First published 2003

by Routledge

11 New Fetter Lane, London EC4P 4EE

Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada

29 West 35th Street, New York, NY 10001

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group

This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2003.

2003 Dexter Hoyos

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

A catalog record for this book has been requested

ISBN 0-203-41782-8 Master e-book ISBN

ISBN 0-203-41929-4 (Adobe eReader Format)

ISBN 0-415-29911-X (Print Edition)

HANNIBALS DYNASTY

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

It is a pleasant task to acknowledge the people and institutions who have helped to make this work possible. My earliest debt is to Richard Stoneman, who expressed interest in the theme of Hannibals dynasty even before I began writing; and his support since the book was completed has been just as valued. The rest of his team at Routledge, and Frances Brown and Carole Drummond at The Running Head Ltd, have been consistently helpful and informative on every aspect of publication.

I should like to express my appreciation to the scholars, publishers and archivists who made available several of the illustrations for this book. In alphabetical order they are Archivi Alinari and Archivio Brogi of Florence, Italy; CNRS Editions, Paris, and Prof. M. H. Fantar; and Dr Matthias Steinart of the Archologisches Institut at the University of Freiburg, Germany.

I am grateful too to Sydney University for its continuing commitment to Greek and Roman studies, a rather endangered species in Australia, and its aids to research through grants of study leave and travel funds. Invaluable again have been the interest, courtesy and expertise of the University Library staff at every level, for without these my research task would have been hard indeed.

As always, it has been my wife Jann and our daughter Camilla who made it both possible and worthwhile. Hamilcar, Hasdrubal, and Hannibal and his brothers have not been the centre of their attention, but if Barcid family life was at all similar they were fortunate men.

