Together, these three works make up this book, and although they are separate works in themselves, they are best read in the order set out, as it makes the full story easier to understand. The chosen order is partly chronological, but also that of the most objective work to the most subjective, and for the author, the most personal.

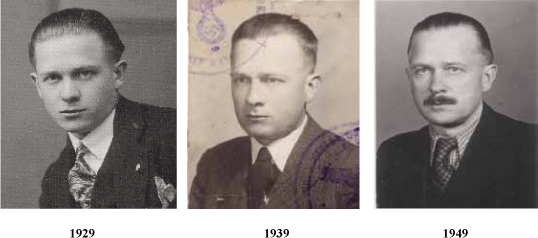

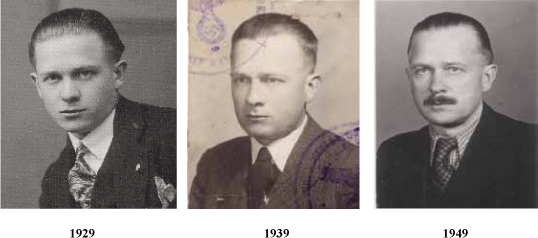

The photographs on the front cover of this book are taken from the 1949 travel document pictured on page 117 of A Righteous Pole. The metal staples that attach them to the document may be seen as a metaphor for the flight of the Krzeminski family across the barbed-wire entanglements of the Iron Curtain and those which surrounded the barracks the family occupied in Germany. These, a few months before, had been concentration camps.

The photo on the back cover shows the family after they had successfully established themselves in Australia.

This book tells the story of the Krzeminski family in Poland, the effect the Nazi and Soviet regimes had on them, and their subsequent life in Australia.

Before 1945 the family name was Skrzypczak. They had already spent five years successfully deceiving the Nazi Gestapo. Now, with three small children, they faced the wrath of the secret police of the Polish (Communist) Department of Security (the UB), as well as the secret police of the Soviet Peoples Commissariat for Internal Affairs (the NKVD, later to become the KGB). The latter was the most thorough and effective security and intelligence service in the world, and the most ruthless. It had already murdered many millions of people and was in the process of murdering countless more.

It was a matter of life or death, so using whatever means it took, including perjury, forgery and bribery, the Skrzypczaks changed their identity in the spring of 1945 and their name became Krzeminski. It meant making certain that there were no means of tracing them back to their former identity. This involved altering not only names, but also birthdays, places of birth, maiden names etc. It entailed creating a whole fictitious past life. It meant breaking off contact with relatives and friends. It meant that personal letters, photographs, and identifying clothing labels had to be destroyed. It meant fleeing to another part of the country. It meant leaving behind their adopted daughter. The family, in effect, became new people.

Their efforts were successful and they were eventually able to escape from Poland across the Iron Curtain. In 1949 the Krzeminskis arrived in Australia.

Here, Peter became Kreminski in 1958, Eva became OLeary in 1969, Lucjan died in 1984 and Helena died in 1989, and so the name Krzeminski was not carried on to the next generation.

Ludwik Skrzypczak

b. 1904 Germany

Lucjan Krzeminski

d. 1984 Australia

A RIGHTEOUS POLE

Translated and annotated by his son

Peter Kreminski

With the assistance of Joanne Cichinski

and a contribution from Peter Lada

Second Edition

Adelaide 2010

Ludwik Skrzypczak, an industrious, intelligent and energetic Pole, proud of his Polish ancestry, active in the re-establishment of the country after the First World War, was frustrated in his personal ambitions He made the decision in 1939 to become a German and achieved his goals, but he had sold his soul to the devil.

In 1945, when the even bigger devil appeared, he was faced with retribution.

So he changed his identity and became Lucjan Krzeminski.

I have Joanne Cichinski (nee Jadczak) to thank for her enthusiasm and many hours of invaluable help with the translation, editing and extensive proof-reading of this edition. Her support is deeply appreciated.

I thank Julie Piesiewicz (nee Dagnall) for her meticulous proof-reading and many helpful suggestions; Margaret Allen for her feed-back and suggestions; and Adam Kreminski for his advice as to how to make this work more understandable to the younger generation, and for help in typing and collating of the material.

Former Polish Army lieutenant-colonel, Zbigniew Grabczewski OAM, enabled me to search for valuable information from Polish government archives through his friendship with the former Polish Prime Minister, General Kiszczak. He also gave me another perspective on 20th century Polish history and politics, and was the first to indicate that my father must have been a Treuhaender (a form of administrator) during the war.

I also acknowledge the trouble that Ludwiks five grandchildren: Amy, Brendan, Esther Michael and Adam took to contribute to the Epilogue, thus giving this work the very valuable perspective of modern young adults, and so making the story complete.

I thank Peter Lada for establishing contacts with historians in Poland, and for researching and supplying information pertaining to my fathers story. Peter also stimulated me to learn more about Polish history and to review and reappraise my preconceptions about present Polish attitudes to WW2. His contribution of two essays about my father in both English and Polish is invaluable, as this lends balance and another perspective to the work.

The wider scope that the research for this, the second edition, involved meant that it took over a year to complete. I am particularly thankful to my wife, Veronica Kreminski (nee Piesiewicz), who showed more forbearance than I had the right to expect whilst also proof-reading and providing continual encouragement, advice and support during these many months.

Even now, seventy years after the event, some Polish people have a completely different attitude to what my father did in 1939 than non-Poles. Turning himself back into a German at the beginning of World War 2 is generally looked upon by Australians as an understandable decision given the circumstances. There are, however, Poles who still look at his action as that of a traitor to his own country, something which one should be ashamed of and not speak of, let alone write about.

Throughout the years I have experienced many negative reactions to my father changing his nationality before I was born. For example, patients have left me, or treated me with disdain, even pity. On my visits to Poland my uncle did not introduce me to his own sons - even in 1997. My female cousins have never reciprocated my contacting them. Australians of the same migrant background as myself have hushed me up when I spoke openly about the subject. Just last year family friends looked askance on hearing about my real background.