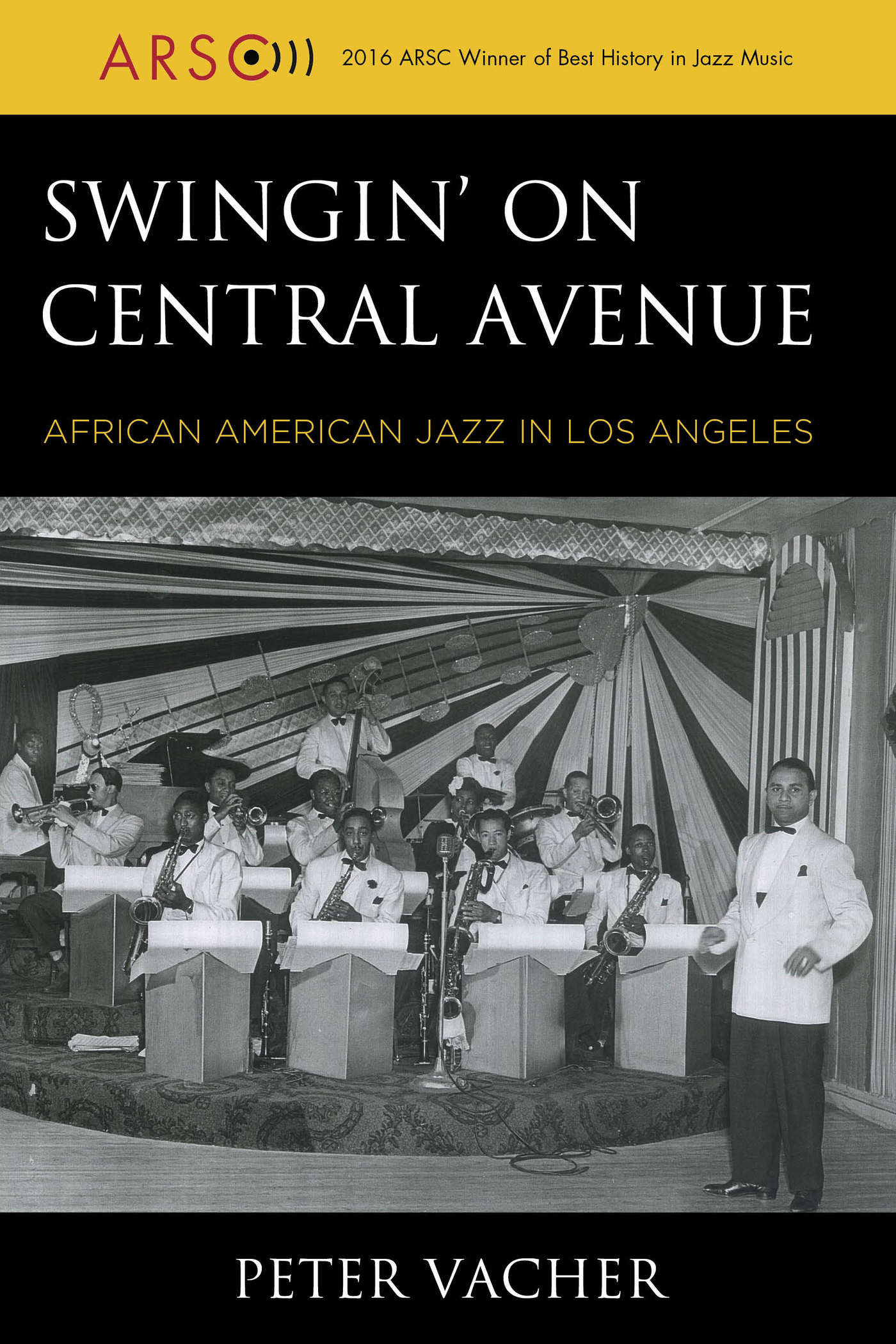

Swingin on Central Avenue

Swingin on Central Avenue

African American Jazz in Los Angeles

Peter Vacher

ROWMAN & LITTLEFIELD

Lanham Boulder New York London

Published by Rowman & Littlefield

A wholly owned subsidiary of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc.

4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706

www.rowman.com

Unit A, Whitacre Mews, 26-34 Stannary Street, London SE11 4AB

Copyright 2015 by Peter Vacher

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Vacher, Peter, 1937

Swingin on Central Avenue : African American jazz in Los Angeles / Peter Vacher.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-8108-8832-6 (hardcover : alk. paper)| ISBN 978-1-5381-1244-1 (pbk. : alk. paper) | ISBN 978-0-8108-8833-3 (ebook)

1. JazzCaliforniaLos Angeles19211930History and criticism. 2. JazzCaliforniaLos Angeles19311940History and criticism. 3. African American jazz musiciansCaliforniaLos AngelesInterviews. 4. Jazz musiciansCaliforniaLos AngelesInterviews. 5. Central Avenue (Los Angeles, Calif.). I. Title.