Dexter Hoyos

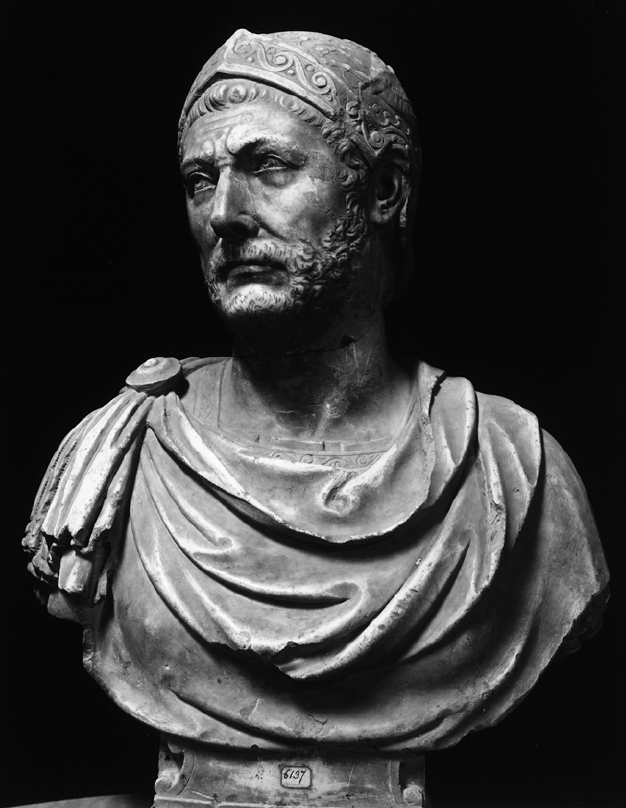

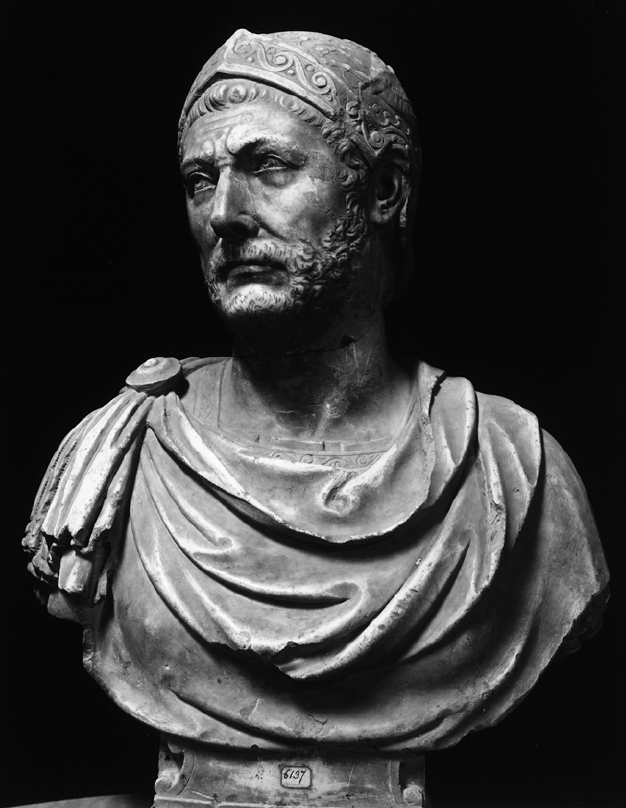

1 Hannibalbust found at Naples in 1667: identification not certain (reproductioncourtesy of Archivi Alinari, Firenze)

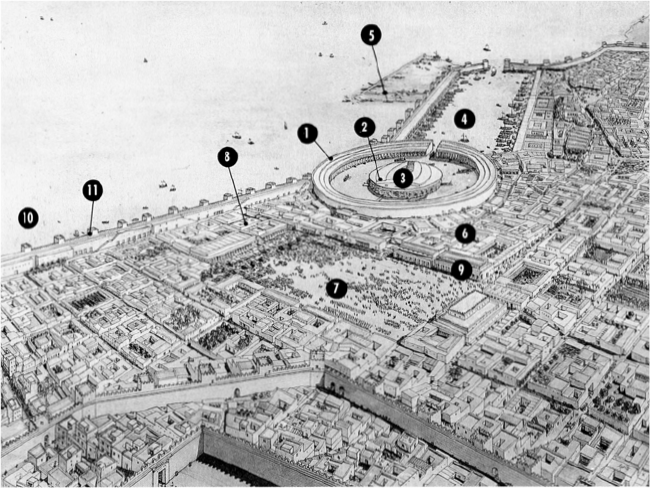

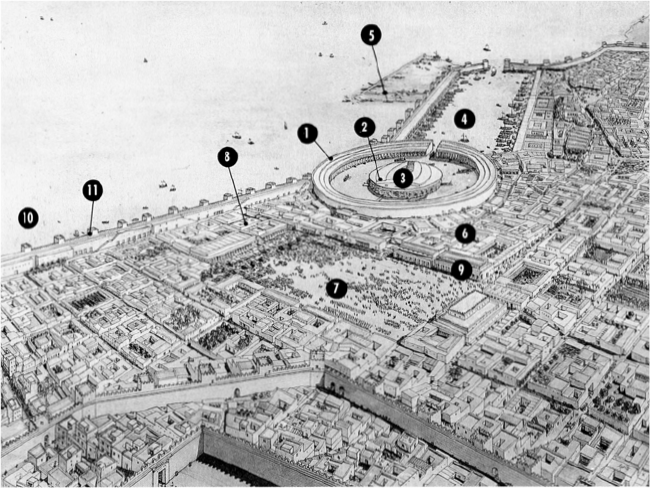

2 Carthage in Hannibals time: the ports region (reconstruction)

1 Naval port

2 The admiralty island

3 The admiralty pavilion

4 Merchant port

5 The Fabre quadrilateral (ancient quay)

6 Lower city: artisans and commercial district

7 Ag ora (central square)

8 Senate house

9 Public buildings

10 Coastline

11 City wall

From M. H. Fantar, Carthage: La cit punique (courtesy of CNRS Editions, Paris)

