This is largely an account of my youth, that is to say the thirty-some years it took me to claim my truth. (In a few places in the narrative Ive skipped forward briefly for the sake of completing a tale.) You may already have read some of these remembrancesin interviews and newspaper essays, or thinly disguised in one of my novelsso please know I reserve the right to plagiarize myself. I have reconstructed long-ago scenes and conversations to the best of my ability. Ive tried not to imagine anyones thoughts but my own.

WHEN I WAS A BOY IN Raleigh I was afraid of being locked in Oakwood Cemetery overnight. Every Sunday after church, when our blue-tailed white Pontiac cruised through the entrance, I fretted about the sign posted above us: GATES LOCKED AT 6 PM . I never voiced this fear to my parents, but it hovered over me like a threatening storm cloud all afternoon. What if we lose track of the time? That could easily happen as we plucked dandelions from my grandfathers grave or posed sullenly for Daddys never-ending slides, rigid as garden gnomes. Our family plot was on a rise with the other Nice Families, a respectable distance from the gate, so the caretaker, a runny-eyed old man who kept a spittoon in his granite cubbyhole, might overlook us when he left for home. That enormous gate would clang shut, and we would be trapped there all night, eating acorns for survival, drinking dew off the liliesmy brother, my sister, my parents, and meCemetery Family Robinson.

This was not your usual ghoulish graveyard terror, since I found the cemetery anything but spooky. I loved its winding lanes and tilting stones, the way its pale-green dells were flecked with pink in the spring. I reveled in its rich hieroglyphics, all those corroding angels and renegade jonquils, the palpable antiquity of the place. This was our family seat, after all, the ground to which I would return someday, permanently planted among my ancestors. So what was so scary about that? Folks in Raleigh might assume it had to do with the way my grandfather had died. But I wouldnt learn about that until later, when I was well into my teens and the matter of why we came to the cemetery every Sunday would finally be explained. Even then, though, my focus would remain on the writing on the stones, not on what actually lay in the boxes beneath them.

Oakwood Cemetery was not just the landscape of our past but also the very blueprint of our family for years to come. My father would eventually lay out the rules for his children in a self-published family history called Prologue, so named for a famous line in The Tempest: Whats past is prologue. Antonio uses the phrase to explain his intention to commit murder. My father used it to justify bragging about his ancestors, and he murdered the truth more than once in the process.

One thing is certain, the old man wrote after rattling off a roll call of all the lawyers, governors, planters, and generals in our family, is that wherever one of these men met success, there was a self-effacing and goodly lady by his side.

Back then I was still too young to realize that there would never be a lady by my side, goodly or otherwise. Nor would I have noticed how the old man had summarily reduced his wife and daughter to dutiful handmaidens. I felt only this shapeless longing, an oddly grown-up ennui born of alienation and silence. Some children experience this feeling very early on, long before we learn its name and finally let our headstrong hearts lead the way to True North. We grow up as another species entirely, lone gazelles lost amid the buffalo herd of our closest kin. Sooner or later, though, no matter where in the world we live, we must join the diaspora, venturing beyond our biological family to find our logical one, the one that actually makes sense for us. We have to, if we are to live without squandering our lives.

So maybe I was beginning to understand something on those Sunday afternoons in the cemetery. Maybe I sensed I didnt belong there, now or forever, that my true genealogy lay somewhere beyond these gates, with another tribe.

MY MOTHER HELPED ME WITH MY very first effort at writing. We were living in a duplex in Raleigh, on Forest Road, near the new shopping center. Out in California a three-year-old girl had fallen down an abandoned well, and I was determined to console her. I was only a few years older than this child, so my mother must have taken dictation. I couldnt begin to tell what I said. What could I have said?

Im sorry you fell down a well.

Please dont be sad.

I hope they get you out soon.

What I do remember is how Id pictured this letter being delivered: someone dropping it directly into the well, like a wishful coin consigned to a fountain, before it drifted down through the clammy darkness into the little girls outstretched hands. I figured she would be expecting the letter, awaiting my words of comfort. And my words, if I just chose them carefully enough, would save her in the end.

I suppose my mother must have heard a mailing address on the radio, one provided by the family. Either that or she never mailed the letter at all, intending it only as an exercise in empathy, a homemade remedy for her heartsick, overimaginative child.

The point is: I remember nothing, happy or sad, about the fate of Little Kathy Fiscus. A quick Googling reveals her name and the fact that her attempted rescue in 1949 was one of the first calamities ever to be broadcast live on television. I know now that the well was only eighteen inches wide and that the rescuers recovered Kathys body a hundred feet beneath the field where shed been playing three days earlier. The doctor who broke the news to thousands of rapt onlookers said she had died of suffocation only hours after the last time her voice was heard. A haunting detail, but one I dont remember. I would surely have remembered that voice.

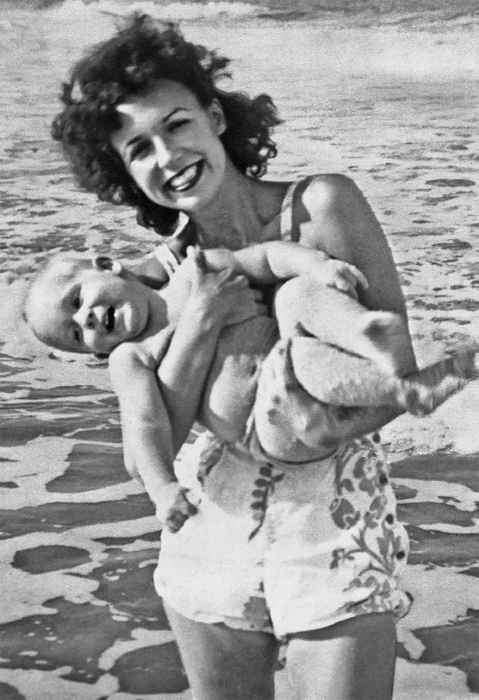

My mother must have changed the subject as soon as the truth was known, distracting me with a Little Golden Book or an antiques store. (I enjoyed antiquing at a revealingly early age.) My mother spent most of her life withholding things, shielding her children and her husband from uncomfortable truths. Im sure she must have learned this at the feet of her own mother, an English suffragette who had a few doozies of her own to hide. Still, my mother believed in the curative power of letters. She must have written thousands over the years. When she wasnt at The Bargain Box, selling used clothes for the Junior League, or hosting a radio panel show for teenagers, you could hear her writing in her den, clattering away on a millipede of a typewriter that popped out of a desk like a Victorian magic act.

I remember the letters she sent me at summer camp and how I reread them daily like a soldier at the front. There were four or five pages sometimes, covering the front and the back, the type inevitably crawling up the margins to a sideways ballpoint finale. Love,Mummie. That signature was my undoing at camp. Another boy spotted it, and since no kid in his right mind called his mother Mummie, there were immediate taunts about moldy pharaohs in their tombs, complete with bedsheet impersonations. My mother, who called her own mother Mummie, never knew of my humiliation. By the time I was a teenager I had decided to call her Mither, a name that struck me as elegant and ironic, so the joke could not possibly be on me. I did the same thing with my father who became Pap after years of being called Daddy, a name only children would use. I was learning to build my manly armor with words, being careful, so careful, like my mother.