J OHN M UIR

John Muir was born on April 21, 1838, in Dunbar, Scotland, the third of eight children of Daniel Muir and Anne Gilrye Muir. In 1849, the Muir family immigrated to the United States and settled on a farm near Portage, Wisconsin. As the eldest son, Muir labored unremittingly on the family farm, where his affection for the wilderness and his interest in science and literature took root. In 1860, Muirs inventiveness in the design of machines led to an exhibit at the state fair in Madison; the acclaim his inventions received resulted in numerous job offers and Muirs acceptance at the University of Wisconsin.

Although Muir never received a degree (he left after three years), he studied geology and botany, discovered Emerson and Thoreau, and began to develop a conception of the natural world independent of his fathers stricter religious one. Still, it would be several years before Muir would make the study and preservation of the wilderness his lifes work.

In September 1867, his sight restored after a serious eye injury, Muir set out on what was to become a 1,000-mile walk from Indiana to Florida. He then traveled to California, arriving in San Francisco in March 1868, and walked for six weeks across the state until he arrived at the Sierra Nevada mountains, where he would spend much of the next ten years exploring the place he called the Range of Light.

Journals from these excursions would be collected in book form in My First Summer in the Sierra (1911) and A Thousand-Mile Walk to the Gulf (1916). But Muirs earliest published writings appeared as magazine articles on Sierra geology and the glacial origin of the Yosemite Valley. He would go on to publish nearly one hundred essays and articles in newspapers and magazines such as the San Francisco Bulletin, Overland Monthly, and Scribners Monthly. Admirers of Muirs work like Ralph Waldo Emerson and President Theodore Roosevelt were known to have met Muir and to have been touched by his passion for the wilderness.

In 1879, Muir made his first of many trips to Alaska, where he discovered Glacier Bay. The following year, Muir married Louise Strentzel, the daughter of a wealthy fruit rancher, and moved to Martinez, California. Muir spent much of his time managing the Strentzel ranch and raising his daughters, Wanda and Helen. In 1888, Muirs wife sold parcels of the family estate to allow Muir more time for his Sierra studies.

Soon after, Muir met Robert Underwood Johnson, associate editor of The Century Magazine, who encouraged him to write two articles on the need to protect the wilderness of the Yosemite Valley. These articles appeared in The Century in the fall of 1890. Wilderness preservation, thanks to Muirs literary zeal and Johnsons lobbying efforts, received more publicity than ever before; their efforts paid off and Yosemite was designated a national park. In 1892, Muir, Johnson, and others founded the Sierra Club, and Muir served as its president until his death in 1914.

Another fruitful result of Muirs friendship with Johnson was the publication of Muirs first book, The Mountains of California. Published in 1894, The Mountains of California was an instant success and continued Muirs education of his countrymen in the advantages of wild country. Muir would continue to write on behalf of the wilderness, and he published, among other books, Our National Parks (1901), The Yosemite (1912), The Story of My Boyhoodand Youth (1913), and Travels in Alaska (1915). Though Muir was crucial to the designation of Sequoia, Mount Rainier, the Petrified Forest, and the Grand Canyon as national parks, he lost his last preservationist battle over the damming of the Hetch Hetchy Valley in Yosemite. Nonetheless, he would set a national environmental movement in motion that continues today.

John Muir died of pneumonia in January 1914 while visiting one of his daughters in California. Muirs legacy is vast and includes Muir Glacier in Alaska, and in California the John Muir Trail, the John Muir Historic Site in Martinez, and Muir Woods National Monument.

C ONTENTS

TRAVELS IN ALASKA

PART I.

PART II.

PART III.

I LLUSTRATIONS

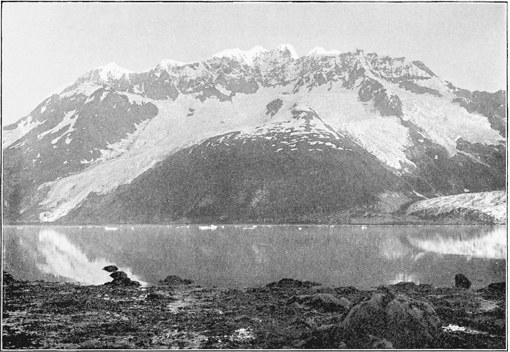

The Muir Glacier in the Seventies, Showing Ice Cliffs and Stranded Icebergs

From a photograph owned by Mr. Muir

Ruins of Buried Forest, East Side of Muir Glacier

From a photograph owned by Mr. Muir

Except as otherwise indicated the illustrations are from photographs by Herbert W. Gleason.

I NTRODUCTION

Edward Hoagland

John Muir (18381914), being diligent first and a dreamer second, wore many hats. So although he was a visionarya founder of the Sierra Club and savior of Yosemite National Parkwe do have quite a wonderfully meticulous record of the progress of his visions. In middle age and on the brink of his belated marriage, after considerable wandering in the Great Lakes and Appalachian wildernesses as a rattled and anguished but indefatigable young man, and then more definitively in Californias High Sierra as an amateur botanist and geologist, he went almost inevitably to Alaska. Where else would an American rhapsodist of wild places ultimately go? Joy, in fact, was his currency, though he didnt know it at the time. He thought that in such scenic mightiness he was studying glaciers: and he did do some original work on them. But a century and a quarter later, we are reading his account because there in the glorious fiords, the great fresh unblighted, unredeemed wilderness, he is at our elbow, nudging us along, prompting us to understand that heaven is on earthis the Earthand rapture is the sensible response wherever a clear line of sight remains.

Thoreaus more famous agenda, back East in Massachusetts sixty years before Travels in Alaska was finished, had been to try to alter the way that people lived, both with regard to nature and each other. Thus, wilderness figured as rather a minor factor in Waldens ruminations. The godhead could be located much nearer home, in a backlot pond (earths eye), as well as in a mountain massif. At one point elsewhere Thoreau advocated that every township should preserve one square mile in a natural state. Hardly a wilderness but sufficientyou didnt need to roam the frontier in order to find it.

Muir, although he carried a volume of Thoreaus essays on his first trip to Alaska, seems to have expected that you did, and we are the beneficiaries because he exerted his string-bean frame so strenuously to search. The journal jottings from which he fashioned most of his books, often decades later, were originally the product of scientific more than literary ambition, but otherwise were hymns of praise. He lived for Emersonian Transcendentalism perhaps more single-mindedly than even Emerson or Thoreauwho were involved in the Abolition movement and other controversies, such as womens rights and the injustice of the Mexican War, and the contemporary intellectual currents that they lectured on for a livelihoodan activity that the shyer Muir didnt begin to take to until later in life, and then only as a polemicist for the cause of preservation.