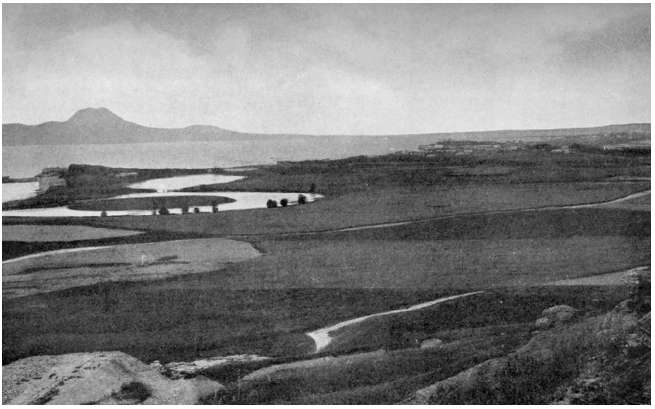

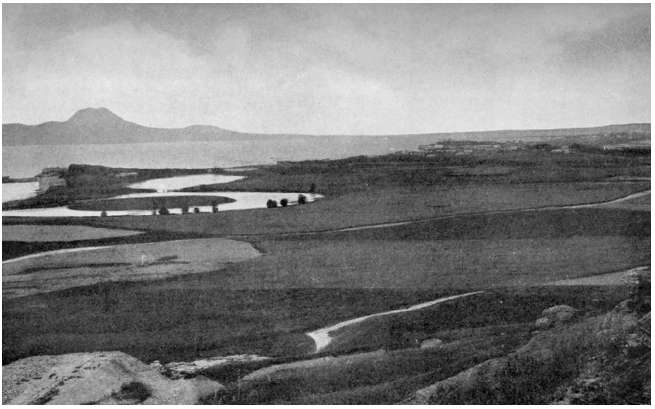

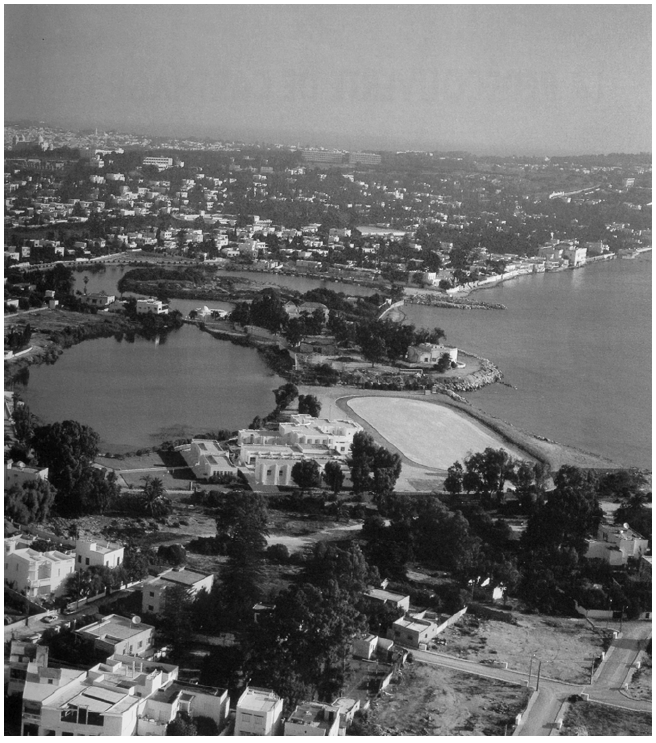

3 Carthage (ca. 1890)View from Byrsa hill towards the lagoons (the ancient artificial ports); on the horizon, the Cape Bon peninsula

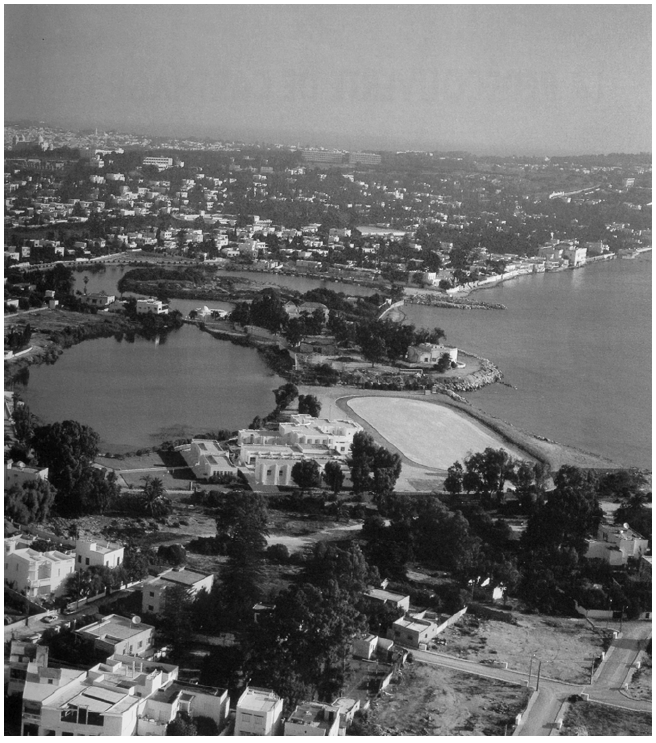

4 Carthage (ca. 1990)aerial view from the south: in the middle distance, Byrsa hill (Colline de St-Louis) from M. H. Fantar, Carthage: La cit punique (courtesy of CNRS Editions, Paris)

