reserved. Except for brief passages quoted in a newspaper, magazine, radio, or television review, no part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the Publisher.

First published as New Directions Paperbook 227 in 1967.

... because I was flesh, and a breath that passeth away and cometh not again.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Portions of this book first appeared in Best American Short Stories of 1962, Big Table, First Person, The Massachusetts Review, Prairie Schooner, Sewanee Review and The Texas Quarterly, to whose Editors my gratitude is offered, as to the National Institute of Arts and Letters and the Longview Foundation for grants which enabled me to complete it.

I

What moved you to t?

Why, flesh and blood, my lord; What should move men unto a woman else?

Tourneur

K ansas City is a vast inland city, and its marvelous river, the Missouri, heats the senses; the maple, alder, elm and cherry trees with which the town abounds are songs of desire, and only the almonds of ancient Palestine can awaken the hungry pores more deeply. It is a wild, concupiscent city, and few there are troubled about death until they age or are sick. Only those who know the ocean ponder death as they behold it, whereas those bound closely to the ground are more sensual.

Kansas City was my Tarsus; the Kaw and the Missouri Rivers were the washpots of joyous Dianas from St. Joseph and Joplin. It was a young, seminal town and the seed of its men was strong. Homer sang of many sacred towns in Hellas which were no better than Kansas City, as hilly as Eteonus and as stony as Aulis. The city wore a coat of rocks and grass. The bosom of this town nursed men, mules and horses as famous as the asses of Arcadia and the steeds of Diomedes. The cicadas sang in the valleys beneath Cliff Drive. Who could grow weary of the livery stables off McGee Street or the ewes of Laban in the stockyards?

Let the bard from Smyrna catalogue Harma, the ledges and caves of Ithaca, the milk-fed damsels of Achaia, pigeon-flocked Thisbe or the woods of Onchestus, I sing of Oak, Walnut, Chestnut, Maple and Elm Streets. Phthia was a bin of corn, Kansas City a buxom grange of wheat. Could the strumpets from the stews of Corinth, Ephesus or Tarsus fetch a groan or sigh more quickly than the dimpled thighs of lasses from St. Joseph or Topeka?

Kansas City was the city of my youth and the burial ground of my poor mothers hopes; her blood, like Abels, cries out to me from every cobblestone, building, flat and street.

My mother and I were luckless souls. She strove fiercely for her angels and was wretched most of her days in the earth. Moreover, if she failed, who hasnt? If she prayed for what she thought was her good, and none heeded her, that had to be too. Each one carries his own sack of woe on his back, and though he supplicate heaven to ease him, who hears him except his own sepulchre? Night covers the acts of man; could he lay his follies on the ground and in the light of the sun as he committed them, he would shriek like the owls for his tomb. We know nothing and understand nothing, and this is no boast. The trees are tender and the voices of the many rivers are pleasant, yet our bones quake every day.

She never desired to be miserable, and neither did I, but it is just as important to be unfortunate as it is to be happy. She sighed as often for the wheat as she pined for the chaff, not knowing one from the other. Many cry in trouble and are not heard, but to their salvation, declares St. Augustine.

My mother had two miserable afflictions, neither of which was she ever to overcome: her flesh which is my own and the world, that cursed both of us. Let me, O Lord, be most ungrateful to the world, comes from the mouth of Teresa, the Jewess of Avila.

There was no angel in Beersheba to comfort my mother or to take pity on her unquenchable thirst for the living waters: What aileth thee, Hagar? Nobody heard her tears; the heart is a fountain of weeping water which makes no noise in the world. The Kabbalists claimed that when man cries out, his voice pervades the Kosmos; stones are sentient and tremble for us when we are heavy with trouble, and the ground is our brother and keeper though man is not.

A tintype taken of my mother in her early twenties showed a long oval face with burning brown eyes and hair of the same color. She did not have thick features, and her hands had the soul of the pentagram, which Plato considered the geometric figure of goodness. There was much feeling in the appearance of her mouth, although most of her teeth had been removed by a quack dentist of Rivington Street in New York. Perhaps no more than four feet ten inches in height, health was her beauty. Lucian affirms that there are some who will be admired for their Beauty; whom you must call Adonis and Hyacinthus, though they have a nose a cubit long. My mothers long nose sorely vexed me. I dont believe I ever forgave her for that, and when her hair grew perilously thin, showing the vulgar henna dye, I thought I was the unluckiest son in the world. I doted on the short up-turned gentile nose and imagined myself the singular victim of nature in having a mother with a nose that was a social misfortune. Aside from her unchristian nose, what troubled me enormously was her untidiness. She slopped about the rooms in greasy aprons and dressed more like a rag raker or a chimney sweep. I was ashamed when we walked together in the streets, and when she showed a parcel of her winter drawers as she sat I suffered discomfiture.

This book is a burden of Tyre in my soul. It is a song of the skin; for I was born incontinent. Everything has been created out of lust, and He who made us lusts no less than flesh, for God and Nature are young and seminal, and rage all day long. I shall sing as Tyre, according to the Prophet Isaiah, like a harlot, and for seventy years.

It is a great pain to divulge the life of a mother, and wicked to betray her faults. Why then do I do it? I have nothing better to do with my life than to write a book and perhaps nothing worse. Besides, it is a delusion to believe that one has a choice. If this book is a great defect, then let it be; for I have come to that time in my life when it is absolutely important to compose a good memoir although it is also a negligible thing if I should fail. Fame, when not purchased, is an epitaph which the rains and the birds peck until the letters on the headstone are illegible.