OTHER BOOKS

BY SAMUEL HAWLEY

Speed Duel: The Inside Story of the LandSpeed Record in the Sixties

The Imjin War: Japans Sixteenth-Century Invasionof Korea and Attempt to Conquer China

Americas Man in Korea: The Private Lettersof George C. Foulk, 18841887

Inside the Hermit Kingdom: The 1884 KoreaTravel Diary of George Clayton Foulk

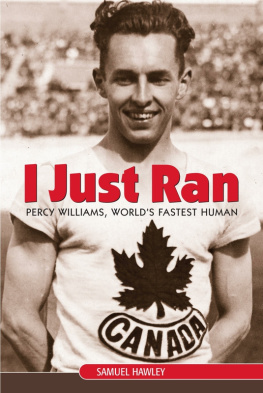

I JUST RAN

Copyright 2011 Samuel Hawley

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrievalsystem, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without prior written permissionof the publisher, or, in Canada, in the case of photocopying or other reprographic copying, a licence from Access Copyright (the Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency).

RONSDALE PRESS

3350 West 21st Avenue

Vancouver, B. C. Canada V6S 1G7

www.ronsdalepress.com

Typesetting: Julie Cochrane, in Granjon 11.5 pt on 15

Cover Design: Julie Cochrane

Front Cover Photo: Percy Williams in 1928, moments after winning the

100-metre Olympic gold medal (BC Sports Hall of Fame and Museum)Back Cover Photo: Percy Williams in 1928, winning the 200-metre Olympic

gold metal (BC Sports Hall of Fame and Museum)

Ronsdale Press wishes to thank the following for their support of its publishing program:the Canada Council for the Arts, the Government of Canada through the Canada BookFund, the British Columbia Arts Council, and the Province of British Columbia throughthe British Columbia Book Publishing Tax Credit program.

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Hawley, Samuel Jay, 1960

I just ran: Percy Williams, worlds fastest human / Samuel Hawley.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

Electronic monograph in HTML format.

Issued also in print format.

ISBN 978-1-55380-132-0

1. Williams, Percy, 19081982. 2. Runners (Sports) CanadaBiography. I. Title.

GV1061.15.W55H39 2011a 796.42'2092 C2011-903007-1

Prologue

THE REPORTERS CLUSTERED round the young sprinter after therace and the question they kept asking was: How did you feel justbefore the gun sounded? He answered politely but the intrusivenessgrated. What a fool question, he groused to his coach after the scrumfinally dispersed. How does anybody feel before a race scared asblazes.

It was more or less how all six runners had felt as they took theirmarks that July afternoon for the hundred-metre final of the 1928Amsterdam Olympics. The fear had taken hold the night before asthey lay in their beds trying to cope with their nerves and had only gotten worse as race time drew nearer. A lot of coaches held that beingscared was a good thing for a runner, a necessary building up of emotional tension that could then be unleashed in one almighty effort. Butthat didnt make it any easier to bear certainly not in that final hourin the dressing room, or in that lonely walk down the tunnel that ledto the track, or in those last few moments when you strip to your shortsand stand exposed to the thousands and wish you were somewhere,anywhere, else.

The six runners had endured two rounds of qualifying heats theprevious day and the semifinals two hours before, a winnowing thathad seen eighty-one others fall by the wayside. For one of the finalistsa gold medal lay at the far end of the track. For the rest it would be,quite literally, the agony of defeat. It had rained earlier that day; thesky was leaden and the air chilly, far from ideal conditions for sprinting. They dug their start holes in the damp cinders at the chalk line,then took off their warm-up gear and did some final limbering, tryingto control the surging adrenalin as they waited to be called to theirmarks. To the watching crowd the two Americans on the outside,Wykoff and McAllister, seemed good bets to win. So did the muscularfigure of London in lane four, representing Britain, and the Germanace Lammers in two.

As for the young man in lane three a Canadian, was he? heappeared hopelessly outclassed. At 126 pounds on a five-foot-seven-inch frame, he was surely too scrawny for such top-flight competition.Then there was the matter of his experience: he didnt have any, atleast not in the big time. This meet was his first taste of internationalcompetition.

No, all things considered, the young man didnt have much of achance. He was probably down there falling to pieces under the pressure, poor kid.

But he wasnt falling to pieces. He was scared, all right, pacing backand forth like a caged lynx, his heart beating a hole through his chest.But he was holding it together, repeating to himself the words hiscoach had used to soothe him moments before in the change room: Itsjust another race. Its just another high school race.

The six runners were called to their marks. The set command. Thecrack of the gun. A flurry of pumping legs and arms and then thatslight figure emerging in front to breast the tape and claim gold witha leap. Pandemonium in the stands, a delight that transcended bordersthat such an unlikely youngster had won. And in the press box grinning journalists shaking their heads and beginning to scribble, muttering incredulously: Who is this Canadian kid?

The kid was Percy Williams of Vancouver and he wasnt finished.Two days later he captured the two-hundred-metre gold medal as well,completing the Olympic sprint double, the Games most glamorousfeat. The following winter he swept the US indoor track circuit,silencing critics who claimed his Olympic wins were a fluke. In 1930he broke Charlie Paddocks nine-year-old world record for the hundred metres, setting a new mark that would stand until the advent ofJesse Owens. In 1932 he returned to the Olympics to defend his double sprint crown, something never before successfully accomplished.And in between he engaged in an ongoing speed duel with some of thefleetest men on the planet, arch rivals Frank Wykoff and Eddie Tolanforemost among them a battle for track supremacy and the titleWorlds Fastest Human.

Yet through it all he remained a reluctant hero and very much anenigma. When pressed to explain his secret for winning, he would onlyshrug and say, I just ran.

Percy Williams was showered with such acclaim in his day that hewas almost as well-known as contemporaries Babe Ruth and JackDempsey, a remarkable degree of fame for a runner, particularly onewho so assiduously shunned the spotlight. It wasnt just his athleticprowess that attracted all the attention. Percys own story, the quintessential underdog tale, was immensely appealing. He wasnt the product of some top-flight collegiate track program. He wasnt a memberof a renowned athletic club. He didnt have a big-name coach or anypowerful backing. He was just a kid from nowhere with a talent forrunning, discovered and pushed to stardom by a man named BobGranger who earned his living mopping floors at a school. The unlikelypair lacked the basic facilities that were elsewhere taken for granted,Percy doing most of his running on grass fields and dirt tracks. Theyhad no money. To get Percy to the nationals in Toronto they had toraise funds themselves to buy him a train ticket while Bob worked inthe pantry car for his passage. They didnt realize that nobodies likethem werent supposed to have a chance and so they doggedly kept atit until they made it all the way to the top.

And there was more. There was something about Percy himself thatthe press and the public found irresistibly attractive. He was clean-cutand clean-living, delicate yet tough, vulnerable yet resolute, obedientto his coach and his father, devoted to his mother, loyal to his hometown and nation the embodiment, in short, of qualities that allowedjust about everyone to see in him whatever it was that they yearned for.Even the dourest of officials and sharpest of promoters couldnt helpgetting just a little maudlin over Percy. He was so touchingly shy; sohumble despite his talents; so much the epitome of the amateur tradition, an athlete who did a little training after school shockingly little,by todays standards and still became a champion.