Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this book are those of the author.

First published in 2017

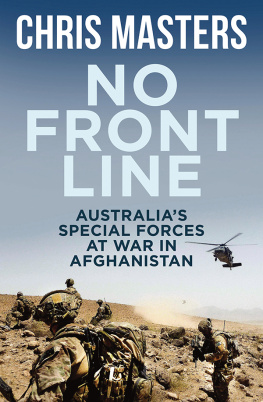

Copyright Chris Masters 2017

Map courtesy of the Australian Defence Force

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. The Australian Copyright Act 1968 (the Act) allows a maximum of one chapter or 10 per cent of this book, whichever is the greater, to be photocopied by any educational institution for its educational purposes provided that the educational institution (or body that administers it) has given a remuneration notice to the Copyright Agency (Australia) under the Act.

Allen & Unwin

83 Alexander Street

Crows Nest NSW 2065

Australia

Phone: (61 2) 8425 0100

Email:

Web: www.allenandunwin.com

Cataloguing-in-Publication details are available from the National Library of Australia

www.trove.nla.gov.au

ISBN 978 1 76011 114 4

eISBN 978 1 76063 896 2

Set by Midland Typesetters, Australia

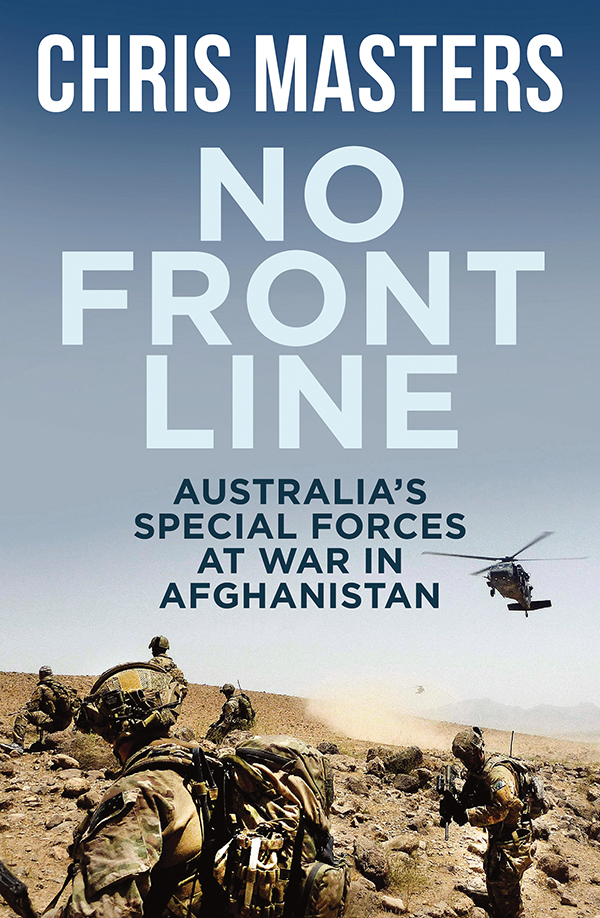

Cover design: Philip Campbell Design

Cover photo: Department of Defence

CONTENTS

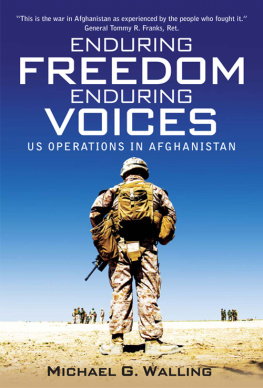

The Afghanistan story resists abbreviation. Propelled by curiosity to reach beyond a 140-characters version of Australias longest war, I have spent much of two decades asking questions. Why did the good war turn bad? Why, after all that investment in blood and treasure, could we not find a way to win? Is the place truly the graveyard of empires? While an answer contained to a sentence or two never emerged I did see a way to tell the story.

In Afghanistan, the devil is in the unavoidable detail. So why not get off the ramp with the soldiers at the very beginning and follow them all the way, threading through the maze of obstacles and challenges they encountered? To do so with an eye to restraining punishment of hindsightto better understand the evidentiary circumstance of the time and those split second moments that separate life and death.

Much of my personal motivation for what became another marathon can be traced to otherwise invisible moments deserving of honour. I wanted Australians to see what I saw out in those contested valleys. At Patrol Base Wali in the Mirabad Valley, a Dutch Provincial Reconstruction Team officer would step out every day and negotiate with farmers using as his principal weapons, reason and goodwill. It was impossibly difficult work. How do you improve lives while shielding locals from government corruption and Taliban retaliation? But that good global citizen persisted at considerable personal risk. His story was one of many to persuade me the humanitarian component of the coalition mission deserved emphasis.

