About the Author

DAVID MARGOLICK is a contributing editor for Vanity Fair. Prior to that, he was the national legal affairs correspondent for the NewYork Times. He is a graduate of the University of Michigan and Stanford Law School. He has written two prior books: Undue Influence: The Epic Battle for the Johnson & Johnson Fortune and At the Bar: The Passions and Peccadillos of American Lawyers, a collection of his law columns for the NewYork Times. Strange Fruit originated as an article in Vanity Fair.

About the Foreword Contributor

HILTON ALS is a staff writer for The NewYorker. His first book, The Women, is out in paperback from Noonday Press.

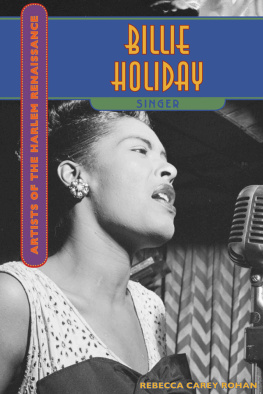

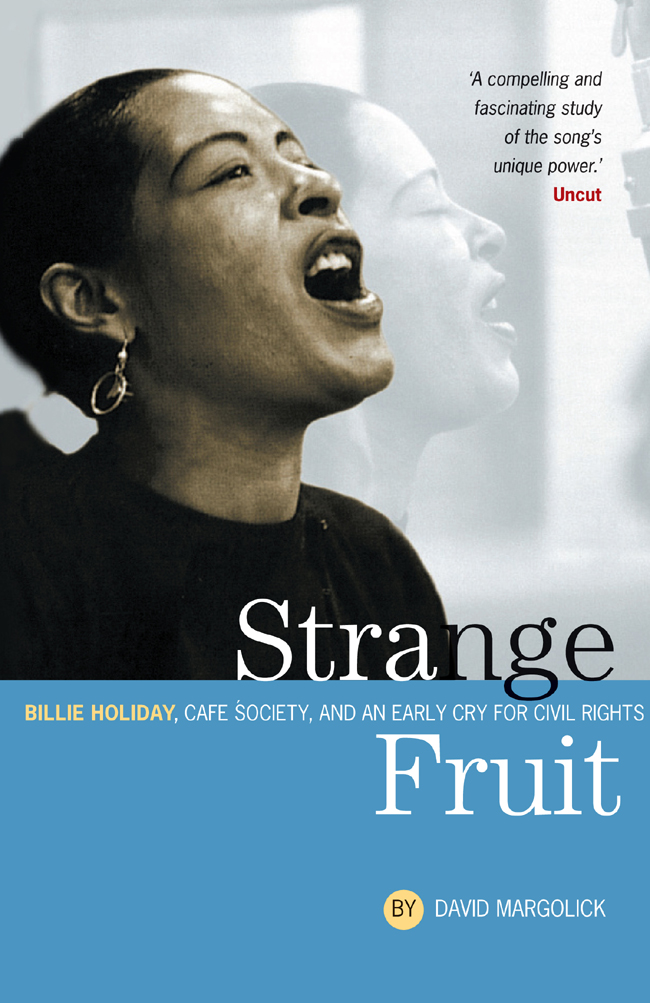

Strange Fruit

Billie Holiday, Caf Society,

and an Early Cry for Civil Ri

by David Margolick

Foreword by Hilton Als

CANONGATE

First published in 2000 by Running Press Book Publishers,

Philadelphia and London.

This digital edition first published in 2013 by Canongate Books

First published in Great Britain in 2001 by

Canongate Books Ltd, 14 High Street, Edinburgh, EH1 1TE

Text copyright 2000 by David Margolick.

The moral rights of the author have been asserted.

Strange Fruit by Lewis Allan

Copyright 1939 (Renewed) by Music Sales Corporation

All rights outside the US controlled by Edward B. Marks Music Company.

Used by permission. All rights reserved.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available upon

request from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 84195 284 2

ePub ISBN 978 1 78211 252 5

www.canongate.tv

Contents

To the City of New York,

which gave Strange Fruitand mea home

Acknowledgments

THIS BOOK was not only a labor of love, but labor-intensive, too. I have many debts to acknowledge.

First, there are the eyewitnesses: the people who experienced Strange Fruit firsthand, and shared their thoughts with me: Hey wood Hale Broun, Holmes Daddy-O Daylie, Ahmet Ertegun, Milt Gabler, Norman Granz, Lena Horne, Bernard and Honey Kassoy, Albert Murray, Max Roach, Ned Rorem, Pete Seeger, Artie Shaw, Studs Terkel, Bobby Tucker, Mal Waldron, and George Wein. There are those who've refreshed and perpetuated the song: Tori Amos, Dee Dee Bridgewater, Abbey Lincoln, Eartha Kitt, Cassandra Wilson.

