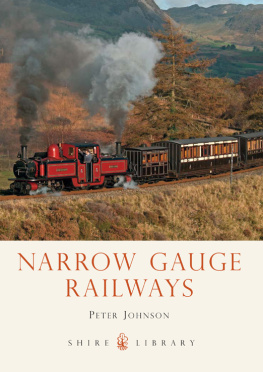

NARROW GAUGE RAILWAYS

Peter Johnson

Vale of Rheidol Light Railway Davies & Metcalfe 2-6-2T No 1 Edward VII at Capel Bangor. Specialising in steam injectors, Davies & Metcalfe built only the two Vale of Rheidol locomotives.

SHIRE PUBLICATIONS

A feature of the Rheidol valley enjoyed by passengers on theVale of Rheidol Light Railway is the lead-mine spoil that has poisoned the ground in the shape of a stag.

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

N ARROW GAUGE RAILWAYS , where the rails are closer together than those used on main lines, were first used in mines and quarries, where the tracks could reach into confined spaces and the wagons were small enough to be pushed by men or pulled by ponies. They were cheaper to build, cuttings and embankments were smaller, and curves could be sharper so they could follow the contours of the land more easily. In industry these railways could be very short: sometimes as little as 100 feet long.

As the demand for railways grew during the mid-nineteenth century, the dispute over the adoption of a standard gauge (4 feet 8 inches versus Brunels broad gauge, 7 feet inch) hindered the adoption of narrower gauges to serve mountainous or sparsely populated areas. The 1846 Gauge of Railways Act expressly forbade the construction of any railway for the carriage of passengers on any gauge other than standard.

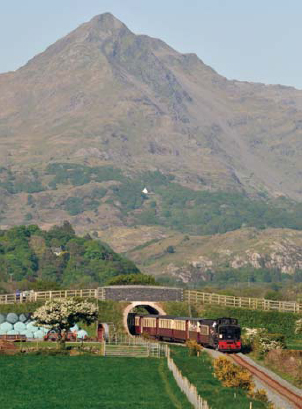

Cnicht, known as the Welsh Matterhorn in Victorian times, dominates the view as this Welsh Highland Railway train approaches Porthmadog on its journey from Caernarfon.

The realisation that standard gauge could not meet all requirements brought some measure of relaxation to its mandated use, however. In Wales, the spiritual home of narrow gauge railways, the Talyllyn Railways 1865 Act was the first to permit a sub-standard gauge (2 feet 3 inches) for the carriage of passengers, and the Festiniog Railway, further north, became the first narrow gauge railway to carry them officially. The Festiniog Railways success which occurred mainly because it had a monopoly of the slate traffic, not just because it was cheap to build and operate was responsible for the evangelical promotion of narrow gauge railways around the world.

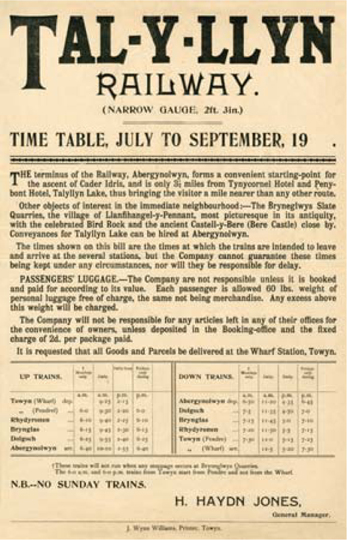

Poster published after Henry Haydn Jones took over the Bryneglwys slate quarries and the Talyllyn Railway in 1911. A blank was left in the date so that it could be used in any year. Another, similar, poster was issued in the 1920s.

There was no standard narrow gauge: there was originally no need for one. The variants around 2 feet usually had their origins in man- or animal-worked tramways in mines or quarries, while engineers were to conclude that a gauge of 2 feet 6 inches or 3 feet struck a better balance between the cost of construction and capacity.

