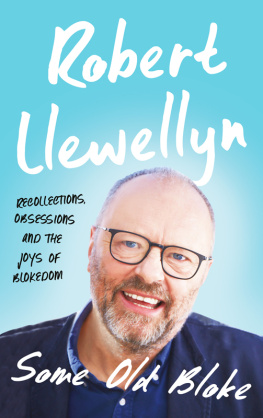

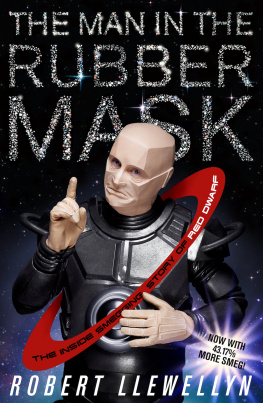

Robert Llewellyn is an actor, novelist, screenwriter, comedian and TV presenter, best known for Red Dwarf , Scrapheap Challenge , Carpool and Fully Charged . He drives an electric car and writes under a rack of solar panels in Gloucestershire.

By the Same Author

The Reconstructed Heart

The Man in the Rubber Mask

Thin He Was and Filthy-Haired

Therapy and How to Avoid It (with Nigel Planer)

The Man on Platform 5

Punchbag

Sudden Wealth

Brother Nature

Behind the Scenes at Scrapheap Challenge

Sold Out

News from Gardenia

News from the Squares

News from the Clouds

For Reg and Brenda

Contents

The Plaque

Early one morning in May 2013 I received a text from the comedian Ross Noble.

Ross is a lovely fellow and he wanted me to be on his telly programme, although this flattering request was imbued with a microdot of low-status subtext.

This was very much a last-minute thing. He wanted me on his show but not later in the year or three months ahead as might be expected with a traditional TV production.

No, he wanted me to be there that day.

The text from Ross had an air of panic about it: they couldnt get any properly famous celebrity at such short notice, so they tried me.

Im not suggesting that Im under constant pressure to make public appearances, but I can, occasionally, be quite busy.

On the morning I got the text from Ross I was under enormous pressure to feed the chickens and put the rubbish out, so I replied, Yes.

Then I looked in the bathroom mirror.

The slightly backlit reflection confirmed that I was (then) a fifty-seven-year-old bloke, and while that could be and often is a depressing realisation, on this particular morning I was gently elated at how lucky Id been.

Id been around the block a bit, but Id never spent a night in a hospital, never had to wear a uniform or fight in a war.

Id never been challenged to survive a post-apocalyptic Armageddon, zombie apocalypse or a tsunami; I hadnt experienced starvation or been put in prison for my opinions; I hadnt been oppressed or brutalised because of my gender or the colour of my skin.

If, as the writer and doctor Abraham Verghese argues, geography is destiny, then Ive been lucky from the get-go.

Of Indian heritage, Verghese was born in Ethiopia, had to flee the civil war when he was a kid, and went to America with his family. There he studied medicine, worked as a doctor in India, went back to America and became a writer.

His destiny was very much defined by geography; he is part of the massive diaspora of many people around the world.

I didnt have any of that. Im a white-skinned bloke born in a European country where my antecedents had been living for, who knows, possibly thousands of years.

However, the acknowledgement of coming from where I do, being my age and acknowledging my privilege is, I will argue, very important.

Its a political stance and it seems quite rare among my peers.

There are many men living in developed Western countries the same age as me who, it would seem, feel hard done by. They might express this disappointment through fake jocularity to disguise the fury and frustration they feel inside.

A certain Mr Farage is a good example.

Miserable, moaning, self-pitying whingers who still see the world as their grandfathers would have done. Being British and proud to wave a flag. Lamenting the passing of our world-power status, wasting a fortune on nuclear weapons, the list goes on. Men my age.

No, I dont want to be a miserable old bloke. Blaming other people for everything, puffed up and pompous, bullying and pig ignorant.

In contrast to this miserable anger, and I say this with some pride, I acknowledge that I have been lucky.

For a start Im still alive and I can walk, bend down and pick things up okay, that activity involves a bit of grunting but I can still do it.

Im also lucky because Im a white man living in Europe, as opposed to, say, a black woman living in Somalia or an old Indian man living in Maharashtra begging for food at a dusty train station.

Sure, my life has been tough at times. Ive cried myself to sleep on occasion, Ive had disappointments, humiliations and failures, but they have generally turned out to be my own fault.

A plus to the six decades under my expanded belt is that Ive learned a few useful things along the way, quite a bit about gearboxes, laundry, transmission systems, the importance of equality between genders, single socks, brake callipers, tolerance of people different from myself, vegetable gardening, parenting, hydraulic diggers, love, baking cakes, limited slip differentials, reading my children bedtime stories, asynchronous electric motors, self-awareness, building bonfires, battery-management software, bed-making and one or two things about being a bloke.

For the last few years I have been trying to reclaim the word bloke. Its a very common word in both the UK and Australia. For me, it denotes a man in late middle age, a bit knackered, a bit broken down by life, but still willing to get stuck in.

Commonly used terms such as good bloke or a nice bloke indicate its generally a positive term.

Being a bloke is a great privilege and should be recognised as such by those who have had blokedom bestowed upon them.

If you are male and live long enough, you can be fairly certain that at some stage in the latter portion of your life, you will have blokedom so bestowed.

The generally accepted idea is that a male baby gradually develops into a boy, then into a teenager or adolescent and then at some point you sort of become a man.

Eventually.

It takes a while.

In fact it seems to be taking longer and longer.

My grandfathers generation went to school until they were about twelve and then became adults. Bosh. Just like that.

A thirteen-year-old apprentice dressed the same way as adults. They had jobs and apparently didnt think any more about it.

My fathers generation went to school a little bit longer but then became adults immediately after they left their education, an elite minority going to university, the overwhelming majority into the armed forces or a full-time job.

The armed forces were a big thing for both my father and grandfather. My paternal grandfather Percy fought in the First World War, lost an eye but somehow survived.

My father Reginald fought in the Second World War, flew Halifax and Wellington bombers on thirty-six missions over occupied Europe and survived.

The pressure on them to be adults at a very early age is pretty much impossible for us to imagine now, but it was clearly concrete and insurmountable at the time.

I can now see I was an adolescent-man well into my mid-thirties. I wasnt mature. I didnt conform to any of the traditional male roles that were laid down for me during my education.

You could call this deliberately fostered immaturity and I was fully aware of the fact. I articulated it at the time. I didnt want to grow up and be an adult because all the role models I saw of grown-up adult men seemed to me to be rather negative.

Grown-ups, proper men, men who wore suits or uniforms always seemed a bit bitter, cynical, sexist, racist, homophobic and managed to consistently blame others for what appeared to me to be their own failings.

I didnt want to be like that so I decided to stay an adolescent.

I maintain that there were positive elements to this determination. It helped me keep a fresh and open attitude to the world and, most importantly, to people who werent like me.

Next page