Researching a book which touches on many worlds, as Rezanovs story does, has been a humbling experience. It could not have been done without the help of dozens of people from St Petersburg to San Francisco who shared their expertise, scholarship, hospitality and friendship.

I would like to thank the following people in particular. In Sitka, the Tlingit woodcarver (and Blue Peter Badge-holder) Tommy Joseph keeps his peoples traditions alive and quietly boycotted the commemoration of the handover of Alaska from one group of white colonists to another as their party, not ours. Thad Poulson of the Sitka Sentinel was generous with contacts, while Dusty Kidd of the National Parks Service and Bob Medinger of the Sitka Historical Society were kind enough to organize a lunch of local historians in my honour. David Nordlander of the Library of Congress in Washington was invaluable in tracking down the Russian American Companys scattered archives and has been instrumental in putting much of the most important material online in the brilliant Meeting of Continents website.

In Juneau, I would like to thank bookshop owner and scholar Dee Longenbaugh for searching out hard-to-find monographs on Rezanov and for keeping in touch over several years with latest titbits which have come her way. Jim Simard at the Alaska State Archive and Steve Hendrickson at the Alaska State Museum helped me sift the often chaotic archives the Russians left behind them when they abandoned their American colony. Alan Engstrom the biographer of Alexander Baranov and discoverer of the true fate of Chirikovs crewmen in Jakobi Bay drove me around Juneau and introduced me to key Russian America scholars in both Alaska and Moscow.

In Kodiak, I explored the storm-lashed Artillery Point with Marnie Leist of the Alutiiq Museum. Father Ioann of the Holy Resurrection Cathedral in Kodiak keeps the Orthodox tradition alive in the church originally paid for by Alexander Baranov, and generously allowed me to examine the relics of Saint Hermann of Alaska kept in his church. Deacon Innocent (Phil Hayes) arranged for me to visit Spruce Island no easy feat, since communication was largely by text message picked up once every few days by the monks on the one remote point on the island with faint reception. The Fathers of St Michaels Skete (who modestly insisted that they not be named to avoid worldly vanity) rode five-foot high swells to transport me across the straits to their island home and graciously guided me around the habitations of St Hermann and his followers.

In San Francisco, Alla Sokoloff was kind enough to drive me to Benicia to pay our respects at Conchita Arguellos grave. Natalie Sabelnik of the Congress of Russian Americans introduced me to local historians and let me browse her archive a fascinating collection of flotsam washed up after the disappearance of the Russian empire and the scattering of many of its brightest and best to California, in Rezanovs footsteps.

At Fort Ross, Sarah Sweedler and Marion MacDonald were incredibly generous with their time and Hank Birnbaum keeps the Russian language alive at the Fort by marching platoons of musket-bearing schoolchildren around the compound to the command of Levo! Levo!

In Moscow, Vladimir Kolychev is the energetic head of the Russian American Society and indefatiguable organizer of events, from simultaneous bell-ringing in churches in Moscow and Kodiak to outings to productions of Junona I Avos . Kolychev is a great admirer of Rezanov and asked me not to be too hard on his memory: I hope he judges that I have been fair, at least. Dr Alexander Petrov has continued the late Professor Nikolai Bolkhovitinovs rigorous scholarship of Russian America. I greatly enjoyed open-air debates under the plane trees in a museum garden with Leonid Sverdlov, another of the greatest living experts on Rezanov.

In St Petersburg, Andrei Grinev has been kind enough to answer streams of questions on the finer points of Company history, and the Kunstkammers Sergei Korsun gave me an in-depth tour of the unique Tlingit articles collected by Lisiansky in 1804. In Kamchatka, Irina Vitter of the regional public library loaded me with advice and monographs, while I stayed at the home of Martha Madsen, a proud Kamchatkan by adoption.

I am particularly grateful to two scholars who took the time to read all or part of the manuscript and saved me from many embarrassing mistakes. Professor William McOmie of Kanagawa University in Yokohama worked through the Japanese sections several times over. Victoria Moessner, translator of Lwensterns diaries, spent many days correcting and commentating my account of Rezanovs voyages. My dear friends and colleagues Andrew Meier and Mark Franchetti both made invaluable suggestions on structure and style.

Michael Fishwick at Bloomsbury is the worlds finest editor not least because he knows what your book should really be about even if you dont. He is ably assisted by Anna Simpson and Oliver Holden-Rea. My agent Natasha Fairweather is an old and dear friend and mentor, who is also a fine deal-maker. If I am any historian at all it is thanks to my tutors at Christ Church, the late Patrick Wormald, William Thomas and Katya Andreyev.

Finally I would like to thank my wife Ksenia, who spent hours speed-reading tedious Russian archival sources as I took notes and who tolerated my long absences on the road in pursuit of my elusive hero.

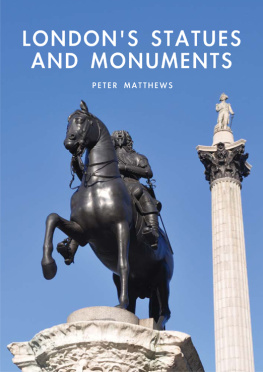

Owen Matthews read modern history at Oxford before becoming a journalist. He covered conflicts in Bosnia, Lebanon, Chechnya, Afghanistan and Iraq, and was Moscow Bureau Chief for Newsweek magazine.

His first book, Stalins Children , was published to critical acclaim in 2008, shortlisted for the Guardian First Book Award and the Orwell Prize for political writing, and selected as one of the Books of the Year by the Sunday Times , Sunday Telegraph and the Spectator . It has been translated into twenty-eight languages and the French version was shortlisted for the Prix Medicis 2009.

Owen Matthews lives in Istanbul and Moscow.

Stalins Children

1

Man and Nature

There, by the billows desolate,

He stood, with mighty thoughts elate,

And gazed...

Alexander Pushkin, The Bronze Horseman , 1833

Our Russian land can bring forth her own Platos,

And her own quick-witted Newtons...

Mikhail Lomonosov, The Delight of Earthly Kings and Kingdoms , 1741

No childhood could be more calculated to instil in a growing boy a sense of the supremacy of man over nature than growing up in St Petersburg as that great city rose from the marshes. In 1703 Peter the Great had ordered the construction of the first building on a sandy island on the northern bank of the Neva River, among mosquito-infested bogs criss-crossed by sluggish streams. A yearly levy of between thirty and forty thousand serfs one conscript for every nine households in the empire was brought on foot and under military escort to dig embankments and haul stone for the new palaces. Within two decades this slave army had transformed Peters plan into a great city of elegant houses and paved streets.

By the time Nikolai Petrovich Rezanov was born on 28 March 1763 in the modest Rezanov family house near the Admiralty, St Petersburg was already a European metropolis. The city could be called a wonder of the world, wrote the awestruck Hanoverian ambassador, was it only in consideration for the few years that have been employed in the raising of it. St Petersburg boasted an academy of sciences, a university, an academic gymnasium and a fine neoclassical cathedral, and its grid of streets had been laid out according to the latest principles of town planning by the finest architects of Europe.

The city was defined by its artificiality. Its genesis and continued existence were wholly dependent on the person of the Tsar. St Petersburg was the ultimate Residenzstadt a city built around an imperial court and financed by the state and, less willingly, the nobility. St Petersburg is just a court, a confused mass of palaces and hovels, of grands seigneurs surrounded by peasants and purveyors, wrote the French encyclopedist Denis Diderot in 1774 after visiting at the Empress Catherine the Greats invitation. interspersed with the wooden houses of the lesser nobility, forced by decree to maintain residences in the capital.

Next page