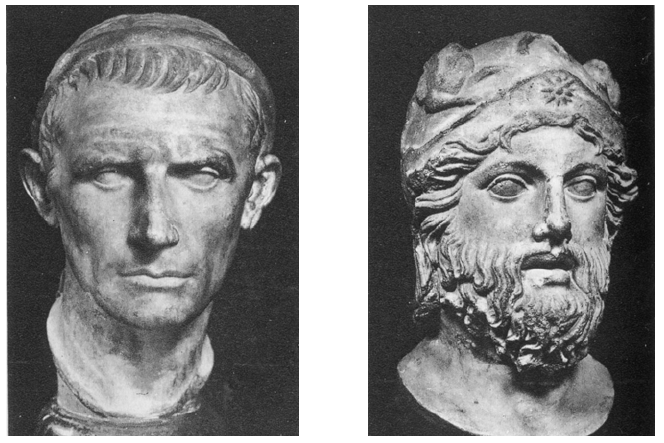

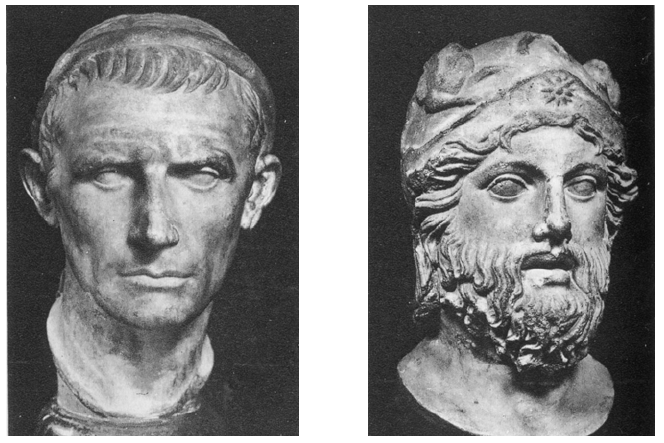

5 Antiochus III (l.) and Masinissa(?) (r.)portraits (presumed) in the Louvre and Capitoline Museums respectively

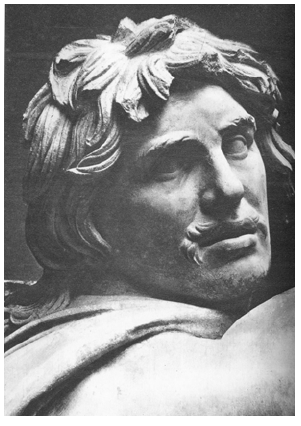

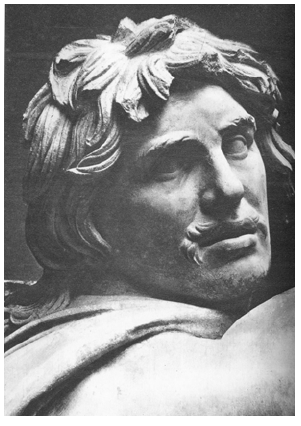

6 Gallic warrior (third century BC)detail of the famous statuary-group of a Gallic warrior slaying his wife and himself to avoid capture: from the Altar of Attalus I of Pergamum

