CONTENTS

Climbing the Mango Trees

A Memoir of a Childhood in India

Madhur Jaffrey

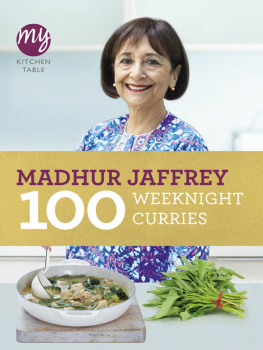

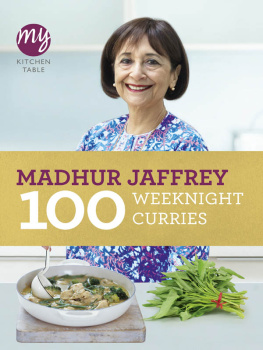

ALSO BY MADHUR JAFFREY

Madhur Jaffreys Ultimate Curry Bible

The definitive curry book by the world authority on Indian food.

Madhur Jaffreys Quick and Easy Indian Cookery

Over 75 delicious recipes that can be cooked in 30 minutes or less, demonstrating the versatility of authentic Indian cuisine.

Madhur Jaffreys Step-by-Step Cookery

Over 150 dishes from India and the Far East, including Thailand, Vietnam and Malaysia.

Madhur Jaffreys World Vegetarian

An unrivalled sourcebook of over 600 recipes and ingredients from all over the globe.

The Essential Madhur Jaffrey

A classic collection of Madhur Jaffreys best-loved recipes.

This book is dedicated to

Bari Bauwa and Babaji,

My Grandparents,

For

Helping make their grandchildren who we all are

And

To my daughters

Zia, Meera and Sakina

And their cousins,

As well as

To my grandchildren

Jamila, Cassius, and Rohan

For

Carrying on the line of the inkpot and quill set

So bravely

And so innocently

PROLOGUE

Goddess or Sweet as Honey? * Winter: The Season of Weddings The Caterer as Magician * Lessons in Taste

I WAS BORN in my grandparents sprawling house by the Yamuna River in Delhi. Grandmother welcomed me into this world by writing Om, which means I am in Sanskrit, on my tongue with a little finger dipped in honey.

Perhaps that moment was reinforced in my tiny head a month or so later when the family priest came to draw up my horoscope. He scribbled astrological symbols on a long scroll, and declared that my name should be Indrani or Goddess of the Heavens. My father, who never paid religious functionaries the slightest bit of attention, firmly named me Madhur, which means sweet as honey, an adjective from the Sanskrit noun madhu or honey. Apparently my grandfather teased my father, saying that he should have named me Manbhari or I am sated instead, as I was already the fifth child. But my father continued to procreate and I was left with honey on my palate and in my deepest soul.

My sweet tooth stayed firmly in control until the age of four when, emulating the passions of grown-ups, I began to explore the hot and the sour. My grandfather had built his house in what was once a thriving orchard of jujubes, mulberries, tamarinds and mangoes. His numerous grandchildren, like flocks of hungry birds, attacked the mangoes while they were still green and sour. As grown-ups snored through the hot afternoons in rooms cooled with wetted, sweet-smelling, vetiver curtains, the unsupervised children were on every branch of every mango tree armed with a ground mixture of salt, pepper, red chillies and roasted cumin. The older children on the higher branches peeled and sliced the mangoes with penknives and passed the slices down to the smaller fry on the lower branches. We dipped the slices into our spice mixture and ate; as our mouths tingled, we felt initiated into the world of grown-ups.

Winters were another matter. That was when the vegetable garden came into its own. Around eleven each morning, between breakfast and lunch, we would be served fresh tomato juice. At about the same time, the gardener would offer the ladies sunning themselves on the verandah a basket full of fresh peas, small kohlrabis, white radishes and feathery chickpea shoots. Some of these we ate raw and the rest were sent off to the kitchen after a studied appraisal (Radishes sweeter than last year, no?). As this was also the season when the men went hunting, the kitchen was deluged with mallards, geese, quail, partridge and venison as well.

Dinners were fairly generous affairs with about forty or more members of the extended family sitting down to venison kebabs laden with cardamom, tiny quail with hints of cinnamon, chickpea shoots stir-fried with green chillies and ginger, and small new potatoes browned with flecks of cumin and mango powder.

Winter was also the season of weddings. My father was in charge of the caterers and I was his permanent sidekick. In those days caterers had to cook at home and, certainly in our home, they had to cook under family supervision. So a gang of about a dozen caterers would arrive a few days before the wedding and set up their tent under the tamarind tree.

First, my father would examine all the raw ingredients. Were the spices wormy? Were there broken grains in the basmati rice? Were the cauliflower heads taut and young?

The outward suspicion from one side and obsequious reassurances from the other were a game each side dutifully played. In reality, we loved these caterers, who were known for the magic in their hands. They could conjure up the lamb meatballs of our erstwhile Moghul emperors and the tamarind chutneys of the street with equal ease. One of the few dishes that they alone cooked was cauliflower stems. For one meal they would cook the cauliflower heads. Then they were left with hundreds of coarse central stems. They cleverly slit them into quarters and stir-fried them in giant wok-like karhais with sprinklings of cumin, coriander, chillies, ginger and lots of sour mango powder. All we had to do was place a stem in our mouths, clamp down with our teeth and pull. Just as with artichoke leaves, all the spicy flesh would remain on our tongues as the coarse skin was drawn away and discarded.

Decades later, in New York City, I helped culinary guru James Beard my friend and neighbour teach some of his last classes when he was very ill. One of them was on taste. The students were made to taste nine different types of caviar and a variety of olive oils, and do a blind identification of meats with all their fat removed. Towards the end of the class, this big, frail man confined to a high directors chair asked, Do you think there is such a thing as taste memory?

This set me thinking. Once, several of us who had known each other for decades were sitting by a fireplace in France, talking and reading. My American husband, a violinist, was studying the score of Bachs Chaconne. Can you hear the music as you read it? a friend asked.

It was the same question in another form. When I left India to study in England, I could not cook at all but my palette had already recorded millions of flavours. From cumin to ginger, they were all in my head, waiting to be called to service. Rather like my husband, I could even hear the honey on my tongue.

CHAPTER ONE

Delhi Old and New * Sir Edwin Lutyens and the House that Never Was * Babaji * Number 7 The Lady in White * The Kite

THE ORCHARD SITE had housed our family homestead only since the early decades of the twentieth century. My family came from the walled city, often called Old Delhi, just to the south, built by the Moghul emperor Shah Jahan in the seventeenth century. My family referred to it simply as Shahar or the city.

There are many Delhis, as we were to study in school, built either alongside or wholly or partly on top of each other, often reusing materials from buildings knocked down in bloody efforts at domination. Our original family home was in Chailpuri, in the narrow lanes of the Old City. As its carefully chosen foundation, it had sturdy stones borrowed from the walls of Ferozshah Kotla, the fourteenth-century fortress and emperors palace.

Next page