Contents

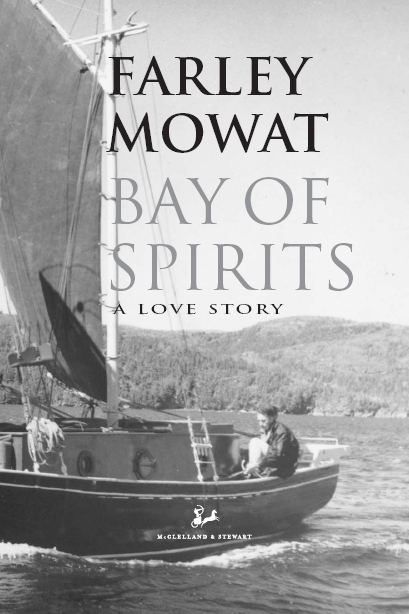

A love affair with a special woman and a special world.

I am deeply grateful to the many Newfoundlanders who bore with me, gave me access to their lives, and shared what they had with me and mine.

And the same to friend and publisher Susan Renouf, who has been and remains an unfailing source of encouragement and as accomplished and diligent an editor as any writer could hope to find.

Island in the Mist

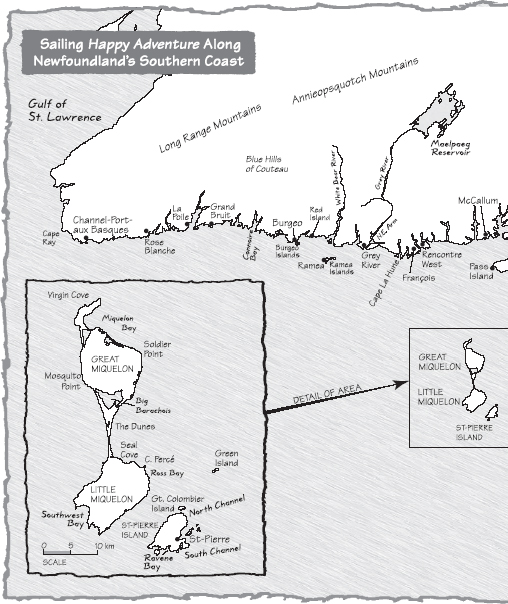

I n the summer of 1954 my father and I sailed his little ketch, Scotch Bonnet, down the St. Lawrence River to the sea. When a storm sent us scuttling into Rimouski on the lower river in search of shelter, we moored alongside an ocean-going rescue tug.

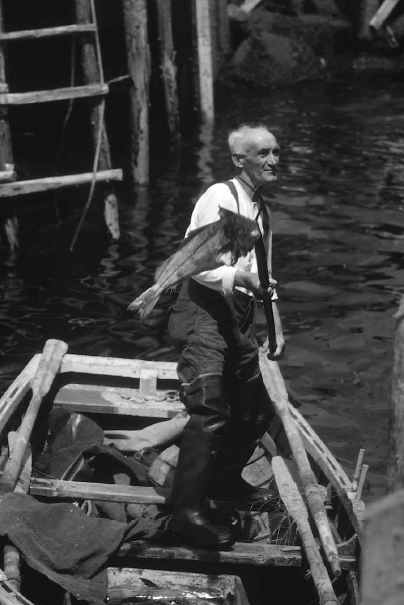

It was a safe mooring and a friendly one. The tugs crew consisted mostly of Newfoundlandersa breed of seamen I had not previously encountered. They invited us aboard their ship, plied us with rum, fed us bowls of a peculiar dish called fish-and-brewis, and, while the storm howled in the rigging aloft, told us stories of their seagoing life.

These tales so enthralled me that I was determined to know them better. When I asked the tugs skipper how best to go about meeting his kind on their home ground (or waters), he advised me to book passage on one of the little freight-and-passenger steamers serving Newfoundlands outport communities.

Shell give ye the feel of what our old Rocks like. Aye, and the sound of it, and the smell of it too. And if twas me Id carry a bottle or two aboard to ile the whistles of the folk you meets along the way.

Three years passed before I could take his advice. Then, in the late summer of 1957, I flew in to Sydney, Nova Scotia, and took a taxi to North Sydney, a compact little harbour that was home to a busy shipyard where coasting and fishing vessels were built and repaired. On the morning of my arrival a venerable three-masted schooner was cradled on the dry end of the marine railway up which she had been hauled, festooned with weeds, a few days earlier. She was being swarmed by twenty or thirty men armed with caulking irons, long-headed hammers, and great hanks of golden oakum made from teased-out strands of manila rope soaked in Stockholm tar. The caulkers were crawling all over her, busily driving bales of oakum into her gaping seams to keep her afloat for a few more years. The sound they made was like a confabulation of giant woodpeckers. It was a sound that had not changed much since Nelsons time. It rang down the centuries as I carried my gear up the gangplank of the ferry that would carry me across the Cabot Strait to that great island known to its people as the Rock.

