CONTENTS

Dedication

This book is dedicated to my family Shirley, Harry and Josh.

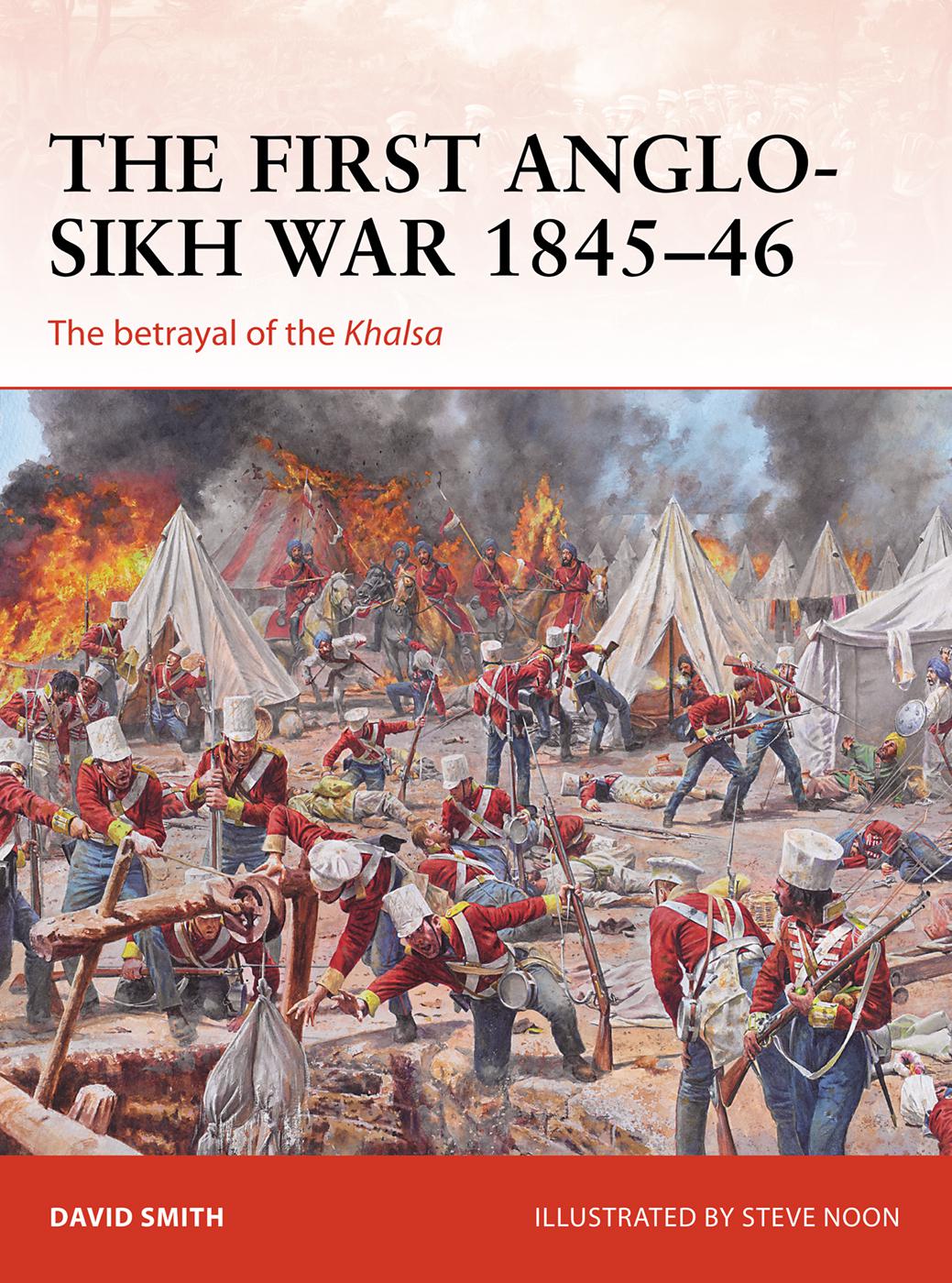

ORIGINS OF THE CAMPAIGN

The First Anglo-Sikh War is quite possibly unique, inasmuch as both sides entered into hostilities with exactly the same aim. Both the ruling aristocracy of the Sikh state and the British, in the form of the East India Company, entered the war with the primary goal of destroying the Sikh Army. The British saw it as a serious threat to their growing dominance over India, while the rulers of the Sikh state saw it as a threat to their very existence.