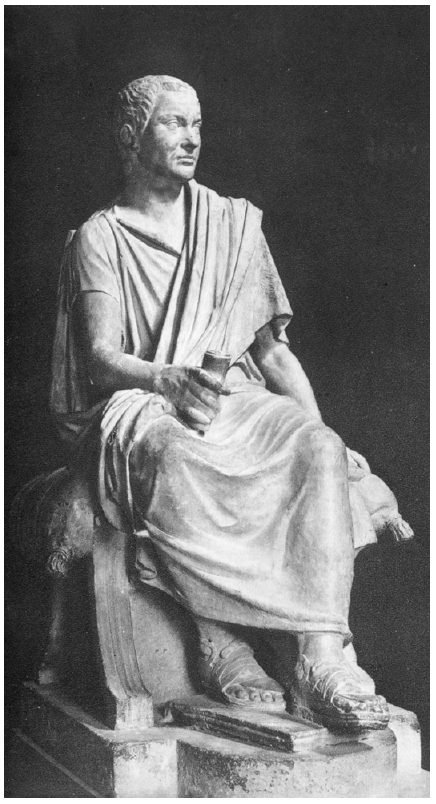

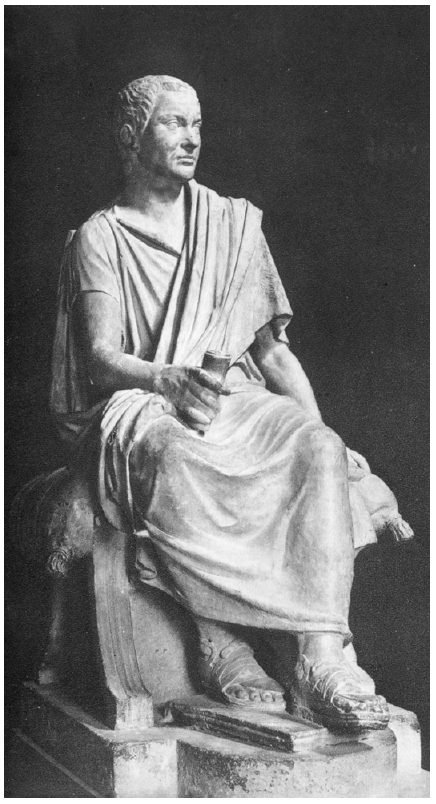

7 MarcellusHannibals vigorous opponent, killed in ambush in 208 BC: a late Republican or early Imperial statue

8 Scipiopresumed portrait, in bronze (reproduced courtesy of Archivio Brogi/Archivi Alinari, Firenze)

9 Philip V of Macedontwo coin-portraits of the king in his prime

10 Polybiuscommemorative stele from Kato Klitoria, in the Peloponnese, set up by a first-century AD descendant (reproduced courtesy of Dr Matthias Steinhart, Archologisches Institut, the University of Freiburg)

INTRODUCTION

Hannibal is the only Carthaginian who is still a household name. As leader of the Carthaginians and their empire in the Second Punic War from 218 to 201 BC, he made it touch and go whether they or the Romans would come to dominate the Mediterranean west, and after that, more or less inevitably, the east. He belonged to a remarkable family. Had the Carthaginians won the war and changed the course of ancient history, the victory would have been due in great part to Hannibal and his kinsmen, who had rebuilt Carthaginian power after its catastrophic defeat in 241 at Roman hands.

In taking his city to its most extensive and eventful level of power Hannibal was the third, the greatest and the last of a republican ruling dynasty. His father Hamilcar, nicknamed Barca (hence the convenient family sobriquet Barcid) came to prominence in 247, the year Hannibal his eldest son was born. Hamilcar and his son-in-law Hasdrubal preceded Hannibal between 237 and 221 as effective rulers of Carthage and creators of a land empire that replacedand outdidthe citys lost island possessions. Hannibal built on their base.

How the Barcids dominance was founded and how maintained, what each leader in turn aimed to achieve with it, what they actually accomplished, and how and why Barcid supremacy in the end collapsedand then staged a brief revivalare the themes of this study. The theme involves politics, international relations, strategy and geography, for the Barcid generals were not only Carthages de facto leaders of government but her official commandersin- chief, and the two rles were bound closely together.

The Carthaginian state had enjoyed success before, but never on the Barcid scale or with the potential to change all of ancient history. This achievement was the more remarkable as Hamilcar and his successors, uniquely in Punic history, exercised decades of dominance not from their home city but from hundreds of miles away, first in Spain and then in Italy. Hamilcars adroit handling of the war against rebel mercenaries and subject Libyans in North Africa, from 241 to 237, made him supreme in Punic affairs, and his successes in Spain followed by Hasdrubals consolidation cemented the Barcid supremacy. Yet they and then Hannibal were not military dictators: all three were elected to their commands by the citizens of Carthage as well as by their armies, and all relied on a supporting network of kinsmen, friends and supporters to sustain their political dominance at Carthage.