PENGUIN MODERN CLASSICS

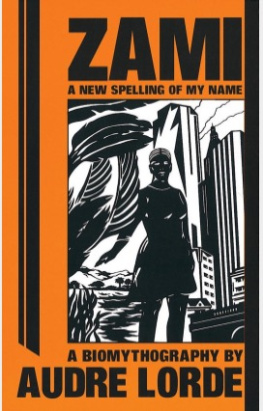

ZAMI: A NEW SPELLING OF MY NAME

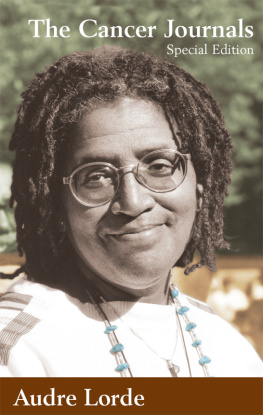

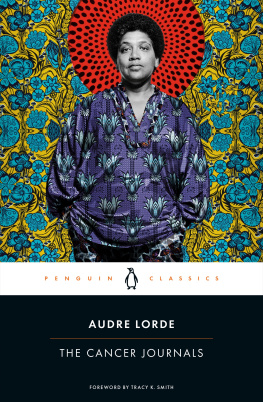

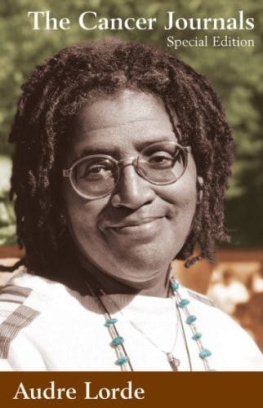

Audre Lorde was a writer, feminist and civil rights activist or, as she famously put it, Black, lesbian, mother, warrior, poet. Born in New York in 1934, she had her first poem published while she was still in high school. After stints as a factory worker, ghost-writer, social worker, X-ray technician, medical clerk and arts and crafts supervisor, she became a librarian in Manhattan and gradually rose to prominence as a poet, essayist and speaker, anthologized by Langston Hughes, lauded by Adrienne Rich and befriended by James Baldwin. She was made Poet Laureate of New York State in 1991, when she was awarded the Walt Whitman prize; she was also awarded honorary doctorates from Hunter, Oberlin and Haverford colleges. She died of cancer in 1992, aged 58.

CHAPTER 1

Years later, as partial requirement for a degree in library science, I did a detailed comparison of atlases, their merits and particular strengths. I used, as one of the foci of my project, the isle of Carriacou. It appeared only once, in the Atlas of the Encyclopedia Britannica, which has always prided itself upon the accurate cartology of its colonies. I was twenty-six years old before I found Carriacou upon a map.

Audre Lorde

ZAMI: A NEW SPELLING OF MY NAME

A Biomythography

PENGUIN CLASSICS

UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia

India | New Zealand | South Africa

Penguin Books is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com.

First published in the United States of America by Persephone Press 1982

First published in Penguin Classics 2018

Copyright Audre Lorde, 1982

The moral right of the author has been asserted

Cover: Revolutionary Sister by Dindga McCannon, 1971

(Mixed media construction on wood)

Dindga McCannon/Brooklyn Museum

ISBN: 978-0-241-35109-3

To Helen, who made up the best adventures

To Blanche, with whom I lived many of them

To the hands of Afrekete

In the recognition of loving lies an answer to despair.

1

Grenadians and Barbadians walk like African peoples. Trinidadians do not.

When I visited Grenada I saw the root of my mothers powers walking through the streets. I thought, this is the country of my foremothers, my forebearing mothers, those Black island women who defined themselves by what they did. Island women make good wives; whatever happens, theyve seen worse. There is a softer edge of African sharpness upon these women, and they swing through the rain-warm streets with an arrogant gentleness that I remember in strength and vulnerability.

My mother and father came to this country in 1924, when she was twenty-seven years old and he was twenty-six. They had been married a year. She lied about her age in immigration because her sisters who were here already had written her that americans wanted strong young women to work for them, and Linda was afraid she was too old to get work. Wasnt she already an old maid at home when she had finally gotten married?

My father got a job as a laborer in the old Waldorf Astoria, on the site where the Empire State Building now stands, and my mother worked there as a chambermaid. The hotel closed for demolition, and she went to work as a scullery maid in a teashop on Columbus Avenue and 99th Street. She went to work before dawn, and worked twelve hours a day, seven days a week, with no time off. The owner told my mother that she ought to be glad to have the job, since ordinarily the establishment didnt hire spanish girls. Had the owner known Linda was Black, she would never have been hired at all. In the winter of 1928, my mother developed pleurisy and almost died. While my mother was still sick, my father went to collect her uniforms from the teahouse to wash them. When the owner saw him, he realized my mother was Black and fired her on the spot.

In October 1929, the first baby came and the stockmarket fell, and my parents dream of going home receded into the background. Little secret sparks of it were kept alive for years by my mothers search for tropical fruits under the bridge, and her burning of kerosene lamps, by her treadle-machine and her fried bananas and her love of fish and the sea. Trapped. There was so little that she really knew about the strangers country. How the electricity worked. The nearest church. Where the Free Milk Fund for Babies handouts occurred, and at what time even though we were not allowed to drink charity.

She knew about bundling up against the wicked cold. She knew about Paradise Plums hard, oval candies, cherry-red on one side, pineapple-yellow on the other. She knew which West Indian markets along Lenox Avenue carried them in tilt-back glass jars on the countertops. She knew how desirable Paradise Plums were to sweet-starved little children, and how important in maintaining discipline on long shopping journeys. She knew exactly how many of the imported goodies could be sucked and rolled around in the mouth before the wicked gum arabic with its acidic british teeth cut through the tongues pink coat and raised little red pimples.

She knew about mixing oils for bruises and rashes, and about disposing of all toenail clippings and hair from the comb. About burning candles before All Souls Day to keep the soucoyants away, lest they suck the blood of her babies. She knew about blessing the food and yourself before eating, and about saying prayers before going to sleep.

She taught us one to the mother that I never learned in school.

Remember, oh most gracious Virgin Mary, that never was it known that anyone who fled to thy protection, implored thy help, or sought thy intercession, was ever left unaided. Inspired with this confidence I fly unto thee now, oh my sweet mother, to thee I come, before thee I stand, sinful and sorrowful. Oh mother of the word incarnate, despise not my petitions but in thy clemency and mercy oh hear and answer me now.

As a child, I remember often hearing my mother mouth these words softly, just below her breath, as she faced some new crisis or disaster the icebox door breaking, the electricity being shut off, my sister gashing open her mouth on borrowed skates.

My childs ears heard the words and pondered the mysteries of this mother to whom my solid and austere mother could whisper such beautiful words.

And finally, my mother knew how to frighten children into behaving in public. She knew how to pretend that the only food left in the house was actually a meal of choice, carefully planned.

She knew how to make virtues out of necessities.

Linda missed the bashing of the waves against the sea-wall at the foot of Noels Hill, the humped and mysterious slope of Marquis Island rising up from the water a half-mile off-shore. She missed the swift-flying bananaquits and the trees and the rank smell of the tree-ferns lining the road downhill into Grenville Town. She missed the music that did not have to be listened to because it was always around. Most of all, she missed the Sunday-long boat trips that took her to Aunt Annis in Carriacou.

Everybody in Grenada had a song for everything. There was a song for the tobacco shop which was part of the general store, which Linda had managed from the time she was seventeen.