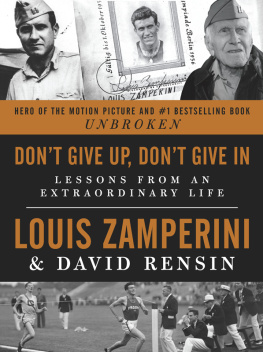

"Don't Give Up, Don't Give In"

Devil at My Heels

For Cynthia, my children Cissy and Luke,

and my grandson, Clayton

The 1929 Geneva Convention Relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War

Article 2:

Prisoners of war are in the power of the hostile Power, but not of the individuals or corps who have captured them. They must at all times be humanely treated and protected, particularly against acts of violence, insults and public curiosity. Measures of reprisal against them are prohibited.

A smooth sea never made a good sailor.

Anonymous

CONTENTS

L ouis Zamperinis life is a story that befits the greatness of the country he served: how a commonly flawed but uncommonly talented man was redeemed by service to a cause greater than himself and stretched by faith in something bigger to look beyond the short horizons of the everyday. What he found, beyond the horror of the prison camps and the ghosts he carried home with him, is inspiring.

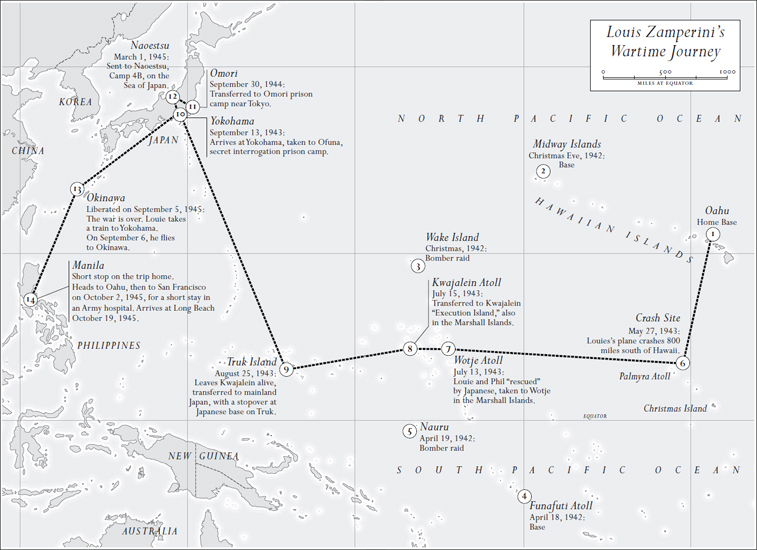

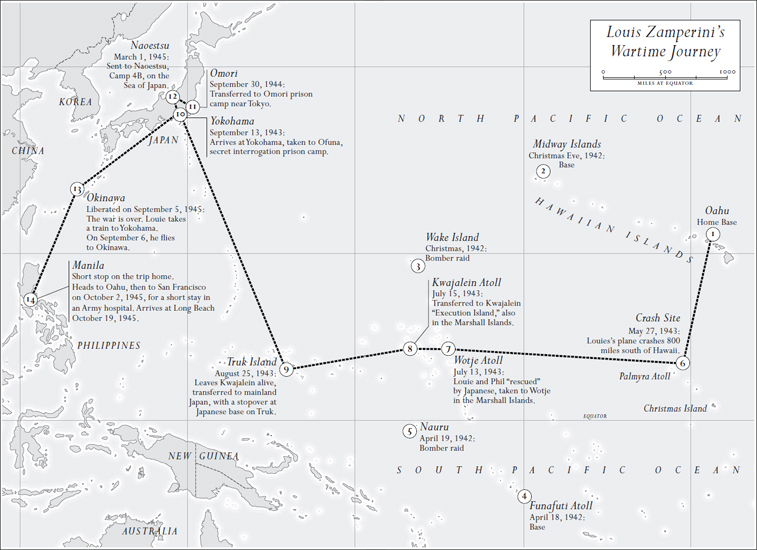

The remarkable life story of Lucky Louie takes him from the track as an Olympic runner in Berlin in 1936, where he met Hitler, to a raft in the Pacific fending off man-eating sharks and Japanese gunners to prisoner of war camps where rare goodness coexisted with profound evil to a heros return to America, where he would first plumb the depths of despair and self-destruction before soaring to heights he could not have foreseen or imagined.

This book contains the wisdom of a life well lived, by a man who sacrificed more for it than many people would dare to imagine. It is brutally honest and touchingly human, comfortably pedestrian and spiritually expansive. It should invoke patriotic pride in readers who will marvel at what Louis and his fellow prisoners gave for America, and what we gained by their service. It holds lessons for all of us, who live in comfort and with plenty in a time of relative peace, about what we live for.