Narrow gauge should not be considered synonymous with small, for capacity is a factor of loading gauge (the maximum size that rolling stock can be in order to get through tunnels and bridges safely), rather than the gauge of the tracks themselves: the 2-foot-gauge Festiniog Railway stock is larger than that of the 2-foot 3-inch-gauge Talyllyn Railway; and the 2-foot-gauge stock in use on the Welsh Highland Railway is too large for the Festiniog. Regardless of their gauge, railways in the United Kingdom required an Act of Parliament or a Light Railway Order before they could carry passengers. Exceptions were those built on private property, like the 2-foot 7-inch-gauge Snowdon Mountain Railway or the 3-foot-gauge Rye & Camber Tramway.

Few narrow gauge railways made any money for their shareholders, and to a greater or lesser extent they all suffered in the Depression after the First World War, and from competition from motor transport; few of them outlasted the 1930s. The Talyllyn Railway was one of those that did, but it was badly run down. At a time when many traditional industries were struggling to survive, the threat to the Talyllyn Railway when its owner died in 1950 was sufficient to set in motion the events that led to its preservation and the establishment of the railway preservation movement.

Since 1951 most of these narrow gauge railways have found new lives carrying tourists. Their success has encouraged both the construction of new railways to serve parks and zoos and the adaptation of disused standard gauge railway trackbeds for new narrow gauge lines. Some individuals have even built narrow gauge railways in farms or gardens for their own amusement. The restricted space available in this book, however, allows only the classic narrow gauge passenger-carrying railways 2-foot gauge and greater which existed before 1951, to be covered.

Double Fairlie Merddin Emrys (built in 1879) and a vintage train on a quiet October day at Tan y Bwlch, 7 miles from Porthmadog.

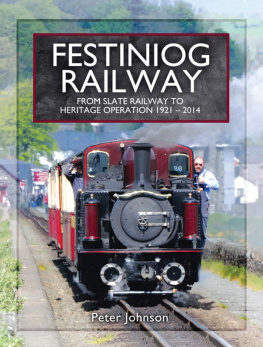

THE FESTINIOG RAILWAY

T HE FESTINIOG RAILWAY is the pre-eminent narrow gauge railway. It gained and has maintained an international reputation for innovation, particularly in its use of articulated locomotives and bogie carriages. Built under an 1832 statute and opened in 1836, its function was the carriage of slate from quarries at Blaenau Ffestiniog, in the old county of Merioneth, to the harbour at Port Madock (now Porthmadog, via Portmadoc), in Carnarvonshire, a distance of 13 miles. It is the oldest un-amalgamated railway company in the world. Its name was given to it by Act of Parliament at a time when spellings nof Welsh place names had not been standardised and when English versions were often used. Today, for marketing purposes, the form Ffestiniog Railway is usually used. The original spelling is used in this book.

Construction of mills and workers houses that accompanied the Industrial Revolution created a huge demand for roofing slate. Before the railway, pack animals had carried the slate to wharves on the river Dwyryd, where it was transhipped into river craft for carriage to coastal shipping in deeper water. Use of the river limited the time when slate could be shipped to the spring tides, in alternate weeks, when the weather was fine. The 13s 3d per ton that it cost to transport the slate to the sea was almost double the cost of production, and if it were bound for London then it would cost an additional 1 per ton.

The railway was built at the instigation of quarry owner Samuel Holland and Dublin businessman Henry Archer. The route was surveyed by James Spooner and he and Archer supervised construction. Over the 13 miles the railway descended 720 feet to the port, with an average gradient of 1 in 79, which enabled loaded wagons to descend by gravity. Horses were used to haul the empty wagons back to the quarries.

The gauge is 1 foot 11 inches, but 2 feet is convenient shorthand. Features of the line were the use of dry-stone embankments, to reduce the amount of land required, and routing it along the top of the embankment across the mouth of the river Glaslyn. William Alexander Madocks, the MP for Boston, Lincolnshire, and owner of property on the Glaslyn estuary, had built the embankment (nearly a mile long, and completed in 1812) to reclaim estuarial land. Cei Mawr embankment, 4 miles from Porthmadog, is 62 feet high, the largest of its type in Europe.