John Muir

and

the Ice That Started a Fire

Also by Kim Heacox

Memoir:

The Only Kayak

Biography:

Shackletons Challenge

Essays & Photography:

Alaska Light

Alaskas Inside Passage

In Denali

Iditarod Spirit

Natural History & Conservation:

Visions of a Wild America

Antarctica: The Last Continent

History & Conservation:

An American Idea: The Making of the National Parks

Fiction:

Caribou Crossing

John Muir

and

the Ice That Started a Fire

How a Visionary and the Glaciers of Alaska Changed America

Kim Heacox

Copyright 2014 by Kim Heacox

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, except as may be expressly permitted in writing from the publisher. Requests for permission should be addressed to Globe Pequot Press, Attn: Rights and Permissions Department, PO Box 480, Guilford, CT 06437.

Lyons Press is an imprint of Globe Pequot Press.

Project editor: Meredith Dias

Layout: Melissa Evarts

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Heacox, Kim.

John Muir and the ice that started a fire : how a visionary and the

glaciers of Alaska changed America / Kim Heacox.

pages cm

ISBN 978-1-4930-0867-4 (ePub)

1. Nature conservationAlaska. 2. GlaciersAlaska. 3. Muir, John,

1838-1914. 4. Climatic changesAlaska. I. Title.

QH76.5.A4H43 2014

333.7209798dc23

2013050235

for William E. (Bill) Brown,

Historian (ret.), US National Park Service

The Master Builder chose for a tool not the earthquake nor lightning to rend and split asunder, not the stormy torrent nor eroding rain, but the tender snowflowers, noiselessly falling through unnumbered seasons.

JOHN MUIR

I learned from Muir the gentle art of sleeping on a rock,

curled like a squirrel around a boulder.

S. HALL YOUNG

AUTHORS NOTE

For the sake of simplicity and to avoid confusion, John Muir is referred to in this book as a naturalist and a casual glaciologist, while during his time (and still today) he would more accurately have been regarded by friendly scientists as a glacial geologist, one who studies the impacts of glaciers on the landscape, as opposed to a glaciologist, who studies the physics and chemistry of glacial ice, its composition, and dynamics. As for the word Tlingit, John Muir and S. Hall Young used different spellings. This book quotes them as they spelled the word in various forms.

Steeped in western thought, Muir and Young often wrote about Tlingit chiefs, whereas Tlingit hierarchy was more complex, honorary, and highly evolved. Today most Tlingits prefer the titles house master, clan leader, and headman. The term Hoonah refers to the Tlingit village on the north shore of Chichagof Island; the term Huna refers to the Tlingit people who lived there. Muir and Young used different spellings here as well.

I refer to John Muirs father, Daniel, as a Calvinist, a member of the Church of England, as he was raised. While he remained faithful to Calvinisms basic tenets, in adulthood a disillusioned Daniel Muir joined the Secessionist Church and later the Campbellites, also known as the Disciples of Christ, before taking his family to America as a preaching elder. Because the term Calvinist broadly frames the core of his upbringing and lifelong values, and is more commonly known and understood, I chose it over Campbellite. Last, I refer to S. Hall Young as Reverend Young (as opposed to Minister Young, etc.), as thats how John Muir addressed him in their correspondence.

