This book is dedicated to the bright and cherished memory of my parents, Cecil and Eileen Matthews, whose fortitude, humour and dedication carried us all through those manifestly difficult and troubled times.

To the immense courage of Franz Otto Laib, the German deputy commandant who saved my life, and to Helen Goldilocks Roschmann, the camp administrator and interpreter, whose devout values sustained many of the British prisoners in her charge; and to sister Annie, the German nurse who cared for all her patients, including my mother, in the camp hospital, irrespective of their race or creed.

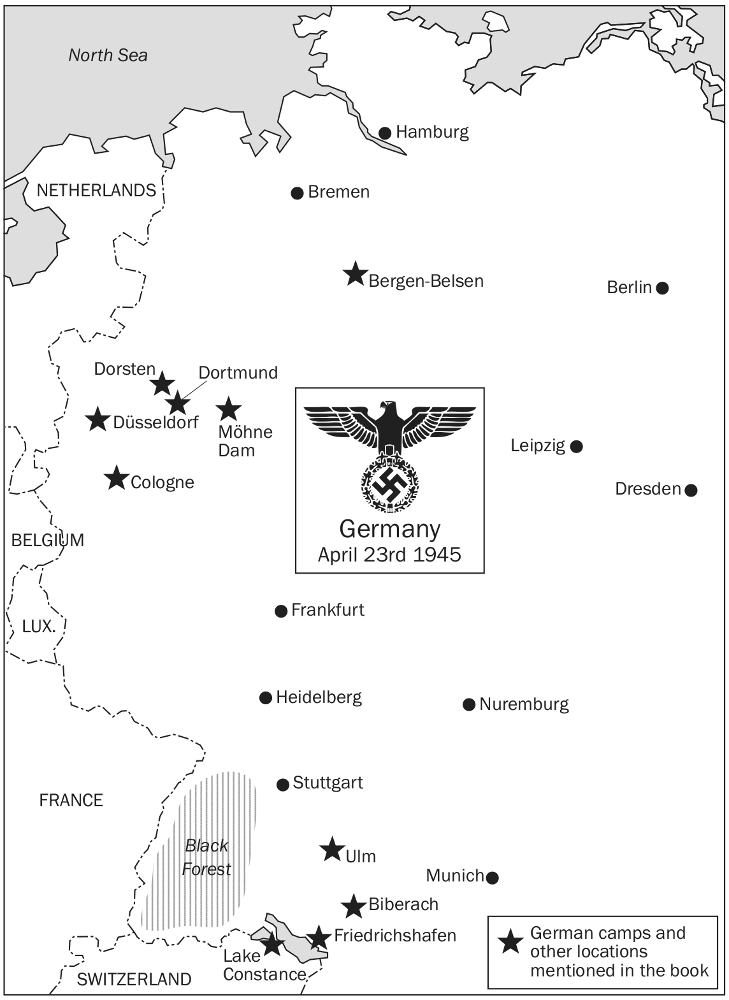

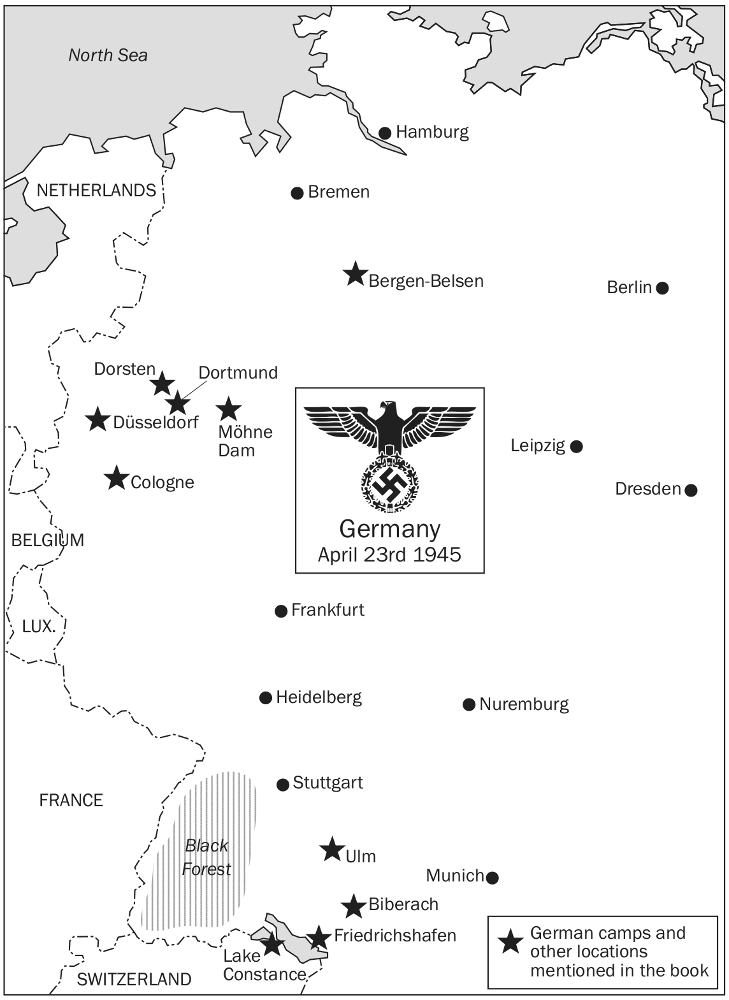

And, finally, to all those extraordinary Channel Islanders who touched my life, including my steadfast and lifelong friend Neville Henry Godwin, from our traumatic days in Dorsten and Biberach Concentration Camps.

