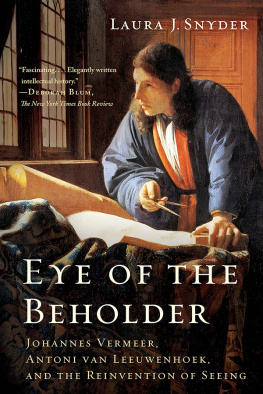

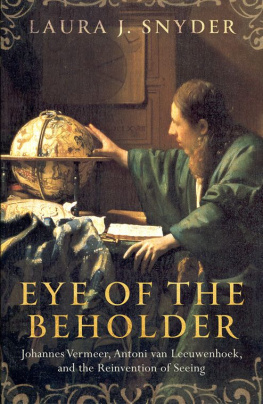

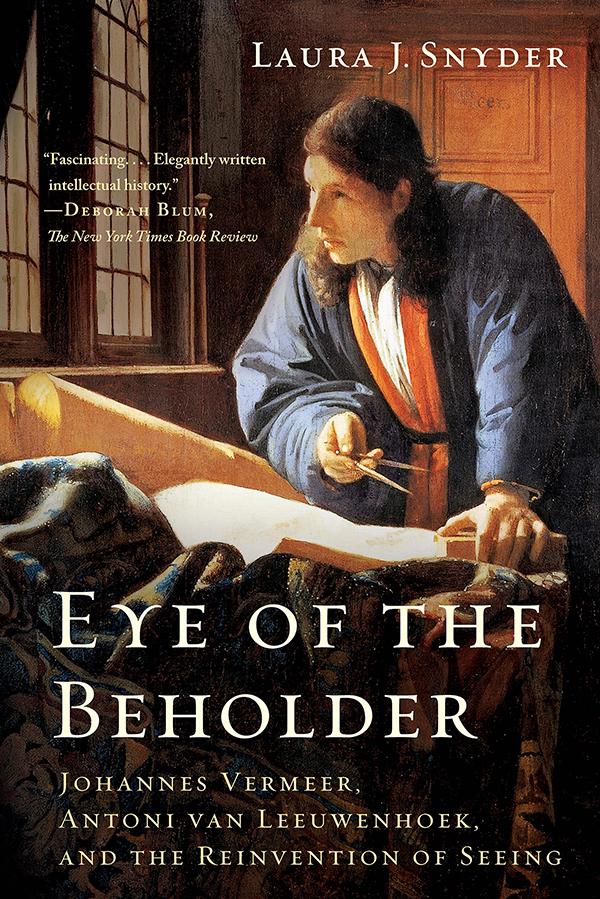

EYE

OF THE

BEHOLDER

Johannes Vermeer,

Antoni van Leeuwenhoek,

and the

Reinvention of Seeing

LAURA J. SNYDER

For John

Study the science of art. Study the art of science. Develop your sensesespecially learn how to see.

LEONARDO DA VINCI (14521519)

Painting is a science and should be pursued as an inquiry into the laws of nature. Why, then, may not a landscape be considered as a branch of natural philosophy, of which pictures are but experiments?

JOHN CONSTABLE,

The History of Landscape Painting (1836)

Hold, as twere, the mirror up to nature.

WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE,

Hamlet, III, II (ca. 1600)

Contents

EYE OF THE BEHOLDER

-1-

I T IS A bright day in August of 1674.

Leeuwenhoek is staring through a flat, oblong brass holder about three inches long. In the center of the holder is a tiny glass bead he made himselfhow he did so, whether by grinding the lens or by blowing it from molten glass, is a secret that Leeuwenhoek has jealously guarded. Attached to the back of the strange device is a thin metal rod supporting a small glass tube that contains a drop of water taken from the Berkelse Mere, an inland lake located a two hours walk from Delft. Pressing the metal holder closer to one eyeso that it is almost touching his facein order to peer at the water in the tube through the glass bead, Leeuwenhoek is shocked to see not a clear pool, but a veritable aquarium filled with minuscule, swimming creaturesabout a thousand times smaller than the tiniest cheese mites, he reckons. Some of these little animals are shaped like spirally wound serpents, some are globular, others elongated ovals; he records that the motion of... these animalcules in the water was so swift, and so various, downwards, and round about, that I confess I could not but wonder at it. Leeuwenhoek has just discovered a new world never before even imagined: the microscopic world.