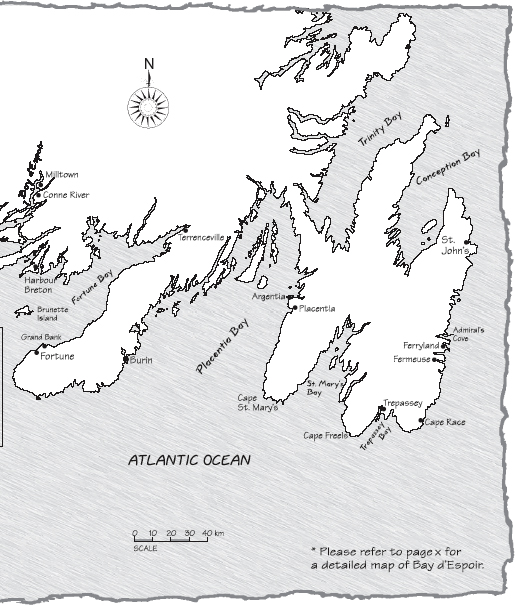

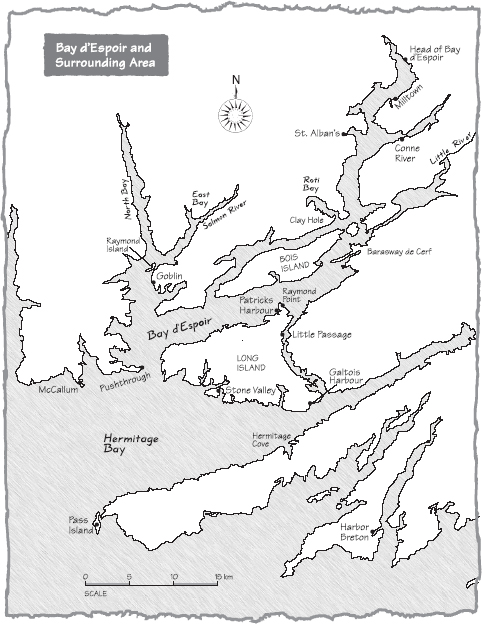

Newfoundland is of the sea. A mighty granite stopper thrust into the mouth of the Gulf of St. Lawrence, its coasts present more than five thousand miles of rocky headlands, bays, capes, and fiords to the sweep of the Atlantic. Everywhere hidden reefs, which are called, with dreadful explicitness, sunkers, wait to rip open the bellies of unwary vessels.

Fifty thousand years ago this great Rock was mastered by a tyranny of ice that stripped it of soil and vegetation and carried the detritus eastward to form the Grand Banks. The ice grinding relentlessly across the southern coast slashed a series of particularly deep fiords through the granite sea cliffs. Every few miles there was such an openingsometimes a narrow knife wound, sometimes wide enough to admit a dozen ships sailing abreast.

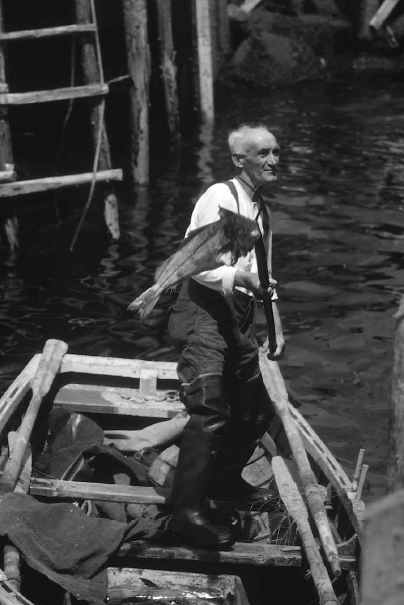

After the departure of the ice, the high plateau of the interior was able to support only the most tenacious life. It was a world notably inhospitable to people of European origin. The first such interlopers to reach southern Newfoundland, perhaps as early as six centuries ago, were, however, men of the sea, not of the land. They were fishers in pursuit of cod for food, of walrus for ivory, of whales for oil, with little or no interest in the interior. They found the brooding granite barrier of the south coast adequate for their needs. It contained countless nooks and crannies well suited to shelter their boats, fishing stages, and houses, so there they planted themselves, always within sailing or rowing distance of the enormously rich coastal fishing grounds.

