Table of Contents

ALSO BY PAUL JOHNSON

Modern Times: The World from the Twenties to the Nineties

A History of the Jews

The Birth of the Modern: World Society 1815-1830

Intellectuals: From Marx and Tolstoy to Sartre and Chomsky

A History of the American People

Art: A New History

George Washington: The Founding Father

Creators: From Chaucer and Drer to Picasso and Disney

Napoleon: A Penguin Life

Heroes: From Alexander the Great and Julius Caesar

to Churchill and de Gaulle

This book is dedicated

to my eldest son, Daniel

Chapter One

Young Thruster

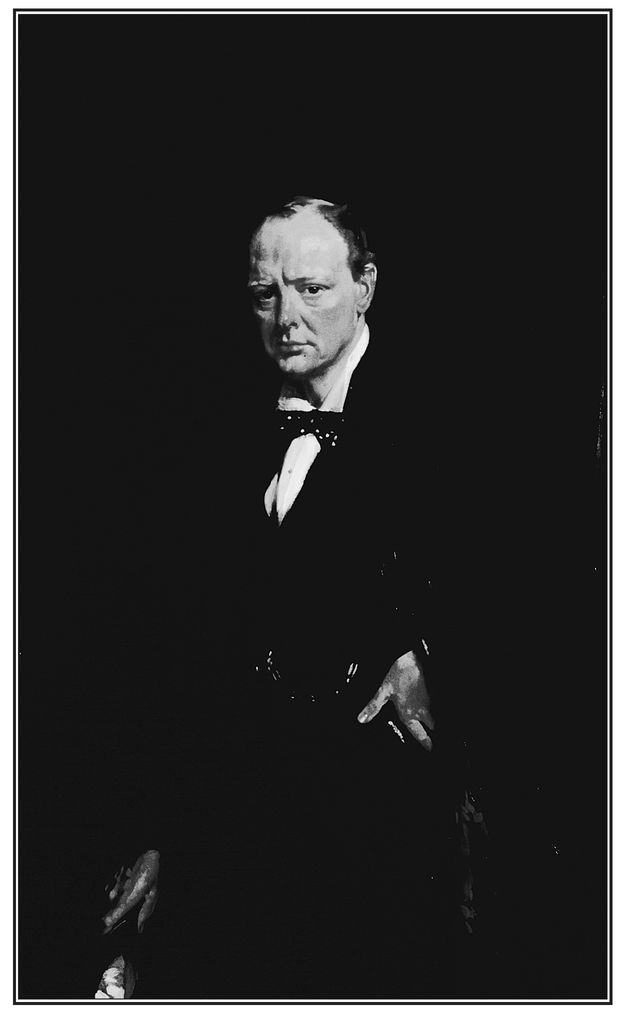

Of all the towering figures of the twentieth century, both good and evil, Winston Churchill was the most valuable to humanity, and also the most likable. It is a joy to write his life, and to read about it. None holds more lessons, especially for youth: How to use a difficult childhood. How to seize eagerly on all opportunities, physical, moral, and intellectual. How to dare greatly, to reinforce success, and to put the inevitable failures behind you. And how, while pursuing vaulting ambition with energy and relish, to cultivate also friendship, generosity, compassion, and decency.

No man did more to preserve freedom and democracy and the values we hold dear in the West. None provided more public entertainment with his dramatic ups and downs, his noble oratory, his powerful writings and sayings, his flashes of rage, and his sunbeams of wit. He took a prominent place on the public stage of his country and the world for over sixty years, and it seemed empty with his departure. Nor has anyone since combined so felicitously such a powerful variety of roles. How did one man do so much, for so long, and so effectively? As a young politician, he found himself sitting at dinner next to Violet Asquith, daughter of the then chancellor of the exchequer. Responding to her question, he announced: We are all worms. But I really think I am a glow worm. Why did he glow so ardently? Let us inquire.