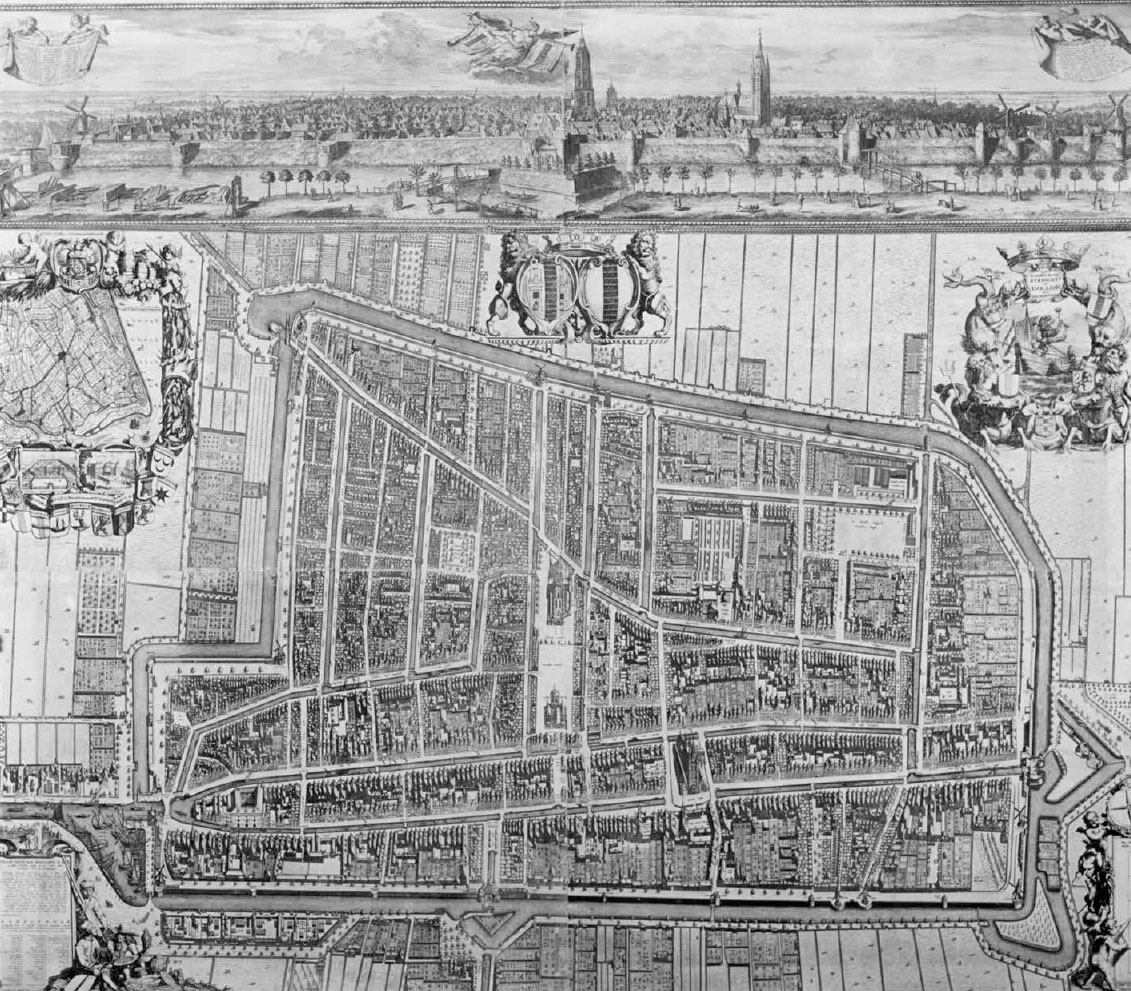

-2-

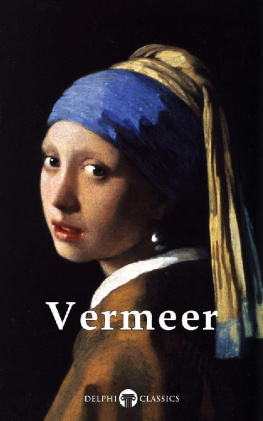

In an attic diagonally across the Market Square from Leeuwenhoeks house, another of Delfts geniuses is at work. Like his neighbor, Johannes Vermeer was secretive about his methods, so we cannot be certain how he painted his mature works of exquisite luminosity, works that show an exciting intimacy with optical effects seen only through lenses. But given the evidence we may reasonably imagine that, on this fine day in August, Vermeer is bent over a table, looking at a wooden box with an open hinged top, while holding his long, dark robe over his head. On one end of the box is a short tube holding a piece of glass ground to the shape of a lentilhence its name, a lens. At the top of the box sits a piece of flat glass. Vermeer has placed the tube with the lens in the direction of a scene he composed next to the rooms large window, which also has its shutters thrown wide open. Vermeer has draped a curtain between himself and the window, which blocks a little of the light flooding in. A young woman, in a yellow satin skirt, a white bodice, and a brilliant blue overdress, sits at a virginal, an instrument popular with the rich merchant class in Delft (and probably borrowed by Vermeer for the occasion). Her fingers rest on the keys while her face turns to Vermeer, as if waiting for him to tell her to begin to play. On the wall behind the woman hangs a large picture of a brothel scene by another painter, a picture that is owned by Vermeers mother-in-law, as is the house we are in now.

Under his robe, Vermeer gazes at the flat glass on the top of the box. The entire scene is visible on the glass, including its precise proportions and correct three-dimensional perspective rendered in a two-dimensional image. Vermeer is as astonished as ever to observe that the colors on the glass are even more jewel-like than they appear to the naked eye, the areas of shadow even more strongly contrasted with the patches of light, the contours of figures beautifully softened. He pays particular attention to the way the foreground and background are out of focus when the rest of the scene is sharp, the way the highlights appear brightly where the sun hits reflective surfaces, and how the relative tonal valuesthe way different colors look under different light conditionsare represented fully, more so than they are by the naked eye.