The great Sikh Maharajah Ranjit Singh is said to have gazed upon a map of India, noting the areas shaded red to denote their control by the East India Company, and to have commented, one day it will all be red. If this is more than mere legend, then this could be seen as the first step towards war with the British. The historian Amarpal Singh has termed the conflict an inevitable trial of strength between the two powers, but it only became inevitable after Ranjit Singhs death. Prior to that, he was both the driving force in the expansion of the Sikh Army, and the only person capable of controlling it.

The collapse of the Mughal Empire, by the end of the previous century, had left a number of kings and princes in control of various regions. The East India Company, exploiting political divisions and disunity among the Indian states, as well as the superior discipline of its own army, began to assume control over large swathes of the country until Kashmir, the Punjab and Sind were left as the main independent regions. In the Punjab, states known as misls were successful in expelling their Afghan controllers, but although they could work together against a common foe, they also continually squabbled among each other for control of resources and territory and were unable to coalesce into a unified state. The emergence of Ranjit Singh changed this situation, as he had the personality and political ability to unite the Sikhs under his rule. After declaring himself maharajah in 1801, he set about pulling the disunited misls together.

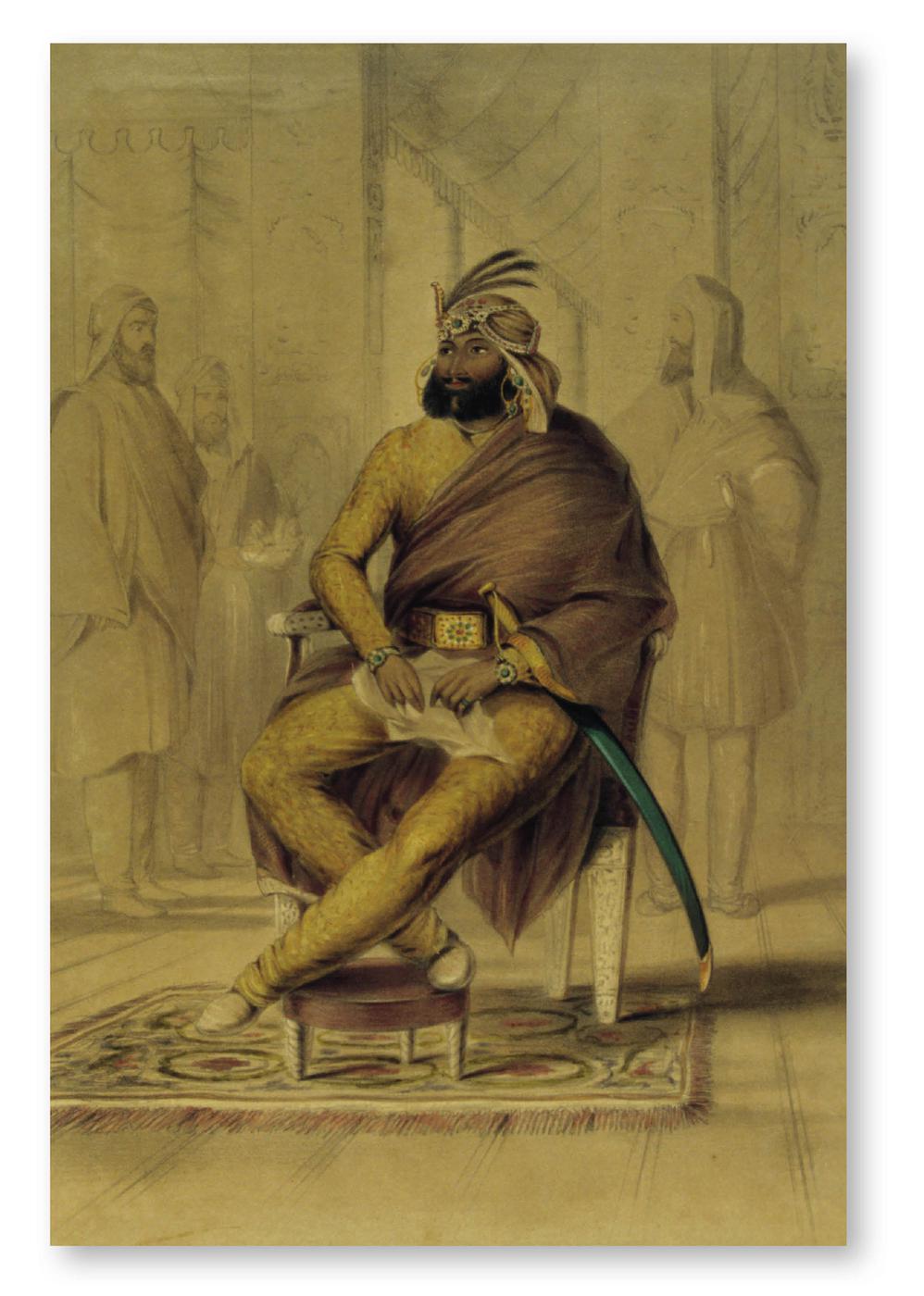

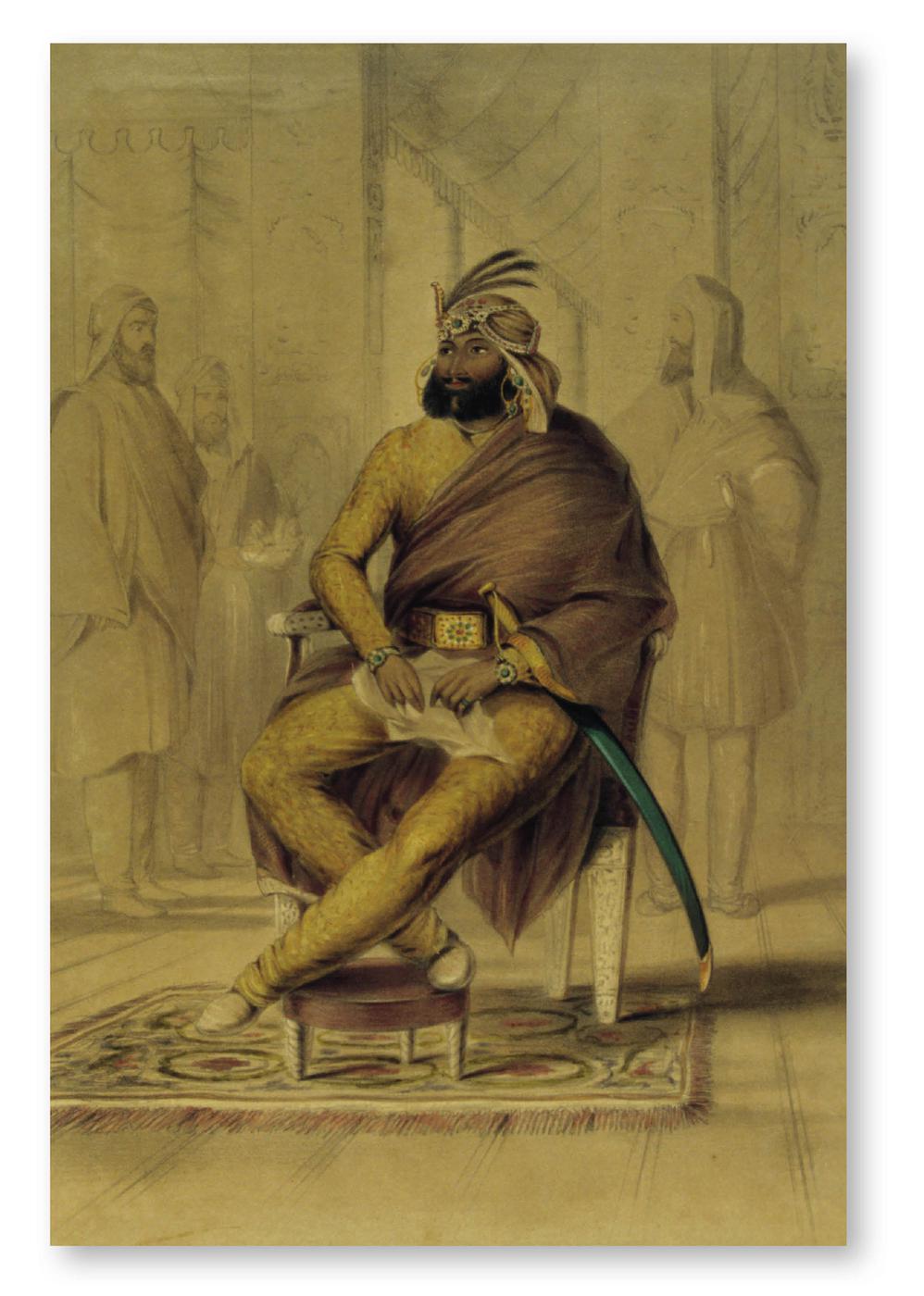

Ranjit Singh, the driving force behind the solidification and expansion of the Sikh state, foresaw trouble with the army of the East India Company and developed his army accordingly. (IndiaPictures/UIG via Get ty Images)

Trouble may well have erupted earlier, as Ranjit Singh had ambitions to expand his empire south of the Sutlej River, but the Treaty of Amritsar of 1809 (which recognized British control of this region) calmed the situation. Indeed, the British were happy to have a settled, unified Sikh state to act as a buffer between their own dominions and the troublesome regions to the north. The period of good relations between the Sikhs and the British also allowed Ranjit Singh to continue with his consolidation of the Sikh state, but the East India Company was still viewed as a potential future rival. Ranjit Singh therefore embarked upon a series of reforms to his army, specifically designed to counter British forces.

Sikh military tradition placed cavalry at the heart of the army, but Ranjit Singh had noted how disciplined infantry repeatedly won the day for the British. He therefore tipped the traditional hierarchy on its head and made the infantry the elite of his army. A powerful artillery force backed up these foot soldiers, with the cavalry reduced to a secondary role. European drill was introduced, and foreign officers were welcomed to instil discipline.

By the time Ranjit Singh died, on 27 June 1839, the Sikh Army was a formidable force and a clear challenger to the East India Company should anyone wish to point it in that direction. An infantry contingent of 47,000 was supplemented by 16,000 cavalry and almost 500 guns of various calibres. An army on such a scale placed a huge strain on the empires finances and only continued expansion of the Sikh state could support this. The limit on Sikh expansion imposed by the British was therefore an important element in the unrest that was to come. More important, however, was the death of Ranjit Singh, which plunged the state into chaos. Shorn of their powerful leader, rival factions fell into bickering over the succession and a series of ineffectual rulers took turns to deepen the crisis. In fact, exactly the sort of political infighting that the British had been able to exploit in other regions of the country now fragmented the Sikh state, making it simultaneously a more vulnerable target for the British to consider and a cause for concern.