I saw Australian soldiers also stepping out and again took stock of the quietness of their bravery. They were not so much looking for a fight as providing a protective presence. The risk was serious. Enemies might have been locals they were out to protect, or hardened itinerant insurgents who would hide and shoot. Along the footpads intersecting the fields were improvised explosive devices sown as if as thickly as the wheat, corn and poppy.

On 7 June 2010, the routine population centric patrolling began before dawn. Most of the soldiers I had been sharing a tent with left first. We went later and were back when a dull thud was heard and we looked across to see grey smoke billowing skyward. Snowy and Smithy, Sapper Jacob Moerland and Sapper Darren Smith, had been killed along with their dog Herbie. Their laughter and jostling before bedtime was fresh in my mind as I came to recognise I would go on to make plans for a thousand tomorrows, while never again would they wake to a new day.

I couldnt help but be affected. Nor could I hide my admiration for those young men and women, returning from a range of deployments confident that in general this generation has stood an age-old test of character.

You might not agree, but as far as I am concerned my personal empathy would not compromise professional objectivity. While I liked them I never wanted to be them. Rather, I wanted to tell their story.

But there was a limit, which investigative journalists find hard to abide. Hidden in plain sight at the main Tarin Kowt base was Camp Russell, the off-limits Special Forces compound. We could see them come and go, but we were not allowed access to their story. To a reporter, this always felt wrong. The Special Forces soldiers had the longest presence in country. At the spearhead of the fighting mission, their actions, as the most contentious, called at least for some scrutiny.

It took a while, but eventually I breached the Hesco at Camp Russell and became the first and only reporter to be embedded with Australian Special Forces. Up close it became clear they were not only special but different.

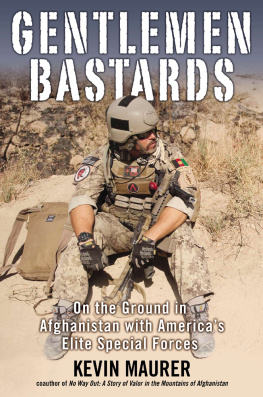

Australian Special Operations Command is comprised of around 2700 personnel with an annual budget of A$55 million. Operators are the Army, Navy and Air Forces brightest and best skilled. Over 180 courses are available and sixty training exercises ongoing.

Australias Special Air Service Regiment is the unabashed lead entity. After a gruelling winnowing process, it selects the best from all services. Although the hardest to know and read, I was able to inch close enough to recognise what all the fuss was about.

The Commandos, as a newer force element, were more accommodating, proud of the reputation they were forging and deserving of broader recognition. And here with all of them came a crunch. A core value of the Special Forces operator is the shunning of acclaim. So, you can imagine, put a reporter in the mix and there is intermittent confusion, with split personalities surfacing and cavorting like migrating whales. Sometimes they wanted to stay hidden and other times they wanted to show off.

The sappers, first badged as the Incident Response Regiment and later Special Operations Engineer Regiment, like their brothers out at Patrol Base Wali, were the most welcoming. Reputation for them was not so much a first order issue. They just got on with it.

Look across the Special Forces ranks and it is hard to find the ill formed, brash, post adolescent soldier boy. By their reckoning, at initial screening the Armys time-honoured dickhead filter rejects the unwise and immature. And by the time multiple courses, training exercises and reinforcement cycles are done, there is steadiness, measure and confidence in their bearing. But surfacing also is ego and exclusivity. It can get to a point where they identify more readily with the broader international Special Forces community than the uncommon soldiers of their own ilk.

Given the sensitivity of the subject matter, a deed of agreement was struck with the Australian Defence Force (ADF) that allowed for another screeningof this manuscript. There was no editorial censorship. The arrangement allowed for intervention only with regard to issues of operational security and protected identity.

The conduct of counter terrorism work in particular calls for anonymity. Operators and their families can and have been targeted. For this exercise, an identification protocol was developed that essentially removed surnames of serving operators. In other instances, the choice was given to them. Some were happy to be fully identified, others preferred the use of first name only and in a few instances only an initial is used.

For the most part, I was able to cover combat operations with minimal intervention. Some target names and technological capability factors were removed. One element of Special Forces operations in Afghanistan, its ultra-clandestine work, is not covered, partly because it would not have passed the censor, and partly because I know too little.