Vermeer is looking through a camera obscura, an optical device that, in earlier versions, had long been known to natural philosophers and natural magicians; it was employed in the past to observe solar eclipses safely and to amaze and delight audiences with living pictures. A precursor to the photographic camera, but without the light-sensitive film, the box-type camera obscura is a light-tight wooden chamber with a hole or lens on one side. It projects an inverted and reversed image of the scene either upon a glass plate or oilpaper on the top of the device or onto a nearby wall or canvas (by the use of a mirror the image can be made upright). Earlier versions were simply a dark roomthus the name, Latin for dark chamberwith a tiny aperture of five to ten millimeters letting in light from the sun outside. The spectator, sitting inside the room, would see the inverted and reversed image of the outside scene projected on the wall opposite the hole. These whole-room cameras were followed by versions in which a tented-off area or booth could be created inside to view a scene that was set up within the room. The invention of the box-type camera obscura came next.

Vermeer is looking through the camera not to trace its image onto translucent paper placed on the glass at the top of the box, or to angle the mirror so that the image is projected onto his canvas, but to experiment with the optics of the scene. By rearranging the composition, he can manipulate the type of light effects he has learned to exploit so masterfully. Vermeer sees that if the light hits the virginal just so, he will need a highlight of lead white paint there, on the right front leg. But the geometry of the picture seems to him to require another highlight on the front of the instrument, depicting a reflection of the womans forearm, where the light is not causing a reflection. Vermeer is no slave to the optics of the camera obscura.

By looking through the camera obscura, Vermeer has become expert in the way that light affects how we see the world. He has seen the world as we do not normally see it, revealed in surprising new ways invisible to the naked eye. Like the microscope, the camera obscura disclosed to its seventeenth-century users truths about the natural world otherwise inaccessible to the senses. As the diplomat, natural philosopher, and art enthusiast Constantijn Huygensan acquaintance of both Vermeers and Leeuwenhoeksput it, with the advent of the camera obscura, all painting is dead by comparison, for this is life itself, or something more elevated, if one could articulate it.

Next page