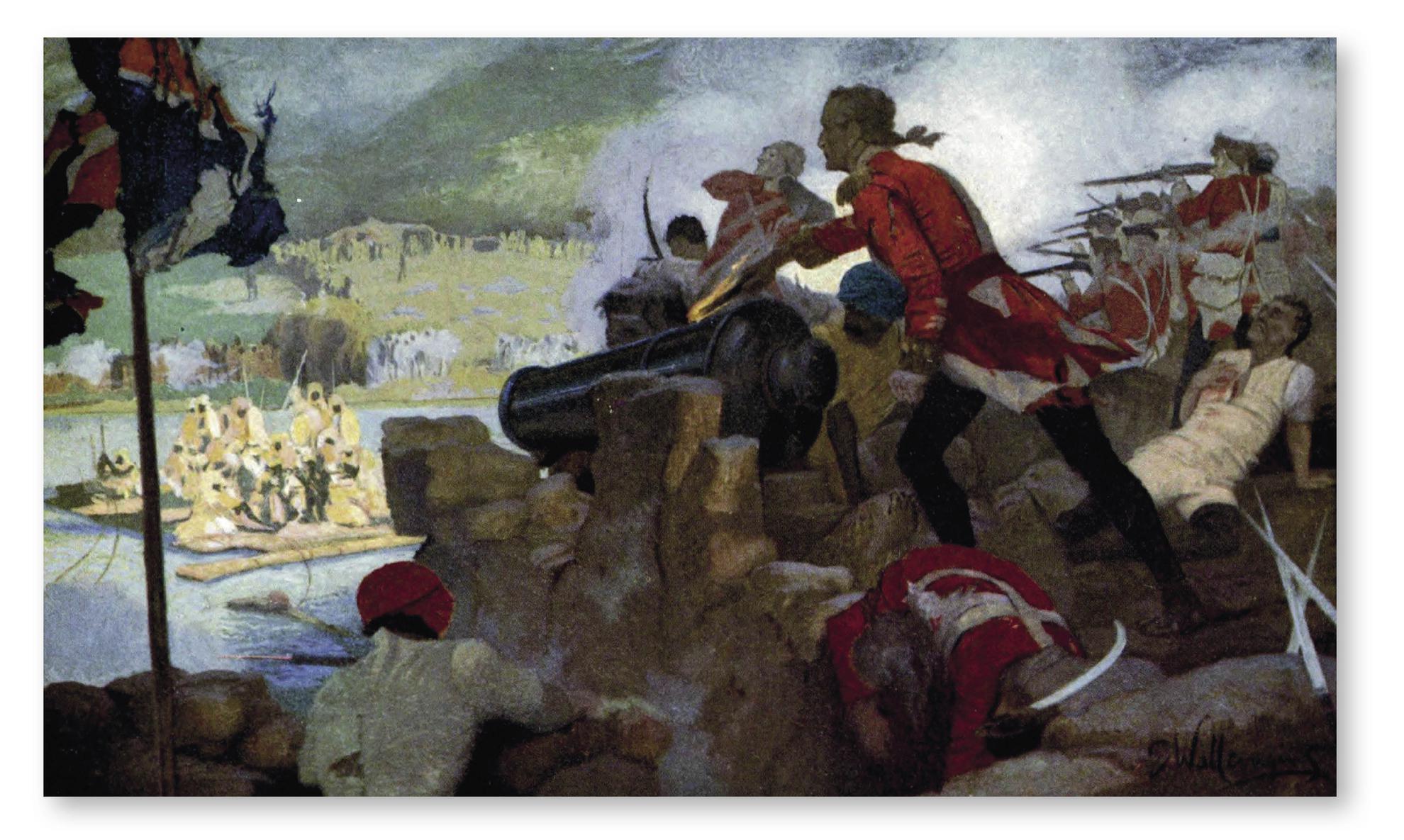

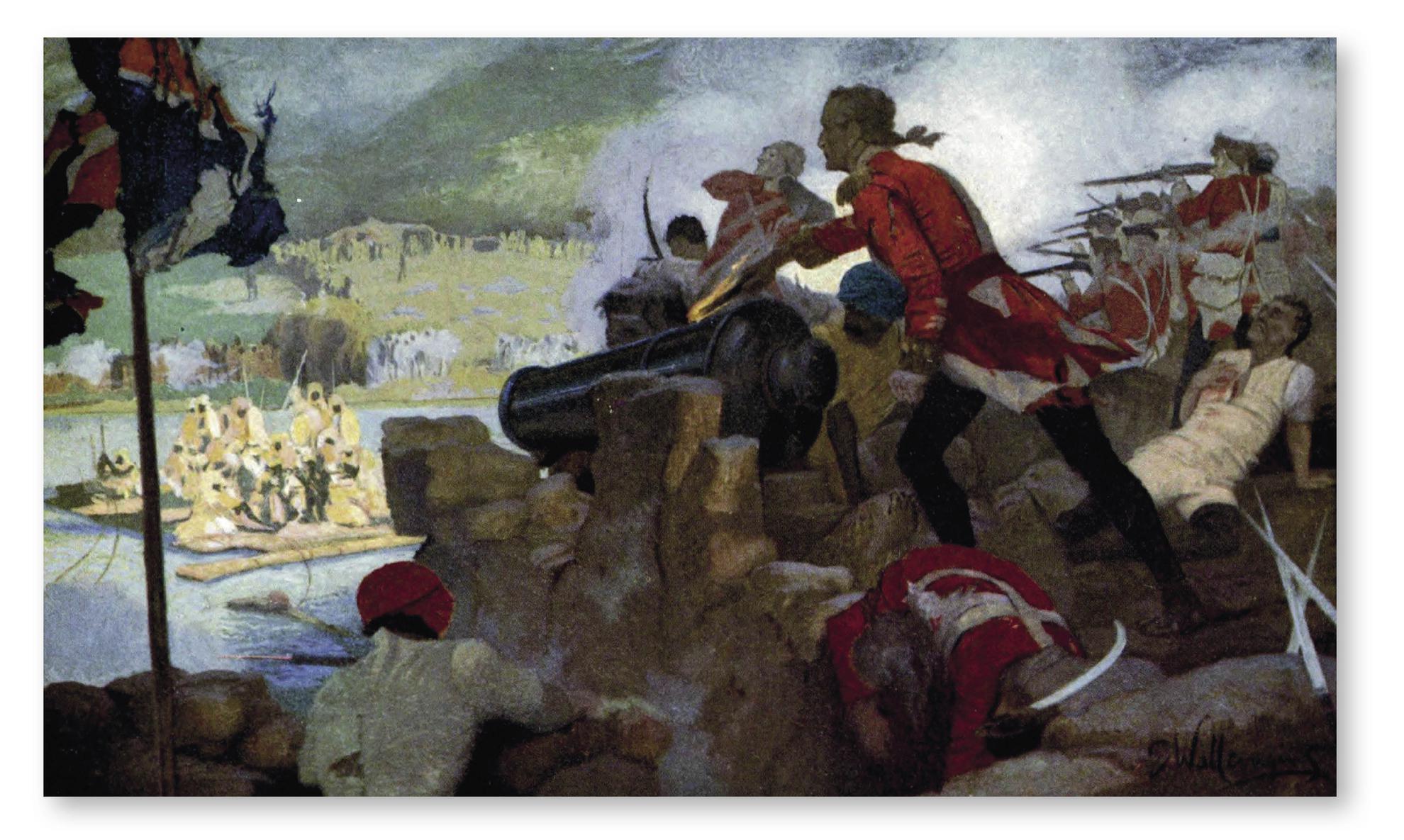

Under military commanders like Robert Clive (depicted here at the Siege of Arcot in 1751, in a painting by Ernest Wallcousins), the East India Company steadily exploited the power vacuum left by the collapse of the Mugh al Empire.

The Sikh court split into rival powers, the Dogra and Sikh factions, with the former built on a trio of Hindu brothers and the latter on the Sikh aristocracy itself, known as the Khalsa. The army, also often referred to as the Khalsa, saw an opportunity in this rivalry and began to play one side against the other, forcing the factions to court favour with the powerful armed forces of the state. As the soldiers continued to extort ever-higher wages from aspirants to the throne, payment became difficult if not impossible and disciple began to break down. Open defiance, the occasional murder of unpopular officers and even the looting of the civilian population became common. The British, with their hands full in Afghanistan, nevertheless noted with concern the growing instability in the Punjab.

The Tripartite Treaty of 1838, part of Britains interests in installing a puppet government in Afghanistan, had meant that Sikh soldiers actually fought alongside the British in that country. One general to earn distinction in this manner, Nao Nihal Singh, was the son of the ineffective Maharajah Kharak Singh (one of Ranjit Singhs seven sons and his designated successor). Nao Nihal Singh used his military prowess and good relationship with the British to take over the state from his father, and for a while