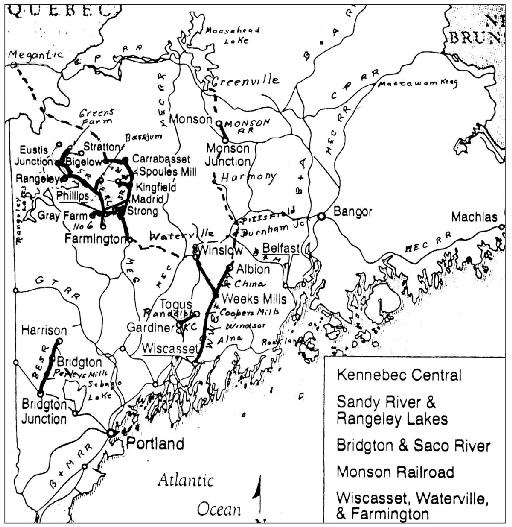

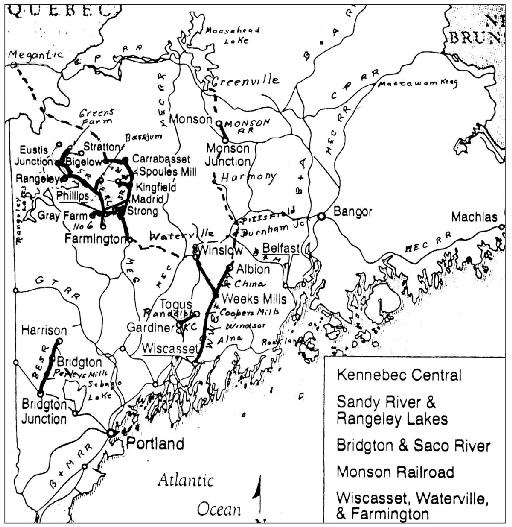

This map represents Maine narrow-gauge railroads at their peak c. 1915. The heavy lines indicate the two-foot railroads at that time. Standard-gauge railroads are shown with the light lines, and the broken lines show the proposed narrow-gauge extensions.

Maine Narrow Gauge Railroads

Robert L. MacDonald

Copyright 2003 by Robert L. MacDonald

9781439628676

Published by Arcadia Publishing

Charleston, South Carolina

Printed in the United States of America

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 2003100244

For all general information contact Arcadia Publishing at:

Telephone 843-853-2070

Fax 843-853-0044

E-mail sales@arcadiapublishing.com

For customer service and orders:

Toll-Free 1-888-313-2665

Visit us on the Internet at www.arcadiapublishing.com

The Maine Narrow Gauge Railroad Company and Museums official logo is featured on patches, badges, newsletters, and other materials provided for members and guests. It illustrates a front-end view of an early rear-tank-type engine. The Portland Company constructed eight of these for use on Maine two-foot-gauge railroads. They were the last steam railroad locomotives of any gauge built by the Portland Company, which a century later became the site for survivors of the Maine narrow-gauge era.

Table of Contents

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Most of the material used in this book came from the authors collection of photographs and memorabilia gathered over 60 years. However, some came from the archives of the Maine Narrow Gauge Railroad Company and Museum and from its various members. Where borrowed items are involved from other sources, these are credited accordingly. In some instances, even though pictures have been in the authors possession for several decades, the name of the photographer is noted where that information is known.

All the two-foot-gauge operating railroads and museums in Maine are dependent on volunteers. Throughout the text, reference is made to these splendid endeavors in behalf of keeping alive Maines narrow-gauge heritage. The Maine Narrow Gauge Railroad Company and Museum, located on Fore Street in Portland, is an especially ambitious project initiated in the fall of 1992 by Phineas Sprague Jr. with attorney Edward Ashley and trucker Erving Bickford. Through their efforts and the efforts of hundreds of volunteers and supporters, it became possible for the return to Maine of many authentic Maine two-foot-gauge engines and cars from the old Edaville Railroad after it shut down in 1991 and faced foreclosure. There is a great spirit of cooperation and sharing among the various museums dedicated to the work of restoring and preserving Maine two-foot-gauge relics.