ML3508.8.L7V33 2015

781.650979494dc23

2015017034

TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

Printed in the United States of America

For my family and all my jazz friends, past and present.

Oral history is a great art when out of the individuality of personal experience we detect a common humanity or common purpose.Linda Grant

Sometimes ordinary speech is banal, and it is always repetitive, but if selected with art, it can reveal the inner life, often fantastic, concealed in the speaker.V. S. Pritchett

Jazz, at the time, was a major part of the average black persons life. As a community, we were much more aware of jazz than we are now. For example, most of the people on the street then knew who Charlie Parker was, but if you were to ask now, most people wouldnt know.

Billy Higgins, Los Angeles, 1984

Acknowledgments

Im especially grateful to the musicians who allowed me to delve into their lives and careers. They were invariably hospitable and patient in responding to my inquiries. Their wives and partners plied me with refreshments and often contributed informal comments that added valuably to these stories. Above all, they were tolerant enough to overlook my ignorance and to forgive my lack of preparation. They lent me photographs and other ephemera, content to trust this stranger who had arrived on their doorsteps. Some stayed in touch by mail and telephone.

My friends Roger and Zoila Jamieson and attorney Bob Allen allowed me to camp out with them in Long Beach and Baldwin Hills, respectively, putting me up and driving me to appointments. They fed me and gave me the run of their homes. However often I pressed them to come over to London so that I could return their hospitality, they demurred. California seems like the best of places when youre there, I guess.

Others who helped by providing supportive information, leads, and photographs include the late Helen and Joe Darensbourg (who hosted me for several weeks while we were working on his autobiography); the late Harold Kaye for his generosity in sharing vital photographs and data relating to jazz in Hawaii; Franz Hoffman for his invaluable research into the black press; Steve Simon of the Fanchon and Marco Archive; Laura Risk and Anthony Barnett for their Ginger Smock expertise; the writer and LA expert Kirk Silsbee; the late Otto Flckiger for sharing his collection of Red Mack photographs; the always willing Howard Rye who made his unpublished research on African American musicians in China and Japan available to me, along with data supplied by Robert Ford; the gospel music historian Opal Louis Nations, who let me have scans of photographs of Monte Easter and Norman Bowden; Gary Lasley of Local 47 AFM and their archivist, Andrew Morris, who dug into the remaining files relating to the now defunct black Local 767; my long-term friend, the photo collector Theo Zwicky; researchers Bob Eagle and Eric LeBlanc; the Swedish researcher Bo Scherman, who gave me access to his interview with Betty Hall Jones; Steve Isoardi who opened his files; and retired drummer Dick Shanahan.

Im also especially grateful to Tad Hershorn of the Institute of Jazz Studies at Rutgers University for his help with picture research and the provision of images. The same goes for Kelly P. McEniry of the University of MissouriKansas City University Library, which houses the Buck Clayton Collection, who found and supplied key images relating to Claytons time in Shanghai.

Mark Cantor, Bruce Raeburn, Dave Bennett, Derek Coller, trumpeter Clora Bryant, bandleader/composer Gerald Wilson, Ernie Garside, Dan Barrett, saxophonists Vi Redd and the late Jackie Kelso, Danny Gugolz, Mark Berresford, the late Jean-Pierre Battestini, the late Ray Avery, Malcolm Walker, Tony Shoppee, bassist Bernard Carrere, the late Floyd Levin, and the late bebop drummer Roy Porter all gave willingly of their recollections and helped with photographs and leads.

Anne Bennett, Mick Beazley, and Peter Ryan applied their expertise to reproducing photographs and Im especially grateful to them too. All the photographs that accompany the text are from the authors collection, unless otherwise noted.

Finally, I should thank Ed Berger of the Institute of Jazz Studies at Rutgers University for his initial interest and Bennett Graff at Scarecrow for his patience and faith in the project.

As ever, my wife, Patricia Vacher, was hugely supportive and understanding.

Introduction

It would be all too easy to dismiss these African American jazz stories as inconsequential and mundane. After all, none of the musicians gained international fame or achieved much more than local celebrity. Their recordings were largely low-key and, in some cases, frustratingly few. Most stayed close to home once they had settled in Los Angeles or its surrounding area. Only a handful ever toured in Europe more than once or moved regularly beyond Californias confines, although Caughey Roberts Jr. did travel to Shanghai, China, in the 1930s and Andy Blakeney and Monk McFay worked in Hawaii for a significant period.

You could cast them as the journeymen of jazz: black Americans whose career trajectories took in territory dance bands in the South, theater and cabaret orchestras, minstrel shows, swing combos, rhythm and blues groups, and in some cases revivalist New Orleans music. You could also say that they represent the gamut of localized black music experience but largely excluding bebop and modern jazz. And its in their precise placement in time that I believe their reminiscences have merit. Most of these players were centered in the pre-bop jazz world when swing was very much the thing and entertainment values mattered even when times were tough. Theirs are essentially untold stories, for only a few were ever interviewed and never at this length or with this amount of attendant pictorial material.

Next page

TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.