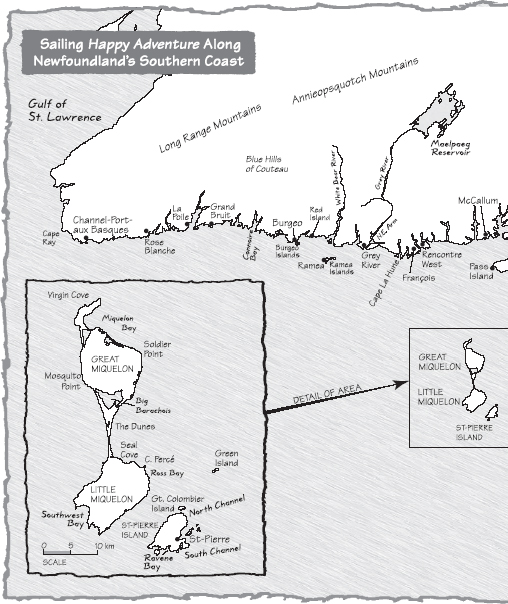

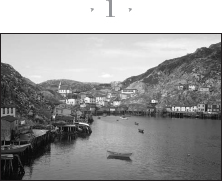

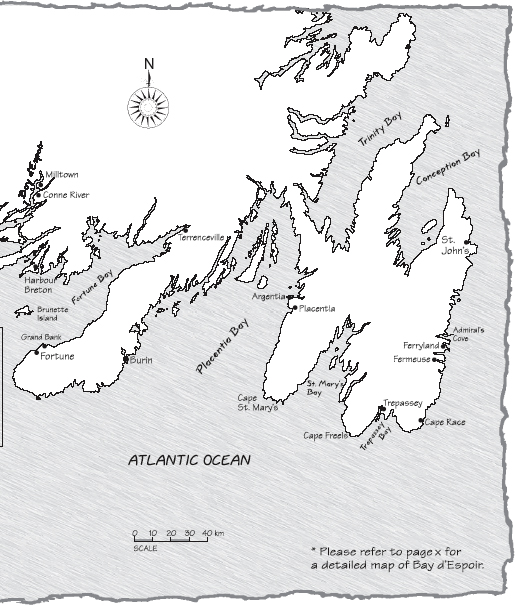

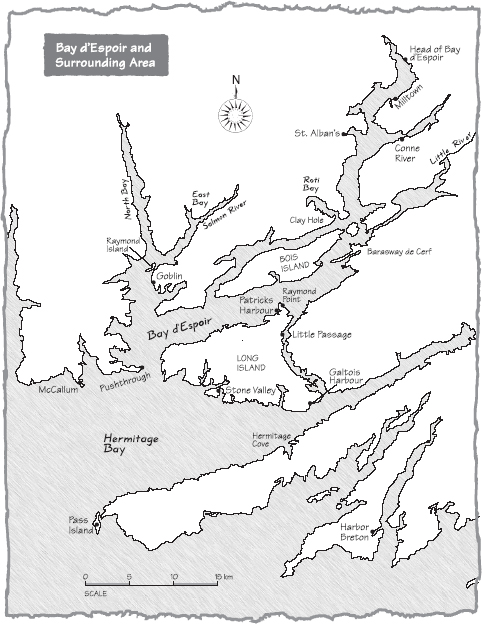

When Newfoundland joined Canada in 1949, more than eighty such outports dotted the Souwest Coast, the name bestowed on the wall of cliffs and fiords stretching from Port aux Basques in Newfoundlands southwestern corner to the bottom end of Fortune Bay, more than two hundred miles to the eastward. Although some had as few as a dozen inhabitants, others held a hundred or more. Each was a little world of its own, living by and on the sea. First used as summer fishing stations by itinerant Basque, Portuguese, French, and English fishermen, they gradually acquired permanent residents by attracting runaways, castaways, and fugitives from the law and from the poverty of their European homelands. The names of these little lodgings of humanity, with their hodgepodge of linguistic origins much corrupted through the centuries, suggest their origins. Some that were still extant when I first visited the Souwest Coast included Fox Roost (Fosse Rouge), Isle aux Morts, Rose Blanche (Roche Blanc), Harbour le Cou, Gallyboy, Grand Bruit, Ramea, Burgeo, La Hune, Cul de Sac, Rencontre, Dragon, Mosquito, Pushthrough, Goblin, Lobscouse Cove, Mose Ambrose, Belleoram, Femme, and Fortune.

By 1957 only thirty-eight of the original eighty still existed. The rest had fallen victim to the post-Confederation craze for centralization. Pressure brought to bear by the Newfoundland and federal governments had already resulted in the death of more than half of the islands outport communities whose inhabitants had been encouraged, bribed, or threatened into abandoning their age-old homes and ways of life in order to move to larger centres, mostly in the interior, where they were supposed to become productive citizens of the modern industrialized world.

A fleet of small passenger and freighter steamers operated by the maritime branch of Canadian National Railways continued to provide a lifeline for the remaining outporters on the Souwest Coast, which was without either roads or airports. The coastal steamers numbered half a dozen, including the

![Farley Mowat - People of the Deer [Paperback]](/uploads/posts/book/52958/thumbs/farley-mowat-people-of-the-deer-paperback.jpg)