More than a story of war, its lessons grow out of Louiss wartime experience. Its moral force is derived from the very immorality of American prisoners savage treatment by their wartime captors, and the way Louis would ultimately drive away their demons. Rather than destroying Louiss moral code, war and recovery from wars deprivations revealed the mystery of Louiss faith in causes far greater than the requirements of survival in a temple of horrors.

Whether in religion, country, family, or the quality of human goodness, faith sustains the struggle of men at war. Before I went off to war, the truth of war, of honor and courage, was obscure to me, hidden in the peculiar language of men who had gone to war and been changed forever by the experience. I had thought glory was the object of war, and all glory was self-glory.

Like Louis Zamperini, I learned the truth in war: There are greater pursuits than self-seeking. Glory is not a conceit or a decoration for valor. It is not a prize for being the most clever, the strongest, or the boldest. Glory belongs to the act of being constant to something greater than yourself, to a cause, to your principles, to the people on whom you rely, and who rely on you in return. No misfortune, no injury, no humiliation can destroy it.

Like Louis, I discovered in war that faith in myself proved to be the least formidable strength I possessed when confronting alone organized inhumanity on a greater scale than I had conceived possible. In prison, I learned that faith in myself alone, separate from other, more important allegiances, was ultimately no match for the cruelty that human beings could devise when they were entirely unencumbered by respect for the God-given dignity of man. This is the lesson many Americans, including Louis, learned in prison. It is, perhaps, the most important lesson we have ever learned.

Through war, and in peace, Louis Zamperini found his faith.

October 2002

I VE ALWAYS BEEN called Lucky Louie.

Its no mystery why. As a kid I made more than my share of trouble for my parents and the neighborhood, and mostly got away with it. At fifteen I turned my life around and became a championship runner; a few years later I went to the 1936 Olympics and at college was twice NCAA mile champion record holder that stood for years. In World War II my bomber crashed into the Pacific Ocean on, ironically, a rescue mission. I went missing and everyone thought I was dead. Instead, I drifted two thousand miles for forty-seven days on a raft, and after the Japanese rescued/captured me I endured more than two years of torture and humiliation, facing death more times than I care to remember. Somehow I made it home, and people called me a hero. I dont know why. To me, heroes are guys with missing arms or legs or livesand the families theyve left behind. All I did in the war was survive. My trouble reconciling the reality with the perception is partly why I slid into anger and alcoholism and almost lost my wife, family, and friends before I hit bottom, looked upliterally and figurativelyand found faith instead. A year later I returned to Japan, confronted my prison guards, now in a prison of their own, and forgave even the most sadistic. Back at home, I started an outreach camp program for boys as wayward as I had once been, or worse, and I began to tell my story to anyone who would listen. I have never ceased to be amazed at the response. My mission then was the same as it is now: to inspire and help people by leading a life of good example, quiet strength, and perpetual influence.

Ive always been called Lucky Louie. Its no mystery why.

I WAS BORN in Olean, New York, on January 26, 1917, the second of four children. My father, Anthony Zamperini, came from Verona, Italy. He grew up on beautiful Lake Garda, where as a youngster he did some landscaping for Admiral Dewey. My dad looked a little bit like Burt Lancaster, not as tall but built like a boxer. His parents died when he was thirteen, and soon after that he came to America and got a job working in the coal mines. At first he used a pick and shovel and breathed the black dust. Then he drove the big electric flatcars that towed coal out of the mines. He worked hard all his life, always had a job, always made money. But he wanted more, so he bought a set of books and educated himself in electrical engineering.

Anthony Zamperini wasnt what youd call a big intellect, but he was wise, and thats more important. His wisdom sustained us.

My mother, Louise, was half-Austrian, half-Italian, and born in Pennsylvania. A handsome woman, of medium height and build, Mom was full of life, and a good storyteller. She liked to reminisce about the old days when my big brother, Pete, my little sisters, Virginia and Sylvia, and I were young. Of course, most mothers do. Her favorite storiesor maybe they were just so numerouswere about all the times I escaped serious injury or worse.

Shed begin with how, when I was two and Pete was four, we both came down with double pneumonia. The doctor in Olean (in upper-central New York State) told my parents, You have to get your kids out of this cold climate to where the weather is warmer. Go to California so they dont die. We didnt have much money, but my parents did not deliberate. My uncle Nick already lived in San Pedro, south of Los Angeles, and my parents decided to travel west.

At Grand Central Station my mother walked Pete and me along the platform and onto the train. But five minutes after rolling out, she couldnt find me anywhere. She searched all the cars and then did it again. Frantic, she demanded the conductor back up to New York, and she wouldnt take no for an answer. Thats where they found me: waiting on the platform, saying in Italian, I knew youd come back. I knew youd come back.

Next page