THIS IS A BORZOI BOOK PUBLISHED BY ALFRED A. KNOPF

Copyright 2017 by John Mauceri

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York, and distributed in Canada by Random House of Canada, a division of Penguin Random House Canada Limited, Toronto.

www.aaknopf.com

Knopf, Borzoi Books, and the colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

Photographic credits: Beth Bergman, 1979, .

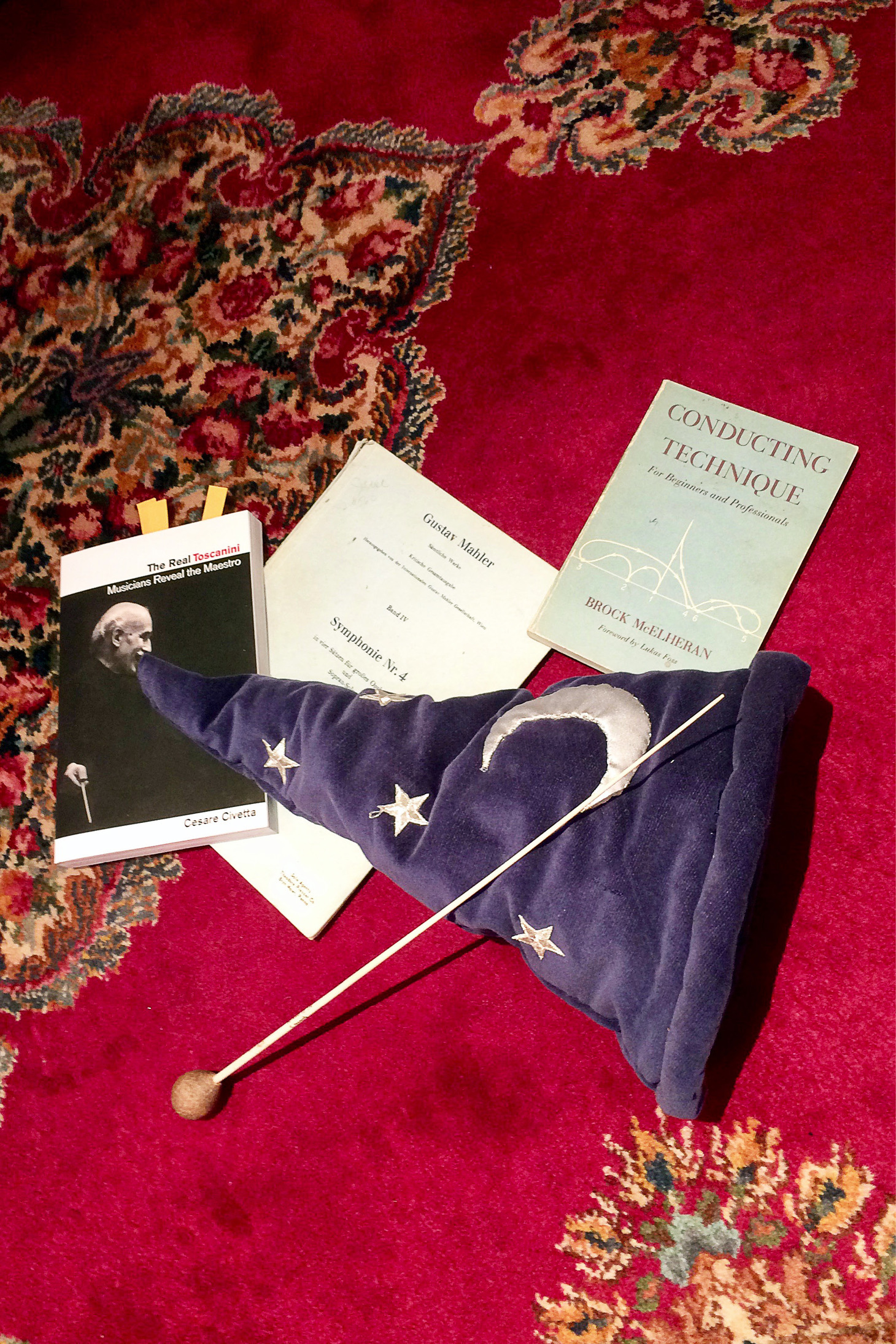

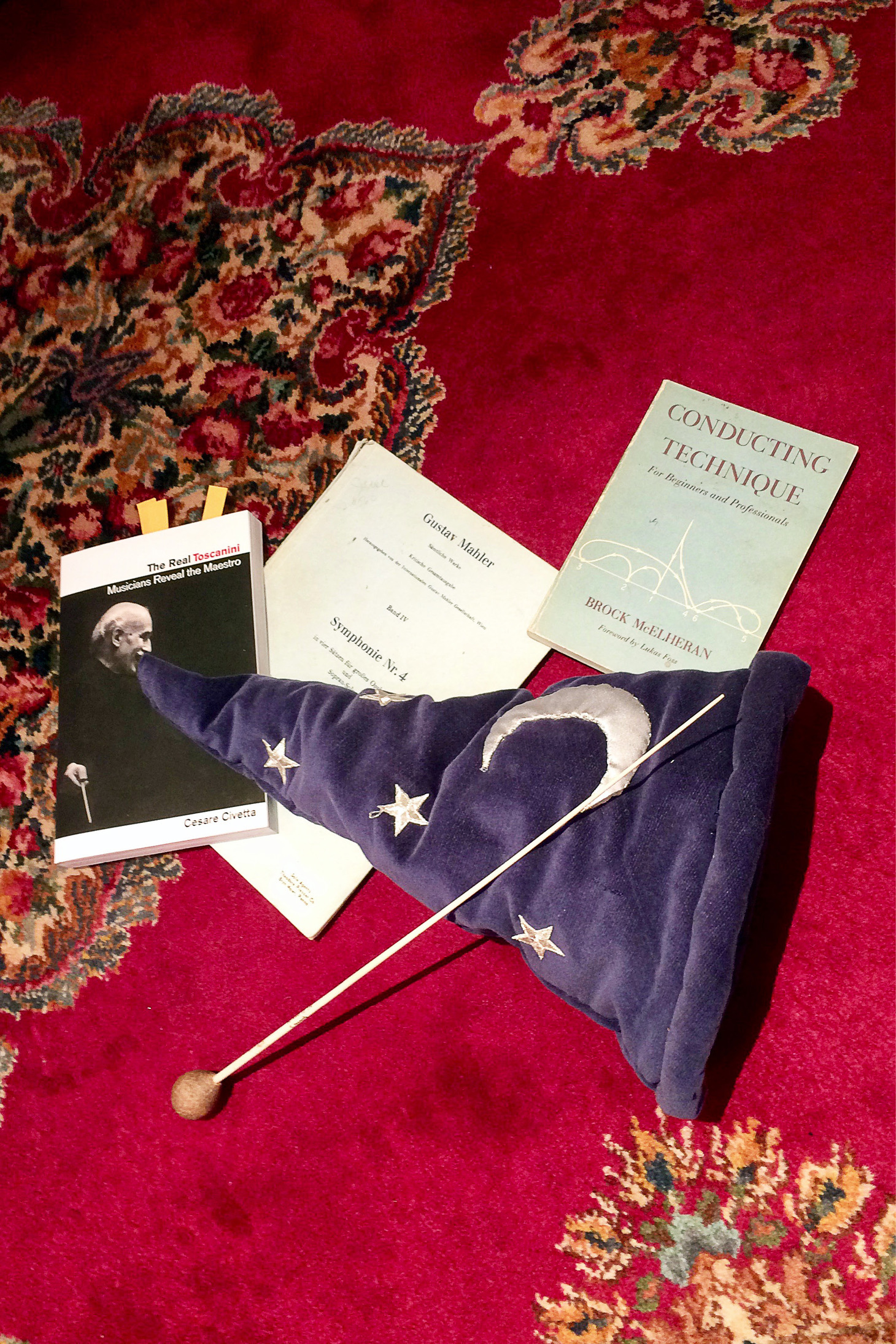

Grateful acknowledgment is made to Universal Edition (London) Ltd. for permission to reprint an excerpt from Mahler Symphony No. 4 edited by Erwin Ratz, copyright 1963 by Universal Edition (London) Ltd., London, copyright renewed. All rights reserved. Reprinted by permission of Universal Edition (London) Ltd.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Mauceri, John, author.

Title: Maestros and their music : the art and alchemy of conducting / by John Mauceri.

Description: First edition. | New York : Alfred A. Knopf, 2017. | Includes index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016055932 | ISBN 9780451494023 (hardcover)

ISBN 9780451494030 (eBook)

Subjects: LCSH: Conducting. | Conductors (Music)

Classification: LCC ML458 .M38 2017 | DDC 781.45dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016055932

Ebook ISBN9780451494030

Cover photograph by Rido/Shutterstock

Cover design by Stephanie Ross

v4.1

ep

Contents

To Gustav Meier

( 1929 2016 )

who took the time with me when I was nineteen years old. You were the first to teach me the craft and introduce me to the inexplicable.

