Contents

Madhur Jaffrey

Madhur Jaffrey is the author of many previous cookbookssix of which have won the James Beard Awardand was named to the Whos Who of Food and Beverage in America by the James Beard Foundation. She is also an award-winning actress with numerous major motion pictures to her credit. She lives in New York City.

Madhur Jaffrey is represented by Penguin Random House Speakers Bureau (www.prhspeakers.com).

A LSO BY M ADHUR J AFFREY

An Invitation to Indian Cooking

Madhur Jaffreys World-of-the-East Vegetarian Cooking

Madhur Jaffreys Indian Cooking

A Taste of India

Madhur Jaffreys Cookbook

Madhur Jaffreys Far Eastern Cookery

A Taste of the Far East

Madhur Jaffreys Spice Kitchen

Flavors of India

Madhur Jaffreys World Vegetarian

Step-by-Step Cooking

Quick and Easy Indian Cooking

From Curries to Kebabs

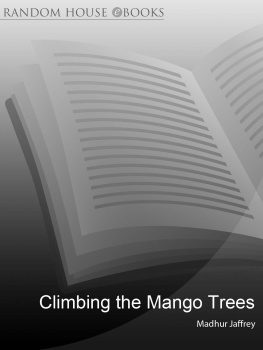

Climbing the Mango Trees

At Home with Madhur Jaffrey

Vegetarian India

FOR CHILDREN

Seasons of Splendour

Market Days

Robi Dobi: The Marvellous Adventures of an Indian Elephant

Tandoori Chicken in Delhi:

Partition and the Creation of Indian Food

from Climbing the Mango Trees

Madhur Jaffrey

A Vintage Short

Vintage Books

A Division of Penguin Random House LLC

New York

Copyright 2007 by Madhur Jaffrey

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Vintage Books, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York, and in Canada by Random House of Canada, a division of Penguin Random House of Canada Ltd., Toronto. Originally published in hardcover in Great Britain as a part of Climbing the Mango Trees by Ebury Publishing, an imprint of The Random House Group Ltd., London, in 2005, and subsequently in hardcover in slightly different form in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York, in 2006.

Vintage and colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

The Cataloging-in-Publication Data for Climbing the Mango Trees is available from the Library of Congress.

Vintage eShort ISBN9781101972588

Cover design by Perry Delavega

www.vintagebooks.com

v4.1

a

Contents

T here were other changes in the air. World War II was finally over. Whereas Europe and East Asia looked forward to peace, India could look forward only to a wrenching partition. Partition, as it was called, with a fearsome capital P. This Solomon-testing breakup of its being into two entities had already caused mayhem. The British, with Lord Mountbatten as their viceroy in India, were granting India its freedom, but not before splitting the country, taking two chunky ribs out of India to form Muslim Pakistan to its east and its west. All the secular dreams of nationalists like Jawaharlal Nehru and Mahatma Gandhi that saw Hindus, Muslims, Sikhs, and Christians coexisting in a newly independent nation were being crushed into the ground.

The Partition drama was being played out at all levels. The Muslim League, under the guidance of Mohammed Ali Jinnah, had already endorsed the idea of a separate nation for Indias Muslims. Nehru and Gandhi were using all means possible not to give in to that idea, to keep the country whole. The British were leaving anyway. How much did they really care? They were being accused of a history of divide-and-rule tactics that were culminating in Partition. Hindus and Muslims, encouraged by their own fanatics to be ever more mistrustful, were now pitted against one another. Riots were breaking out throughout the country, and Gandhi was rushing around trying to quell them with his policy of nonviolent resistance.

Until then, our school, Queen Marys Higher Secondary School, had been a haven of tolerance. Our class was fairly evenly divided between Hindus and Muslims. We picked our friends on the basis of intellectual companionship and common interests, not religion. My intimates included the Muslim twins Abida and Zahida; Sudha, a vegetarian Jain; and Promila, a Hindu Punjabi.

Abida and Zahida came to school wearing the most exquisite ghararas as their lower garments, with short kurtis (shirts) on top. Ghararas were worn only in Muslim families and resembled culottes. However, they were unlike the izarsthe wide, floor-length pajamasof my mothers childhood. Ghararas were so full of gathers that they gave the appearance of being floor-length, ample skirts. As all the gathers were pushed to the back and collected there, the general effect was that of an elegant bustle. Very smart, I thought. I wanted to wear them, too. I borrowed a gharara from Abida and had our tailor, Ram Narain, copy it several times over. Now all I needed were the long scarves, chunnis, the two-and-a-half-yard cloth pieces we draped across our bosoms and then threw back over our shouldersnot ordinary chunnis but the hand-dyed, hand-pleated ones, often with sparklers in them, that my Muslim friends wore.

I dragged my mother to the market to get a whole bolt of the finest mulmul (muslin). I cut this up into two-and-a-half-yard sections and left the pieces in a shop that specialized in covering them with the tiniest embroidered silver stars. Then I rushed them to the dyer and picked the shades I wantedaqua, a soft spring-leaf green, maroon, cobalt blue, peachand left clear instructions that the muslin needed to be heavily starched. Once this was done, I was left to do the hand-pleating myself. Each chunni took about two hours if I worked fast. The highly starched fabric wore down my fingers to the bone, but I was determined to do it. Abida and Zahida had taught me how.

It needed two people. My mother, or my younger sister, Veena, could always be drafted. The second person held a comfortable length of the chunni in front of her, as if she were playing the thread game Cats Cradle. I sat opposite them with my hands closed in loose-fist formation. I grabbed one edge of the fabric between my thumbs and curled fingers and proceeded to form the pleats, one at a time, in a kind of horizontal milking action, one hand moving quickly after the other, until I had gone across the whole width. I did this a million times for each chunni, then twisted the chunni like a rope several times over, so the pleats would firm up and hold. I could now float through school just like some of my friends, holding up the folds of my gharara elegantly to one side when I ran, my newly dyed, pleated, sparkling chunni dangling from my shoulders. I never did manage to look quite as elegant as Abida and Zahida, though. They had single, thick, ever-moving braids going down their backs all the way to the bottom of their hips. My two thinner braids, ending in ridiculous black-ribbon bows, ruined the entire effect.

Abida and Zahida excelled in mathematics and embroidery. I could barely even say the word mathematics without having clouds of confusion descend upon me. Mathematics and I were born on two separate planets. When given a choice in the upper school of higher or lower mathematics, I had quickly opted for the lower kind, which allowed me to drop algebra and geometry altogether. Lower mathematics, on the other hand, was a startling composite. It consisted of arithmetic, which I could just about manage, and domestic science, a catchall subject that must have drawn its inspiration directly from