Acknowledgements

Thanks and acknowledgements are due to Mr John Abbott; Mr Hugo Beit; Miss Naomi Boneham (Thomas H Manning Polar Archives, Scott Polar Research Institute, Cambridge); The Bodleian Library, Oxford and Mr Christopher Osborn (Margot Asquith Papers); The British Library (Lord Reading Papers); Mr David Cane; Mr Colin Harris (Bodleian Library, Oxford); to Mr George Liebmann for information on Edgar and James Speyer; Professor Margaret Macmillan for facilitating a stay at St Antonys College, Oxford, under a twinning agreement with Wolfson College, Cambridge; Mrs Sarah Maspero (Hartley Library, University of Southampton); Professor James Moore; Mr David Murrell and Ms Susan Smith (Sea Marge Hotel, Overstrand); the National Archives, Kew (Home Office and Treasury Solicitors Papers); Mrs Natalie ODell for information on the Orpen portrait of Edgar Speyer; Mr Arnold Rosen; Mr Peter Sigler; Ms Katalin Sinkovics (Killik & Co); Ms Jennifer Thorp (New College, Oxford); Mrs Gabrielle Thorp (for her brief but valuable comments on Leonora Speyer, her grandmother); Mr David Watson; Mr W S Robinson and Dr Theo Shulte. Finally I must record my gratitude to Dr Leanne Langley for indicating some useful sources of information and for setting me right on several matters of fact; to Ellie Shillito, of Haus, for her editorial solicitude; to Sir Louis Blom-Cooper for his generous foreword; above all to Dr Philip Webb of the Cities Centre, University of Toronto, for his patience, meticulous attention and informed and expert suggestions. For errors and misapprehensions responsibility is of course entirely mine.

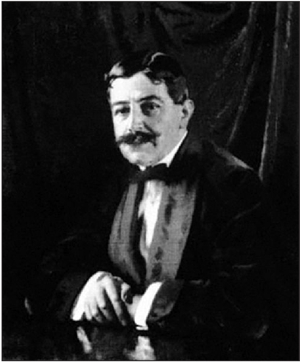

List of Illustrations

BANKER, TRAITOR, SCAPEGOAT, SPY?

(William Orpen, 1914)

The portrait was exhibited at the Royal Academy

Summer Exhibition, 1914

Antony Lentin

Banker, Traitor,

Scapegoat, Spy?

The Troublesome Case of Sir Edgar Speyer

An Episode of The Great War

With a Foreword by Sir Louis Blom-Cooper, Qc

First published in Great Britain in 2013 by

Haus Publishing Ltd

70 Cadogan Place

London SW1X 9AH

www.hauspublishing.com

Copyright Antony Lentin, 2013

Foreword copyright Sir Louis Blom-Cooper, 2013

The moral right of the author has been asserted

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ebook ISBN 978-1-908323-17-0

All rights reserved.

in memoriam

Roger Asbury (4/10/192011/03/2011)

happy warrior 19391945

A merry heart maketh a cheerful countenance

ANTONY LENTIN is a Senior Member of Wolfson College, Cambridge, a Fellow of the Royal Historical Society and a Barrister. Formerly a Professor of History and Law Tutor at the Open University, he is the author of Guilt at Versailles: Lloyd George and the Pre-History of Appeasement (1985), Lloyd George and the Lost Peace (2001), The Last Political Law Lord: Lord Sumner (18591934) (2009) and General Smuts (2010). He has published widely on 18th-century Russia and has edited The Odes of Horace for Wordsworth Classics.

Contents

Foreword

There is a danger, not to be underestimated, in resurrecting past miscarriages of justice, with the prospect that glaring faults of yesteryear will illuminate lessons to be learnt today. Very often the defects of such cases will have been cured by subsequent judicial rulings or legislative action. What remains is the intrinsic interest only; legal history has, of course, its own fascination. This book is a classic example of avoidable damage. Professor Lentin not merely revives an unfamiliar story of an incidence of social injustice, but also uncovers a lamentable tale, around the time of World War I, of political bigotry and social ostracism, born out of nationalistic hostility, partisan politicism and an undercurrent of anti-semitism a lesson to us all. The chemistry of the legal process and political intrigue that engulfed Sir Edgar Speyer and his family needs unravelling. The ultimate procedure to deprive a prominent national figure of British citizenship and his position as a Privy Councillor, along with the citizenship of his family, makes for compulsive reading. Professor Lentin displays a helpful lucidity.

