About the Author

Laurie Wilson is an art historian and practising psychoanalyst on the faculty of the Psychoanalytic Institute at NYU Medical School. Her involvement with Nevelson dates back to the 1970s when she spent fifteen hours interviewing the artist for her doctoral dissertation, Louise Nevelson Iconography and Sources (1976), which was subsequently published in the series Outstanding Dissertations in the Fine Arts. She has also written over a dozen chapters, articles and essays on Nevelson for professional journals and publications, including essays for the 1980 Whitney Museum exhibit, for which she conducted additional interviews with the artist.

CONTENTS

My work is the mirror of my consciousness.

Louise Nevelson, 1974. Barbaralee Diamonstein, Louise Nevelson at 75 Ive Never Yet Stopped Digging Daily for What Life Is All About, Art News (October 1974)

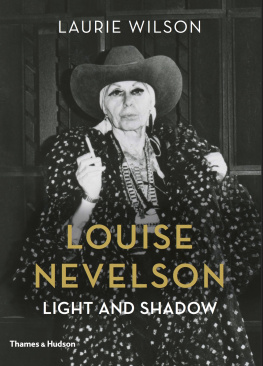

Who is the woman on the cover of this book? A Russian princess? A gypsy queen? No. She is Louise Nevelson, or Mrs. N, as she was known in her downtown neighborhood in New York City. (And her royal residence, Mrs. Ns Palace, is at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.)

During her long life, which stretched from 1899 to 1988, Nevelson was considered to be one of the greatest women artists of the twentieth century and, along with David Smith, Isamu Noguchi, and Alexander Calder, one of the four greatest American sculptors. For twenty-five years, from the time she began to exhibit her work, critics praised her art but she sold almost nothing. Then in 1958, at age fifty-nine, she hit the big time. And during the next twenty-eight years of non-stop work she churned out thousands of sculptures, collages, drawings, and prints, and she became a star. She changed the way we look at things wrote Hilton Kramer, chief art critic of The New York Times. No matter the fame she earned and the attention she attracted, she was always happiest in her studio. Her indefatigable energy was poured into her work.

I met with Louise Nevelson a number of times in 1976 and 1977, as she was the subject of my doctoral dissertation in art history from the City University of New York. I knew a fair bit about the New York scene, so I thought I was well equipped to write about Nevelson, who had gone to the same art school I hadthe Art Students League. At our first meeting in 1976, Nevelson told me that my task would be to show the world thatafter Picassoshe was the most important artist of the twentieth century. She loved to talk about herself and was remarkably open with me. I concluded that she was grandiose and self-centereda classic narcissist. We met again in 1979, when I was writing five catalogue essays for her forthcoming exhibition at the Whitney Museum, Atmosphere and Environments.

I continued to be fascinated by her work, especially by the trajectory she had traversed before arriving at her signature style in the late 1950swalls of black boxes, creating both an atmosphere and an environment. She had become the ground-breaking and unique artist whose sculpted environments started a tsunami that is still ongoing. But now it is called installation art.

By the time I met her in 1976, she had also become famous, the doyenne of American artists. Lightbulbs flashed when she walked into a room. Reporters gathered around her, ready to report her every move, pithy remark, or controversial opinion (on everything from the joys of freelance sex to the perils of motherhood and marriage). She was often at the White House. That year, at the age of seventy-six, she had a New York City park named for her, and she filled it with seven large steel and aluminum sculptures. On the occasion of her eightieth birthday, New York City gave her a huge party. She looked far younger than her chronological age, and her astounding energy made it possible for her to produce forty to fifty sculptures a yearsome of them large-scale steel works.

She was the only woman artist in America to make it entirely on her own. She separated from Charles Nevelson in the early 1930s, so no rich husband. No supportive lover, eitherthe men in her life were younger, drank more heavily, and were no match for her professionally or personally. While she was friendly with the most famous members of the New York SchoolMark Rothko and Willem de Kooningshe faced significant challenges in order to be taken as seriously as them. Some women artists, especially those who failed where she succeeded, hated her. But she had learned in early childhood that she would have to fend for herself if she wanted anything of life.

To be sure, Nevelson was not completely alone. All artists need intermediaries to promote their art and to make it possible to develop a career. Since the middle of the nineteenth century, galleries or art dealers have been the most common intermediaries between artist and public. Louise Nevelson had four major dealersKarl Nierendorf, Colette Roberts, Martha Jackson, and, most famously, Arnold Arne Glimcher. Each played a crucial role. They helped her achieve international status as one of Americas most important woman artists.

The version of herself that Nevelson created and presented to the world often had her saying, I am not bright. But anyone foolish enough to believe that soon discovered that Louise Nevelson was highly intelligent. Her pseudo-dimness was a defense against being seen as undereducated or inarticulate.

Louise Nevelson was unique, a one-off. She had her own style of dressing, of living, and of sculpting. Her work looked like no one elses. She never looked the way artists were supposed to look; even when she was broke, she managed to look like a million dollars. In the 1930s and 40s she became known as The Hat because she wore gorgeous chapeauxsometimes stolen and sometimes purchased by lovers for her favors.

Despite her later reputation as a fashionista, Nevelson almost always selected clothes for multiple purposes. When she was poor, she took a rare bit of extra money and spent it on a wool dressby an expensive British designerat Bergdorf Goodmans. It was a long-sleeved, full-skirted black jersey, perfect for Englands damp, cold weather (as well as an unheated loft on New Yorks Lower East Side). She bought it for its warmth as well as its beauty, and she wore it all winter to elegant parties and slept in it at night.

What kind of a person was Louise Nevelson? How did her wit and warmth get conveyed in her work, when to some she had an aloof, even regal presence? In public she was most comfortable with a proud, straight-backed stance, though among close friends she could be wonderfully witty, warm, and down-to earth. She said that she couldnt bend, that she was like a cigar-store Indian, made of wood. But she had many admirers and friendsDorothy Miller of MoMA, Edward Albee, Merce Cunningham, and John Cage loved her.

Long before the womens movement got underway, Nevelson was living the life she wanted, sleeping with the men she was attracted to, swearing like a sailor to prove her populist credentials, and never taking a day jobsince that would keep her from the thing she cared most about. Making her art was the only thing that really mattered to her. At one point I thought about titling this book Vissi dArte, the aria Tosca sings to the world telling it in glorious melodic tones that, above all else I lived for art.

As Nevelson herself said: I needed something to engage me, and art was that something. It was my entire life.

Next page