The author is deeply grateful to those who were initially responsible for saving equipment from being dismantled, including Ellis D. Atwood, Edgar Mead, Van Walsh, John Holt, Eric Sexton, the Ramsdells, and others. There were many people who saved car bodies from being junked when lines were abandoned; the bodies were later salvaged, making possible their eventual restoration for public enjoyment. This book is dedicated to all of these people and to those actively involved today in preserving Maines narrow-gauge heritage.

INTRODUCTION

Track gauges (the distance between rails), established for the movement of railway equipment over various track routes, may be as varied as their geographical locations. As to what may be recognized as standard, between broad and narrow, is relative to what is most commonly used in a particular locality. In North America, the earliest railroads were usually patterned after those in the United Kingdom. Especially in Wales, the necessity to move minerals in wagons from mines to ports for reshipment by water resulted in the application of iron tracks for ease of movement in the early years of the 19th century. Prior to this, the wagons followed ruts in the roads, reputed to have been established centuries earlier by Roman chariots. These rut-spaced wheels ultimately became the standard for most railroad construction in Great Britain. Since the earliest locomotives used in North America were of British manufacture, the gauge of four feet eight and one-half inches also became an American standard.

Because of the exceptionally rugged terrain in the western part of Wales, where slate mining flourished, a greater flexibility was needed, which was provided by a much smaller gauge of a mere 60 centimeters (approximately two feet). One such pioneer narrow gauge was the Festiniog Railway between Portmadoc and Blaenau Festiniog. Originally, wagons were gravity propelled downhill with outbound ladings and were horse drawn light on the return upward movement to the mines. After the Festiniog became steam operated in the late 1860s, passenger service was introduced. At that time, the efficiencies realized of using narrow gauge on the Festiniog gained worldwide attention from potential builders of short lines in areas that larger systems had bypassed. After the American Civil War, the explosion of railroad construction in America excluded many isolated localities, which led to widespread interest in use of narrower gauges.

Most American railroad promoters and engineers, after visiting the Festiniog and observing the advantages of narrow gauge over standard, adopted a three-foot gauge as most practical, rather than the two-foot gauge. One such American promoter, George E. Mansfield, from Massachusetts, thought otherwise. He was the first to develop a two-foot-gauge system for American railroads. With his pioneer Billerica & Bedford Railroad of Massachusetts was introduced an entirely new concept of narrowness for common carrier railroad use. The standards developed for his two-foot-gauge experiment were found practical for the times and continued to be used for over 50 years at several locations in the state of Maine. Not until the spread of highway motor carriers in the 1920s and 1930s was the narrow gauge rendered virtually obsolete. However, the failure of his Billerica & Bedford Railroad came in just six months (between 1877 and 1878) as the result of impatient creditors not allowing enough time for business to develop. Its proven efficiencies, nevertheless, were not lost to interested visitors from Franklin County.

The equipment became the initial rolling stock for a narrow-gauge Sandy River Railroad between Farmington and Phillips in 1879. This Sandy River was the first of nearly a dozen such lines in various parts of Maineplus scores of others proposed. These were not just industrial operations (there were many of these) but were recognized common carriers, which conducted their business subject to the same supervision and regulations of their wider counterparts. They transported passengers, mail, express, and freight of all kinds.

Between 1979 and 1943, the various Maine two-footers gradually succumbed to highway competition and were abandoned and dismantled. Unfortunately, they ended their days during the Great Depression, and little survived in way of equipment and rolling stock for the interest of posterity. However, thanks to a wealthy cranberry grower in South Carver, Massachusetts, Ellis D. Atwood, the preservation of remaining surviving Maine two-foot-gauge equipment became a possibility after 1941. Even while the salvage company was dismantling the 16-mile Bridgton & Harrison Railway in September 1941, Atwood made his move to purchase all the rolling stock for use on his cranberry plantation. Unfortunately, World War II prevented him from having his narrow-gauge treasures being transported. With the ending of hostilities in late 1945, Atwood began moving not only the Bridgton & Harrison equipment but also any other surviving two-foot-gauge relics he could acquire from different parts of Maine. Tragically, he died after an oil burner explosion in late 1950. His Edaville Railroad continued under different managements for many years until late 1991, when bankruptcy closed it down.

Next page