Introduction

I f you were reading The New York Times on Thursday morning, January 7, 2016, you would have awoken to three obituaries of two conductors who could not have been more different from each other. Pierre Boulezprobably the most influential figure in classical music in the second half of the twentieth centuryreceived two obituaries and a photo on the front page, one by a former Times critic and devout apologist of modernism in music, Paul Griffiths, and another by the papers chief classical music critic, Anthony Tommasini. The third obituary, which included two photos, was for the millionaire and former publisher of a journal for pension-fund and financial managers, a man who could barely read music, by the name of Gilbert Kaplan, who shared something with Boulez: they both had conducted Mahlers epic Symphony no. 2 with the Vienna Philharmonic.

Boulez was a brilliant and precise musician. He was impeccably and rigorously trained in Paris and used his training and intelligence to significantly shape what classical music in the postWorld War II era became. His development as a conductor-composer was seen as visionary. When Leonard Bernstein stepped down as music director of the New York Philharmonic in 1969, Boulez was appointed his successor.

Kaplan, on the other hand, had studied law and worked on the New York Stock Exchange. After hearing a performance of Mahlers Symphony no. 2 conducted by Leopold Stokowski with the American Symphony Orchestra in 1965, he developed an obsession with the work. He sold his magazine, Institutional Investor, and became the chairman of the board of the American Symphony, to which he was the largest donor. He also bought the original manuscript of the Mahler symphony, along with one of Mahlers batons, and then paid various people to teach him how to conduct the piecewhat the German and Italian words in the score meant; how to move his arms; whom to look at and when. And in 1982 he hired the American Symphony, rehearsed it, and performed the work to an invited audience in Avery Fisher Hall (now David Geffen Hall) at Lincoln Center.

He conducted it from memory (which is more than Boulez ever did). His invited guests were thrilled with his achievement, but Kaplan was just getting started. He went on to conduct the symphony a hundred times and to record it with the London Symphony Orchestra and the Vienna Philharmonic. And if anyone thinks professional conductors think this is something to admire, you had better think again.

How is it possible for Boulez, the thoroughly trained musician who ruled the avant-garde and passed judgments on everyone and everything, dismissing all American composers with a single sentence (You have no composers, not even a HenzeHans Werner Henze being his German rival, who wrote music Boulez detested), to have intersected with a rank amateur? Boulez, the former antiestablishment enfant terrible, had come to represent the establishment practically overnight, with appointments in America at the New York Philharmonic and the Chicago Symphony, and in Paris with a contemporary-music institute that received the second-greatest national funding after the Louvre. Kaplan bought his orchestras and paid for his recordings. And yet not only did these two maestros have their performances of the same work with the samegreatestorchestras of the world compared, but in some cases Kaplans recordings were preferred.

And here, dear reader, is the great mystery of the conductor. Who are we? What are we doing? What defines greatness, not to mention competence? What if you, like numerous amateur critics (read the Internet), think Kaplans Mahler with the Vienna Philharmonic to be a revelation? What, then, of those who have spent their lives learning harmony, counterpoint, and score reading, entering competitions, painstakingly working their way up the ladder from assistant conductor in a regional orchestra to associate conductor to music director of a second-tier orchestra, and never have the opportunity to conduct Mahlers Second in Vienna?

In a very mysterious way, all of the above not only is possible, but makes a kind of nonsensical sense, because conducting is both bigger and smaller than you think. My purpose here is to explore its strange and lawless world, one in which everything and its opposite existeven as one tries to find the common denominators of greatness in our field, our art, our theater, and our job. When you love us, we are geniuses. When you dismiss us, we are charlatans. We are these things and moreand less, since we are simply human, even if we occasionally appear to be godlike to some. And just as in Greek mythology, there are stories of our conducting gods that help illuminate who we are and who we are not. Here is the first sentence of one:

On Saturday, August 30, 1975, Herbert von Karajan had lunch in his Salzburg residence with Leonard Bernstein.

The two greatest conductors of the second half of the twentieth century were archrivals, and while Bernstein was instrumental in lobbying to get Karajan to make his New York debutin spite of his past associations with the Nazi regimeKarajan was a major impediment to Bernsteins Austro-German career. And so any story that starts with the above sentence will inevitably get the attention of anyone interested in classical music. What was it like? What did they talk about? A nonpublicized meeting of the two competing and reigning