Many other people assisted me. Apart from those quoted in the text, whose contributions are clearly apparent, these include Bob Adams, Michael Anderson, George Avakian, Charlie Bourgeois, Oscar Brand, Paul Buehl, Donald Clarke, Ron Cohen, Art D'Lugoff, William Dufty, Bill Ferris, Henry Foner, Leah Garchik, Marvin Gettleman, Farah Jasmine Griffin, John Jeremy, Ken Maley, Gertrude Margolick, David Ostwald, Carrie Rickey, Mark Satlov, Don Shirley, Chuck Stone, Elijah Wald, Jay Weston, Josh White, Jr., DouglasYeager, and Sidney Zion. My thanks to them all.

Two of the musicians I interviewedHarry Sweets Edison and Johnny Williamsdied before this book was completed, and I want to pay special tribute to them, as well as to the late Jack Millar, founder and guiding light of the Billie Holiday Circle, who was unfailingly courteous to me. The book was greatly enhanced by the help and encouragement of Abel Meeropol's two sons, Michael and Robert Meeropol. I also want to thank the many people who responded to my queries about Strange Fruit, recalling with great power and eloquence their associations with Billie Holiday, Josh White, and the song. It was a thrill to read their recollections and a privilege to include many of them in my book.

I want also to thank the incomparably knowledgeable and generous Dan Morgenstern at the Institute for Jazz Studies at Rutgers University;Tom Bourke and George Bozewick of the (also incomparable) New York Public Library; Sean Noel at Boston University; Peter Filardo at the Tamiment Library at New York University; Ralph Elder of the University of Texas; and Deborah Gillaspie of the Chicago Jazz Archive. The archive of my alma mater, the New York Times, is another inspiring institution, and I want to thank Lou Ferrer there for his cheerful assistance.

My editors at Vanity Fair, Graydon Carter and Doug Stumpf, were enthused about this project from the outset, and I am grateful to them. I am thankful, too, to Caroline Tiger, Carlo DeVito, Susan Oyama, Justin Loeber, Jennifer Worick, and the many other wonderful people at Running Press who encouraged me to revisit and expand upon my research, making it an even more rewarding experience for me.

DAVID MARGOLICK

NEWYORK, JANUARY 2000

Foreword

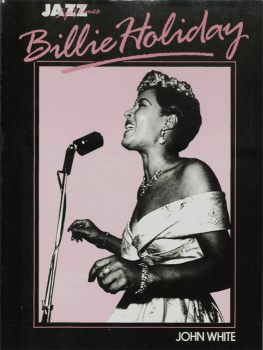

THERE APPEARS, in this valuable study about a significant moment in American popular music, American social life, and the distinctly American voice and presence of Miss Billie Holiday, an alarming bit of reporting. I'm trying to remember where this terrible thought first appears, so as to spare you the shock of it, but I don't want to look it up again; I found it painful enough to read the first time. I'm almost certain that it can be found twice in David Margolick's informative book, which is a large window into a small, albeit influential, world. What I'm referring to is a remark made by someone who knew Holiday. Margolick's source says something about Holiday's intelligence, pointing out that Billie Holiday, the star, did not read much in the way of real literature, did not have a large vocabulary, and had a fan's love of cheap romance stories about men and women who ended up on the sunny side of the street with no intimation of despair or death darkening their kisses, stories that espoused none of the terror or sarcasm or knowledge of slow death by injection with which Holiday herself infused even the happiest of her tunes, this potential candidate, we are given to understand, for Literacy Partners.

It's disgracefulthe very idea that Billie Holiday knew less than us because she reveled in what some would consider lowbrow entertainment, just as jazz was, in its time, considered lowbrow entertainment. That Holiday's preferred reading matter should be considered a reflection of her true selfhave we not had enough of Holiday as the crude romantic primitive, a prisoner of bad lyrics, too fat or too slovenly or just too stupid to clear all those teary technicolor Modern Romance tomes off her dressing table? It's cruel, and often racist or sexist or both, to measure this definer and re-shaper of American jazz and popular singing by the mediocre standards we set for ourselves. But there we are. The Western keepers of the canonour models of intelligencestill know so little about what makes up a Billie Holiday, let alone what makes her an authentic American female genius, a Titan in her output, that the question of her native intelligence is picked at like a scab by her detractors because she irritates them and their collective mind. Holiday makes no sense. She did not compromise her work. And she helped to create a world, a world where her voice would be at home, which is to say the world that David Margolick evokes in his seminal text about the end of NewYork's literal and figurative caf society.

Caf Society: The true home of the birth of cool, twenty years before Dizzy Gillespie and Charlie Parker donned their berets and wind instruments. It was a place that contributed greatly to the idea and reality of a New York that was, and is no longer: a citythe romantic viewthat did not demand so much compromise of its artists, a city that encouraged its inhabitants to search out the substance that could be found in the stylish affect of its artists, singing and playing, some of them, in the bars and clubs of Greenwich Village, home of Holiday's voice at Caf Society during a certain period in a city that is no longer.