IMAGES

of America

LOS ANGELESS

CENTRAL

AVENUE JAZZ

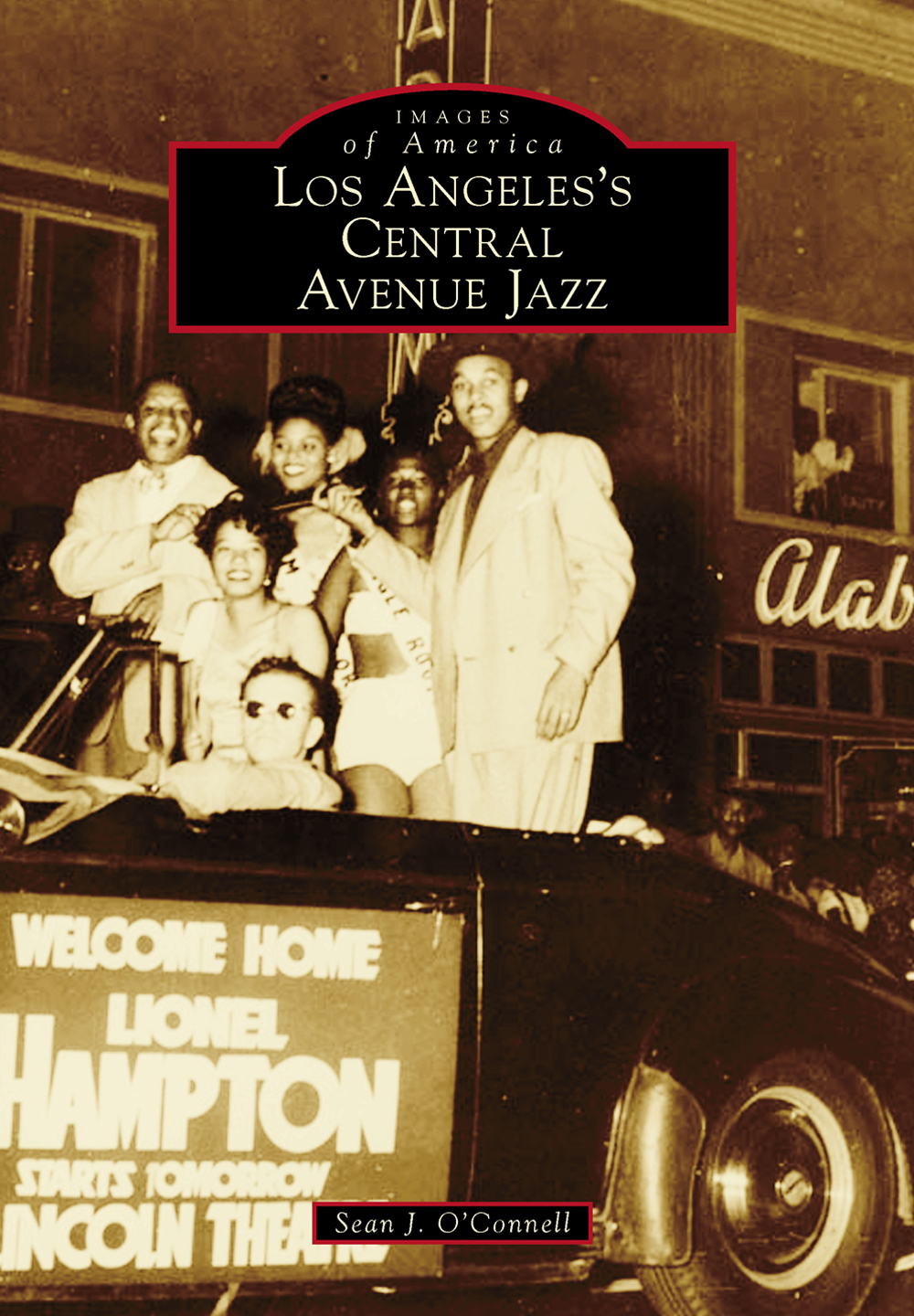

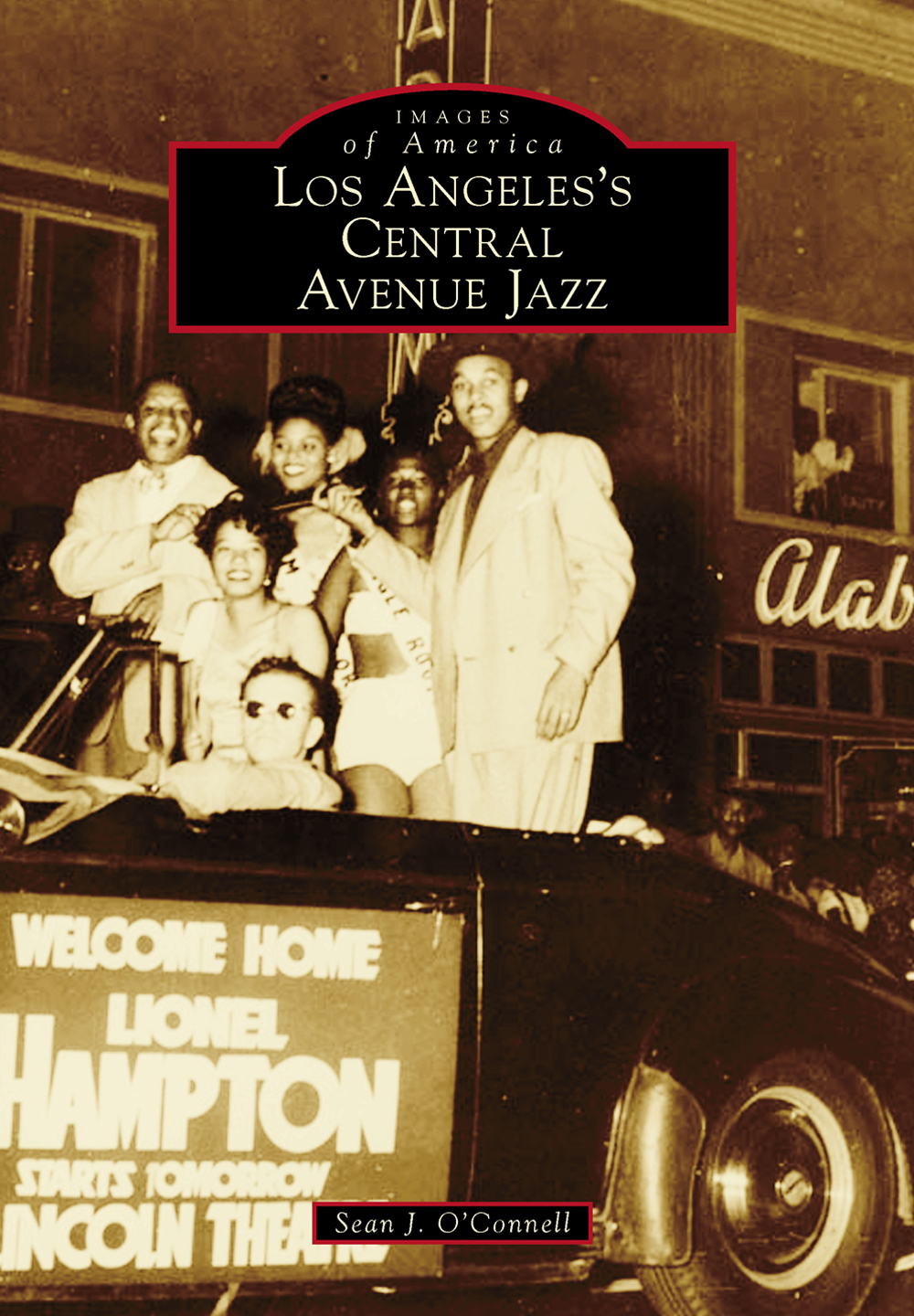

ON THE COVER: As the famed Club Alabam looms in the background, bandleader Lionel Hampton (left) greets a crowd of well-wishers at a parade in his honor on Central Avenue. The sign on the car notes his appearance the following day at the Lincoln Theater, which was 20 blocks to the north. Although he was not from Los Angeles and he did not live there long, his career got its biggest boost from the area, and he returned frequently. (Courtesy of the Shades of LA Collection, Los Angeles Public Library.)

IMAGES

of America

LOS ANGELESS

CENTRAL

AVENUE JAZZ

Sean J. OConnell

Copyright 2014 by Sean J. OConnell

ISBN 978-1-4671-3130-8

Ebook ISBN 9781439645369

Published by Arcadia Publishing

Charleston, South Carolina

Library of Congress Control Number: 2013947322

For all general information, please contact Arcadia Publishing:

Telephone 843-853-2070

Fax 843-853-0044

E-mail

For customer service and orders:

Toll-Free 1-888-313-2665

Visit us on the Internet at www.arcadiapublishing.com

To my wife Christina, who never imagined she would spend so much of her time listening to old-timey jazz.

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This book would not have been possible without the assistance of the jazz community in Los Angeles. Brick Wahl, James Janisse, Ken Poston, Joon Lee, Steven Isoardi, Ted Gioia, Armand Lewis, and Chris Barton have been instrumental in supporting the completion of this project. Nate Carter at the Dunbar Hotel opened up the newly renovated facility to me and pointed me in the direction of the spectacular roof view. Southern California libraries, including the Los Angeles Public Library, the USC Library, UCLA, and California State Northridge, are invaluable for their access to great snapshots from history. Check out their collections. My wife, Christina, has shown patience and support I could only dream of while we drove up and down Central Avenue looking for swinging ghosts (while my newborn daughter has served as a terrific editor between feedings, changings, and fits of tears). Most importantly, my parents, Fern and Dave, have always nurtured my interests in music and were always willing to take their teenage son to South Central to soak up a little culture.

Unless otherwise noted, all images are from the authors collection.

