Acknowledgments are due to the following people. Without their help, I would not have got this far:

My wife Josephine and my children, the Rev. Father Rudolf OP, the Rev. Konrad and Dora, who all supplied thoughtful comments and helpful ideas. I hope Konrad will feel he was successful in his worthwhile endeavours to have the book shorn of its more questionable comments.

I discussed the book with some of my great friends who have known me well over the last sixty years, especially John Bellingham, Michael Dormer and Lord Moyne.

Philip Dodd, for his encouragement and assistance in setting down these memories.

Guy Sainty and Don Victor Franco de Baux for their invaluable advice on the genealogy and ancestry of my family.

For their support and organisation: Dee Anstice, Jules Kopec, Pandora Millen, Jim Pfenninger and Sally Renny.

For their help in exploring the photographs in the family archive: Emily Hedges and Laurence Hill.

Gerrit te Spenke and Jan Favie, for their helpful comments.

Ian Shackleton at the Chatham Archive, Christopher Sykes and Alan Williams, for their assistance.

The publishing team at Bloomsbury, for their encouragement, especially Nigel Newton, Michael Fishwick and Anna Simpson.

Last, I must thank the Rolling Stones for the years we voyaged together through waters often uncharted, occasionally choppy, but always enthralling.

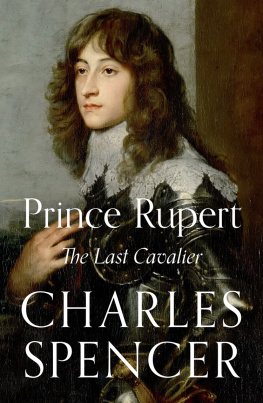

The Loewenstein-Wertheim family is the senior branch of one of Europes oldest reigning families. It not only produced ruling Dukes, then Electors and Kings of Bavaria, but two Holy Roman Emperors, the first King of independent Greece, Electors of the Palatinate, Kings of Sweden, Hungary, Norway and Denmark and two anti-Kings of Bohemia, who challenged the Habsburg kings in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

They also inherited the Duchies of Julich and Berg which straddle what is now the German-Dutch border, the Counties of Holland, Hainault and Zeeland in what is now a large part of the Netherlands and Belgium as well as other smaller German states. The family produced a notable branch of the British royal family, of which Prince Rupert of the Rhine, Duke of Cumberland, is the best-known member, and a branch of the Spanish royal family (in the twentieth century). The Loewensteins themselves were minor sovereigns as rulers of the immediate County of Wertheim and other smaller territories held as fiefs of the Empire.

Bavaria, the Palatinate and the County of Wertheim were all states of the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation, founded on Christmas Day 800 when Pope Leo III crowned Charlemagne Imperator Romanorum . In 1512, this was formally titled the Imperium Romanum Sacrum Nationis Germanic (translated in German as the Heiliges Rmisches Reich Deutscher Nation ), or Holy Roman Empire, which is how this strange construct has been known to history and which was famously dismissed by Voltaire as being neither Holy, nor Roman nor an Empire.

In 1362 the right to elect the Emperor was defined and limited to seven ruling princes, three ecclesiastical the Archbishops of Mainz, Trier and Cologne and four lay: the King of Bohemia (who although an elector was otherwise excluded from the affairs of the Empire), the Count Palatine of the Rhine (Wittelsbach), the Duke of Saxony (Wettin) and the Margrave of Brandenburg (Hohenzollern). These were later augmented by the elevation of Bavaria and the Duchy of Brunswick-Lneburg (as Hannover) to Electorates.

The Dukes, Margraves, Landgraves, Princes, and Imperial Counts, Barons and Knights, as well as the ecclesiasts who held immediate territories, all enjoyed membership in the Imperial Diet, a kind of supra-national Parliament for the German states. This included the sovereigns of the larger territories such as Saxony, Bavaria and Brandenburg as well as the rulers of quite modest territories, or representatives of groups of statelets along with the Archbishops, Bishops, Abbots and Abbesses who ruled the ecclesiastical states. Considerable prestige became attached to possession of even a relatively modest immediate territory, some having only a few hundred inhabitants, and it was a measure of the standing of the Loewensteins that they remained immediate sovereigns until the Empires dissolution in 1806.

The Loewenstein family descends from Berthold, Margrave in Bavaria, who died in 980 and whose probable grandson, Otto, acquired the castle and county of Scheyern, exchanged for that of Wittlesbach, a small township north of Munich, by the latters son Otto II, in 1119. In 1214 the family also acquired the enormously wealthy County Palatine of the Rhine in 1214 and the duchy of Bavaria was ceded to a junior line. When the senior, Palatine, line became extinct in 1777 Bavaria and the Palatinate with the familys others possessions were combined into one state. In 1805, after an agreement with the French by which certain of the familys possessions along the left bank of the Rhine were ceded to Napoleon, Bavaria became a kingdom, remaining such until 1918 when the family finally ceased to reign.

The origins of the Loewenstein (in German, Lwenstein) branch go back to the marriage of Elector Palatine Friedrich I, who had become Elector on the death of his elder brother Ludwig IV, mortally wounded in battle in 1449 at the age of twenty-five. As he lay dying Ludwig commanded his brother Friedrich to support his young son Philip as his youth necessitated a regency. Since a regency may have required imperial permission, Friedrich instead assumed the title of Elector under the terms of an Arrogation in which he undertook not to marry and, although the Emperor tried to intervene, Friedrich proved an adept ruler whose victory over the imperial allies at the Battle of Seckenheim in 1462 secured his own rule and possession of the Palatinate for his nephew, whom he had formally adopted in 1451.

Friedrich, however, wanted to marry his long-term mistress, Klara Tott (otherwise known as Klara Dettin), who had already given birth to their two sons a decade earlier; she was a former maid of honour at the Munich court and the daughter of an Augsburg burgher but not considered of suitably elevated rank to be the bride of a sovereign ruler. Philip, by then aged twenty-one, wanted to protect his own inheritance but nonetheless agreed that the earlier Arrogation should be varied to permit his uncles marriage, while excluding Friedrichs descendants from succeeding as ruler.

Friedrich married sometime before October 1471 with his nephews consent and, on 24 January 1472, renounced his succession rights to the Palatinate for himself, his wife and their descendants. Friedrich and Klaras marriage served to legitimise them under canon law, since neither was under any legal impediment to marry once Philip had given his consent; furthermore, their two sons had already been legitimatised by bulls issued by both the Pope and the Bishop of Speyer before 14 October 1470.

The future Elector Philip must have recognised that he ultimately owed his throne to his uncle Friedrich, and it would have been ungracious for him to have withheld consent, particularly since Friedrich had not only defended his existing inheritance but had managed to enlarge it. Klaras elder son Friedrich, who died aged thirteen in 1474, and Louis (14631524), were accorded several properties and substantial sums but Friedrich died on 12 December 1475 before the grant of further estates could be effected.

Philip initially only allowed Ludwig, Friedrichs surviving son, the lordship of Scharffeneck (in 1476) and the County of Loewenstein (in 1488) but then, in 1490, granted his cousin the lordships of Abstatt and castle Wildeck and in 1494 asked the Emperor, Maximilian I, to raise Ludwig to the rank of Count of the Empire as Count of Loewenstein. Of Ludwigs five sons, only the youngest, Friedrich (150241), left descendants, of whom the elder, Wolfgang (152771), left an only son, Wolfgang II (155596), who received the lordship of Scharffeneck and was known as the Count of Loewenstein-Scharffeneck; this branch became extinct in 1633 when the property reverted to the junior Loewenstein line.

Next page