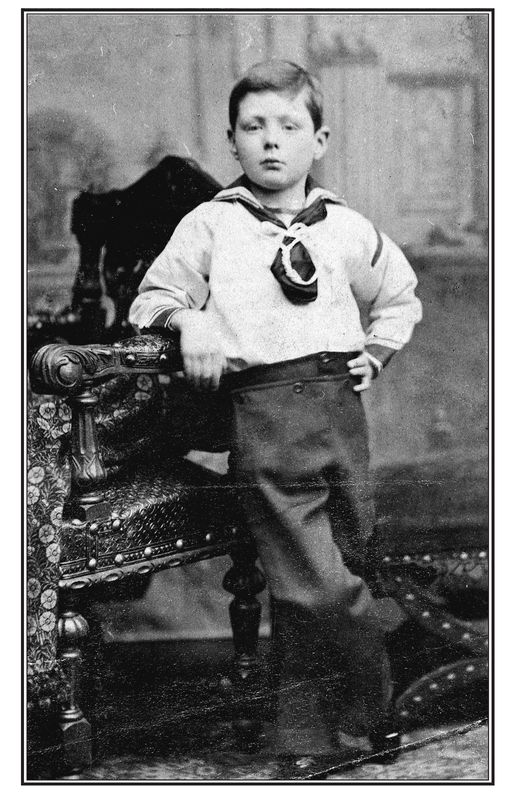

Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill was born on November 30, 1874. His parents were Lord Randolph Churchill, younger son of the 7th Duke of Marlborough, and Jennie, second of the four daughters of Leonard Jerome, financier, of Chicago and New York. The birth was due to take place in London, in a Mayfair mansion the young couple had taken, where all was prepared. But during a visit to Blenheim Palace, Lord Randolphs home, Jennie had a fall, and her child was born two months prematurely in a ground-floor bedroom at the palace, hastily got ready. Thus the characteristic note was struck: the unexpected, haste, risk, danger, and drama. The birth pangs were eight hours long and exhausting, but the child was very healthy, also wonderfully pretty. He had red hair, described as the colour of a bronze putter, fair, pink skin, and strong lungs. He later boasted that his skin was exceptionally delicate and forced him always to wear silk next to it. He claimed he had never owned or worn a pair of pajamas in his life. Like his mother, he was active and impulsive and so accident prone, but of organic disease he was little troubled for most of a long life. Though he suffered from deafness in old age, he had no disabilities other than a slight lisp (almost undetectable on recordings). For this reason he took great care of his teeth. He went to the best dentist of his time, Sir Wilfred Fish, who designed his dentures, which were made by the outstanding technician Derek Cudlipp. (They are preserved in Londons Royal College of Surgeons Museum.) He also took care of his health, appointing, as soon as he was able, a personal physician, Charles McMoran Wilson, whom he made Lord Moran (Fish was rewarded with a knighthood). Churchill also ate heartily, especially steak, sole, and oysters. He daily sipped large quantities of whiskey or brandy, heavily diluted with water or soda. Despite this, his liver, inspected after his death, was found to be as perfect as a young childs. Churchill was capable of tremendous physical and intellectual efforts, of high intensity over long periods, often with little sleep. But he had corresponding powers of relaxation, filled with a variety of pleasurable occupations, and he also had the gift of taking short naps when time permitted. Again, when possible, he spent his mornings in bed, telephoning, dictating, and receiving visitors. In 1946, when I was seventeen, I had the good fortune to ask him a question: Mr. Churchill, sir, to what do you attribute your success in life? Without pause or hesitation, he replied: Conservation of energy. Never stand up when you can sit down, and never sit down when you can lie down. He then got into his limo.

This vivacious and healthy child was the elder of two sons born to remarkable parents. The father, Lord Randolph Churchill (1849-95), was educated at Eton and Merton College, Oxford. He was MP for the family borough of Woodstock, just outside Blenheim Palace, for the decade 1874-85, and then for South Padding-ton in London until his death. His political life was meteoric, turbulent, and punctuated by spectacular rows. With a few discontented colleagues, he founded a pressure group advocating more vigorous opposition to the Liberal majority (1880-84) and espousing what he called Tory Democracy. But, asked what it stood for, he privately replied: Oh, opportunism, mostly. He also opposed Gladstones Irish Home Rule policy, which would have made Protestant Ulster submit to an all-Ireland Catholic majority, with the inflammatory slogan Ulster will fightand Ulster will be right. He was an impressive speaker, and by the mid-1880s he was one of only four politicians whose speeches the Central News Agency correspondents had orders to repeat in full, the other three being Glad-stone himself, Lord Salisbury, the Tory leader, and the dynamic radical-imperialist Joseph Chamberlain. The years 1885-86 marked the apex of Lord Randolphs career. He was first secretary of state for India, and then for six months chancellor of the exchequer. But while preparing his first budget he had a deadly row over spending with the prime minister. Salisbury was supported by the rest of the cabinet, and Lord Randolph resigned, discovering in the process that he had grotesquely overplayed his hand. It was a case of the dog barking but the caravan moving on. He never recovered from this mistake. At the same time, a mysterious and progressive illness began to affect him. Some believed it was syphilis, others a form of mental corrosion inherited from his mothers branch of the family, the Londonderrys. Gradually his speeches became confused and halting and painful to listen to, until death in 1895 drew a merciful curtain over his shattered career. Winston was only twenty when his father died, and was haunted by this tragic final phase until he exorcised the ghost by writing a magnificent two-volume biography, transforming his father into one of the great tragic figures of English political history. It was a further source of unhappiness for Winston that he had seen so little of his father, first so busy, then so stricken. He remembered every word of the few personal conversations he had had with him.