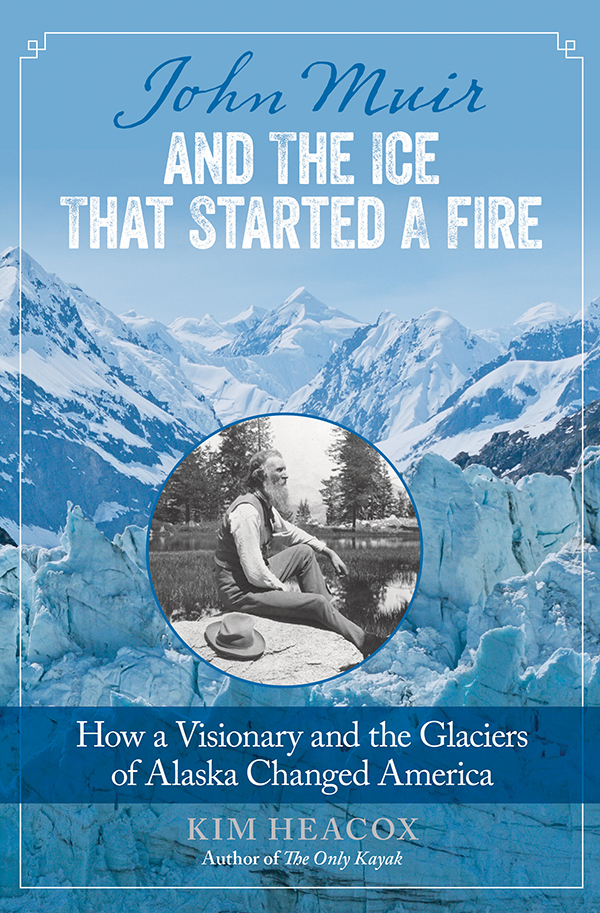

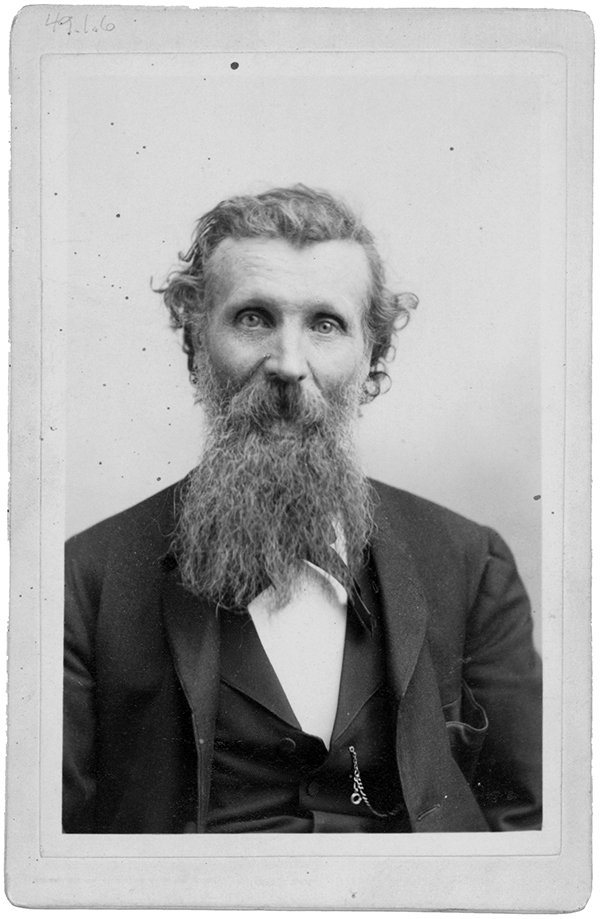

John Muir at about the time he first went to Alaska

Photo courtesy of Holt-Atherton Special Collections, University of the Pacific

Contents

PROLOGUE

the gospel of glaciers

WAS IT MADNESS?

A death wish of some kind?

The five Tlingit Indians said little as they glanced at the quiet missionary sitting among them and stabbed the sea with each stroke, paddling their cedar canoe northwest into iceberg-filled waters where no man dared to go this time of year. No man, unless he was a seal hunter. No man, until this other man came along, their second passenger, the one up front who scribbled notes and nibbled on dry crusts of bread. No hunter at all. More of an observer, charismatic in his own way, a good listener, a real talker, this scrappy, bearded Muir, his blue-gray eyes drinking up the country. Half wise elder, half wondrous child, he seemed interested in everything.

Shouldnt somebody say something? Insist on turning around? They could all die, be overturned and drowned by Kushtaka, the trickster land otter man of Tlingit legend. Or, if they continued on, they might receive mercy from Gunakadeit, a benevolent sea monster.

Onward, Muir compelled them. Onward to the glaciers, he would say. Never mind the wind or rain or ice or cold.

A DOUR SKY pressed down. Rain occasionally lashed them. Pieces of floating ice, calved from tidewater glaciers up ahead, tapped an ancient, forgotten language against the canoe. Ice everywhere, and little sign of life in a land that was once rich in salmon, berries, forests, and firewood. Most of that is gone now, the lands richness and bounty having been destroyed by an advancing glacier that evicted the Tlingits and entombed the bay for many generations, in some places swallowing entire mountains. Only recently had the glacier begun a dramatic retreat, unveiling a vast, raw, woodless, ice-chafed land in somber shades of gray. A foreboding place.

Summer was over. It was yeis, autumn time, the month Americans called October. Soon it would snow, and the cold, carved moon would turn brittle in the tangle of winter stars. The glaciers would grow still under deep blankets of snow, and darkness would strike all moisture from the air; stillness would pound the land silent, and stretch all the way to the Arctic.

John Muir was forty-one that autumn, engaged to be married the next spring to the only daughter of a prosperous California fruit merchant. With her reluctant blessingdo not be vexed with me, she wrote himhe had come to Alaska to see glaciers firsthand, to find out how they worked and shaped the land, how they carved rock and moved mountains. All to help buttress his theory that glaciers, not catastrophic down-faulting, had shaped his beloved Yosemite Valley and much of the Sierra Nevada, the mountains Muir called the Range of Light.

While Muir often rode in the front of the canoe, the other white man, S. Hall Young, a Presbyterian missionary, rode farther back. If anybody were to argue for turning around and getting them out of there, it would not be Young. In Muirs company he was a follower. Young had met the effervescent California naturalist more than three months before, in early July, in Fort Wrangell, some two hundred miles by water to the south; he saw in Muir a man to be admired, not questioned. It would be up to Toyatte, the Tlingit chief and captain of the thirty-five-foot canoe, to bring this adventure to an end. But Toyatte might have seen in Muir the same thing Young saw.