Contents

Of all gifts that fortune grants us, there is none greater than friendship no greater wealth, no greater joy.

So in the spirit of this quotation from Epicurus of Samos, I am delighted to write a foreword for this book.

Here, close to the town of Biberach in southern Germany, the Lindele camp was located. When the French liberated the camp on 23 April 1945, they found internees from many nations. Though the camp was supervised by the International Red Cross, I do not want to euphemise the situation: the people interned here were robbed of their freedom.

Despite the close quarters, the lack of privacy, the cold and the continuous supervision, a spirit of humanity existed between the internees and the population of Biberach; for me, this is a very positive sign. Stephen Matthews reports about Franz Laib, the deputy camp commandant, who saved his life, entries in his mothers diary about Helen Roschmann, a translator at that time, and also contacts between women having their babies at the hospital, which led to friendships between people from Guernsey and Biberach, which have been fostered for generations. They sowed the seed for todays friendship between the island of Guernsey and the town of Biberach. Every year reciprocal visits take place, and former internees bring their families to Biberach. Both here and on the island there are people dedicated to perpetuating this friendship.

I would like to thank Stephen Matthews for his initiative in recalling so graphically this humane aspect of the Second World War and wish all the readers of this book the wealth and joy of friendship in the spirit of Epicuruss words.

Norbert Zeidler

Lord Mayor of Biberach

Most of the people who will read this book have lived through a time of peace in Western Europe and have not had to experience the World Wars during which our parents and grandparents suffered. Many of us will have heard first-hand accounts of World War Two from those who lived through it. Often, the stories will be of the bravery and courage of the men and (in some cases women) who fought for the freedoms we have enjoyed.

Those of us who have had the pleasure of living in the Channel Islands have heard from those civilians who suffered as the result of enemy occupation of their homes. I have heard many extraordinary and often heart-wrenching, as well as heart-warming, tales. Sadly, most of those who lived through the occupation never wrote down their experiences, often because the memories were too painful. Consequently, many stories are no longer remembered and will never be recalled.

Those, such as Stephen Matthews, who have recorded and preserved their memories have made a valuable and beneficial contribution to our understanding of all that war entails. We all need not only to remember the bravery of those who fought but also to realise the suffering endured by ordinary civilians. In doing so, we ensure that future generations will learn about the horrors and futility of war and will grow to realise that we must strive to maintain the peace and freedoms we currently enjoy.

We also learn that the hatred and evil encouraged and perpetrated by the leaders of nations are not always shared by their citizens. Compassion and humanity are not the characteristics solely of one side of the battle.

In this book Stephen Matthews conveys the memories of his own, and his familys, experiences of enemy occupation on the island of Guernsey, followed by deportation and internment in Germany. It is a personal tale not only of the horrors of war but also the love and compassion that human beings on both sides of the conflict were able to show to each other.

Such mutual respect for our fellow beings underpins the contacts that now exist between the communities of the Bailiwick of Guernsey and the town of Biberach. Through such friendships, understandings are able to grow between different communities; and, through those contacts and by remembering the suffering of our predecessors, we hope that we and our subsequent generations can continue to live in peace.

Sir Richard Collas

Bailiff of Guernsey

To the living we owe respect but to the

dead we owe only the truth.

Voltaire

T he stooped old man stood on the glistening cobbled stones of the Marktplatz, wrapped up in a warm overcoat and holding an umbrella close to him in a relentless battle against the driving rain and the bitter cold. He was here in the German town of Biberach an der Riss, to celebrate his liberation by Free French Forces from the nearby German concentration camp where he had been imprisoned with his parents some seventy years ago as a young boy. Standing there, he realised he was now one of only a few survivors literally a dying breed and, more poignantly, it was unlikely he would ever stand here again. He mused about the passing years: how did the intervening decades pass so quickly and when did hatred and anger on both sides become deep friendship and love, so that the raucous noise of war could be soothed by gentle music?

Was this how it felt to be an ageing dinosaur, at a time when a third of the population didnt know anything about the Battle of Britain and a quarter of them thought the Germans had been ontheAllied side in World War Two? Perhaps this was the right time to leave quietly. Pulling his coat snugly around him and tightening the woollen scarf around his neck in a vain attempt to stop the rain dripping down his neck, he smiled to himself as he was reminded that all his aches and pains were merely Gods way of telling him he was still alive, and with that he shuffled off into the gloom of the late afternoon.

So where did it all start? On reflection, it must have begun with my birth on 7 June 1938, when I finally made an appearance as the younger son of Cecil and Eileen Matthews. My parents resided happily in the upper-country parish of St Martin on the calm and feudal Channel Island of Guernsey, where my maternal forebears had lived and prospered for many hundreds of years. It has been said that our own personal traits and characteristics are formed between the ages of three and seven, and, by the time I reached my seventh birthday, I had been imprisoned, terrorised, threatened, starved, beaten, had my hand broken by a German guard, bombed, shelled, shot at, spat upon and finally stranded in a minefield.