it looked as if firm rule had been restored. In November 1840, a freak accident (some suspected foul play) returned the state to chaos: Nao Nihal Singh was killed by a falling beam while walking under an archway following his fathers funeral. Rival factions again formed behind two candidates for the throne. Sher Singh, another of Ranjit Singhs sons, was popular with the British, but it was Kharak Singhs widow, Chand Kaur, who was made maharani (empress), on 2 December 1840. A rather unpolished character, ill-equipped for the diplomatic duties her new position entailed, she was an unpopular ruler, despite being known as the Mai (mother).

Sher Singh was unwilling to accept this situation and began to actively undermine the Maharani. His principle method for achieving this was to promise higher wages to soldiers in the Sikh Army, which prompted many to desert to his camp. The British were uncomfortable with this development, and the growing instability it fostered, but were still preoccupied in Afghanistan. Recognizing Sher Singh as pro-British, support was therefore given to his bid for power. Emboldened, Sher Singh marched on Lahore, the seat of the Durbar (court), panicking the Maharani into offering lavish gifts to her remaining soldiers. Although happy to accept the gifts, the men recognized her actions as a symptom of fear and weakness, and continued to desert. By the time hostilities broke out, in January 1841, Sher Singh had 26,000 soldiers compared to just 5,000 for the Maharani, and two days of battle were enough to bring about the inevitable surrender. Chand Kaur had ruled for less than two months.