INTRODUCTION

Selling the Southern California lifestyle has never been particularly difficult. Sunshine and palm trees have lured millions to Los Angeles since the moment the city was incorporated in 1850. Its ceaseless sprawl has steadily spilled into the surrounding desert with the dubious promise of health and prosperity. For all those lucky enough to actually soak up the Pacific Ocean sunsets, there were twice as many denied that natural beauty in order to keep the illusion paved, electrified, and smelling of orange blossoms. Many of those optimistic transplants flocked to Los Angeles to escape the inhospitable climates of places like the American South only to find things were as rigidly segregated as anywhere else.

Los Angeles is composed of over 150 neighborhoods, many of them identifying themselves with one particular ethnic group. Some of these divisions were happily self-imposed while others were written into law. Central Avenue, which strikes like a dagger from downtown Los Angeles through Watts to northernmost Long Beach, was the strip allotted to African Americans, focusing primarily on a five-mile line between First Street in downtown and Slauson Avenue to the south. Due largely to restrictive covenant laws that allowed home owners to refuse sales to anyone whose color they did not approve, African Americans (both native and foreign) were confined to this narrow residential parcel, leaving few options in the nearly 500 square miles of Los Angeles county.

As a result, South Los Angeles was united solely by skin color with a diversity of educations, incomes, and aspirations changing from one home to the next. Doctors and lawyers lived next to dockworkers and janitors, and high-society opera singers borrowed sugar from barefoot bumpkins. The resulting cultural diversity led to a working-class, landlocked island alternative filled with hotels and nightclubs that hosted and nurtured some of the most significant jazz musicians of the 20th century.

The clich of beach bunnies and boardwalks was applied to all of Los Angeless exports. West Coast jazz was no exception, becoming synonymous with the scene at Hermosa Beachs famed Lighthouse and the sun-dappled swingers with saxophone cases full of sand and a year-round wardrobe of short-sleeve shirts and khakis. It was a predominantly Caucasian facade, and it took a lot away from the hard-edged innovators toiling away 24 hours a day in the backrooms of Central Avenue chicken joints. It may not have been as charming on the Avenue, but an honest and impassioned sound arose from the cramped venues that could rival New Orleans or New York in terms of forward-thinking musicianship.

As jazz rose from ragtime in the early 20th century, it learned to walk in the 1910s on the blood-splattered streets of New Orleanss Storyville. Musicians like Jelly Roll Morton, Kid Ory, and Louis Armstrong created a new musical language that was uniquely American and full of swing and inspired improvisation. When Storyville was closed with the battered end of a police baton in 1917, the musicians who were making a living there spread in every direction. Midwestern cities like Chicago and Kansas City inherited a few horn players while New York attracted a few more. Those uninterested in shoveling snow headed due west.

The most concentrated commercial strip of Central Avenue revolved around the Dunbar Hotel, which is on the corner of Forty-second Place. Built in 1928, it was originally known as the Hotel Somerville; however, the collapsing state of American economics caused ownership of the towering edifice to change hands by 1930, and it was renamed the Dunbar Hotel. Lodgings were not easy to come by for African Americans, but the Dunbar Hotel was African American friendly and catered to a high-class clientele. When Hollywood came knocking for jazz musicians, artists like Duke Ellington, Louis Armstrong, and Cab Calloway would haul their trunks down from the equally grandiose Union Station to set up at the Dunbar Hotel. On off nights, they would visit the dozens of clubs within walking distance of the lobby.

In the 1920s, Los Angeless African American population was less than 40,000. Cities like Watts and Compton were still farmland, and folks of every ethnicity could find a small parcel to call their own. By the 1940s, that population had doubled but the space remained the same. In 1945, alto saxophonist Charlie Parker arrived in Los Angeles for a nightclub stint, unaware that he would be spending the next year and a half of his short life in and around Central Avenue. He was welcomed with open arms by young modern jazz practitioners like pianist Hampton Hawes and trumpeter Howard McGhee, who brought him around to jam sessions and soaked up as much knowledge as Parkers deteriorating body could dispense.

Less than 10 years later, the Central Avenue scene had all but disappeared. After World War II ended, the booming defense industry in Southern California no longer needed to keep their plants running 24 hours a day. As a result, many African American employees were the first to be let go. Their cash-rich pockets quickly emptied, leaving entertainers low on the priority spending scale. In 1948, after years of fighting, restrictive covenants were repealed in Los Angeles, opening up a wide array of suburban options for those who could afford to escape the overcrowded confines of Central Avenue. Many of the wealthiest residents headed west for the vistas of Baldwin Hills, and numerous entertainment options followed them to streets like Western Avenue and Crenshaw Boulevard. Another civil rights victory, the amalgamation of the segregated musicians union, was finalized in 1953. The merger resulted in the closing of the Central Avenue musicians union, and that focus and fraternity shifted to the Hollywood offices. The rise of R&B and rock and roll further commandeered the record charts, and many jazz musicians were forced to adapt or lower their already dubious living standards.

Next page