That Sir Edgar, with his German heritage and youthful background (he lived in Germany until the age of 25), committed indiscretions that warranted official censure cannot be gainsaid, although, significantly, there were never any criminal proceedings for offences relating to association with, and even indirect assistance to, an enemy with whom Britain had been at war. But did those matters, which were intrinsically quite serious they were more than public indiscretions constitute disloyalty or disaffection towards the Crown? The three-man Committee of Inquiry (a High Court judge (Mr Justice Salter), a county court judge, and a prominent citizen), in a fourteen-page report made to the Home Secretary in December 1921, long after the war had ended was singularly uninformative, beyond largely rubber-stamping the Conservative-dominated Coalition Governments submissions that Sir Edgar should be deprived of British citizenship under the alien and citizenship legislation of 191418. Public opinion at the time was divided, and nothing since has pointed to a clear verdict. Professor Lentin, with conspicuous even-handedness, inclines slightly to favour a record of not proven. His authorship is all too judicious and modest. The lesson for us is to beware a process that was gravely deficient and at that time under-regulated, in two respects, by judicial review.

The Committees conclusion that Sir Edgars conduct (or misconduct, if you will) fell foul of the statutory provision of disloyalty or disaffection was a total failure to apply a legal mindset to an odd phraseology. That terminology in the British Nationality and Status of Aliens Act 1914 (as amended in 1918) survives in the same form to this day by virtue of the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002, even though the language is more than a little outdated. A more modern formula appears in the European Convention on Nationality, to which Britain is a signatory but has not ratified; Loss of affection is not enough. Nothing like that appears in the Salter Committee report of 1921. If the Committee had approached the language of Parliament seriously and considerately the same as any body would today and as the Committee should have done under the 1914/1918 Act a result favourable to Sir Edgar should have been arrived at. Judicial review today would have seen to that.

What is worse is that the Home Secretary of the day, with whom the ultimate decision lay, seems totally to have ignored the legal issue, in which he had had some advice to the contrary from a government lawyer, and adopted a stance that would not today have survived judicial scrutiny. The Committees report in its introductory paragraph recites Sir Edgars 27 years of life in England in glowing, if understated, terms: He was a very prosperous and successful man; he was the head of a great business [merchant banking]; his wealth was large; he was the friend of distinguished persons [including the Liberal Prime Minister, Mr Asquith, who publicly in 1915 had declared his confidence in Sir Edgar]; he was a munificent patron of music [he rescued Sir Henry Woods Promenade Concerts the BBC Proms from inevitable collapse]; his charitable bequests were many; he took an active and useful part in hospital management. He was created a baronet in 1906 and sworn to the Privy Council in 1909. All this conspicuous philanthropy and contribution to cultural and public life in Britain which included financing the construction of much of the London Underground was deemed irrelevant by the Committee. If rightly so, it should not have been irrelevant to the Home Secretary of the day, although if Sir Edgars intention to disaffection was the statutory test, his contributions to British cultural life were, in my view, a relevant consideration for the tribunal, and certainly for the Home Secretary. No longer a British subject, Sir Edgar automatically ceased to be a Privy Councillor. For reasons to do with official understanding about the Royal Prerogative (very differently understood today), Sir Edgar was not stripped of his baronetcy and title, although he never used the title thereafter. The Home Secretary was not obliged in the law relating to public inquiries (then or now) to accept or act in accordance with the Committees recommendation. In a House of Commons debate, the previous Home Secretary, Sir George Cave, pointed out that the final decision had to be made independently of the Committee. Sir George rightly stated: The act is the act of the Secretary of State, and not of the Committee. Peremptorily, and in a decision that would today be judicially reviewable, the Home Secretary followed internal advice that he was bound to endorse the Committees legally unreasoned verdict. He was wrong.