CONTENTS

This book is dedicated to

Mayor Andy Baxter and to the memory of his beloved wife,

Carley Cunniff, in modest token of my gratitude for

their support, encouragement, and invaluable friendship

ILLUSTRATION CAPTIONS

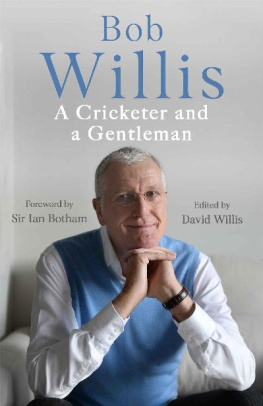

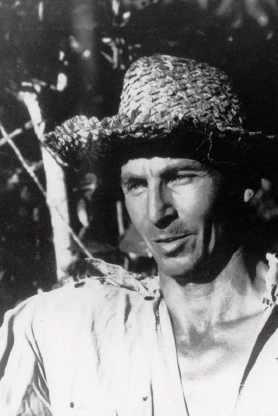

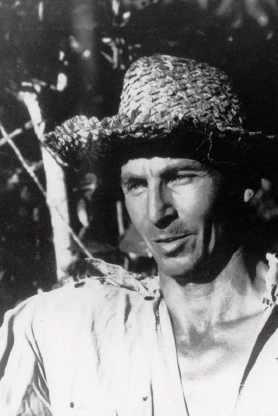

Frontispiece: A haggard Willis aboard the Coast Guard cutter Ingham, 1966.

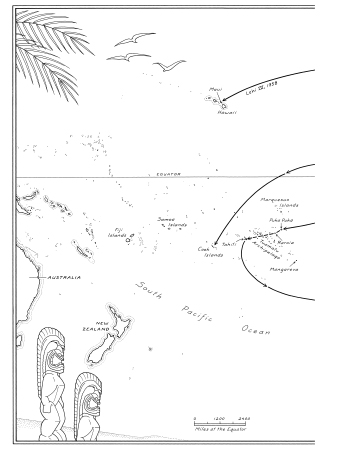

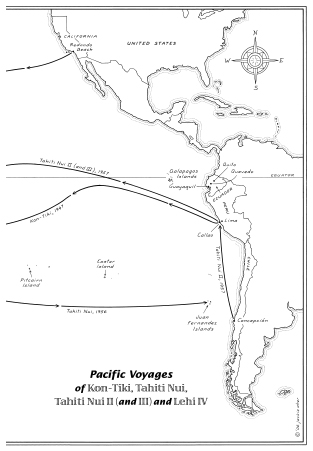

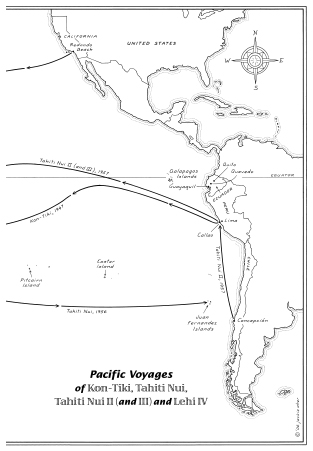

Front Matter: Pacific voyages of Kon-Tiki, Tahiti Nui, Tahiti Nui II (and III), and Lihi IV.

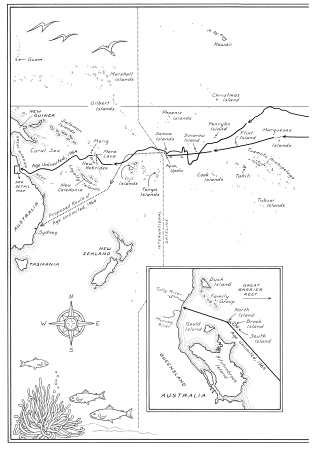

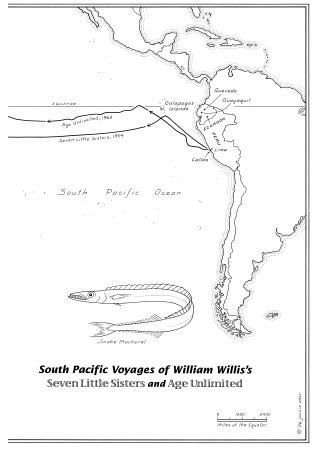

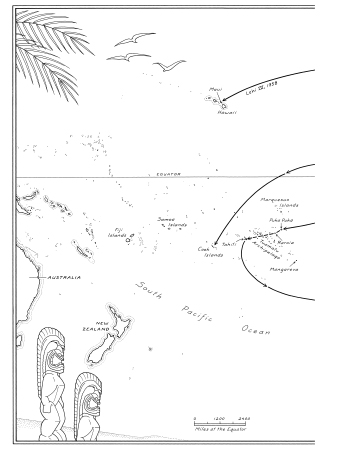

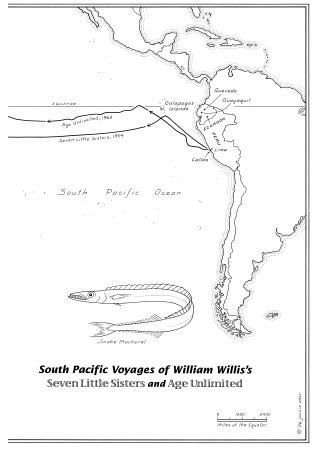

Front Matter: South Pacific voyages of William Williss Seven Little Sisters and Age Unlimited.

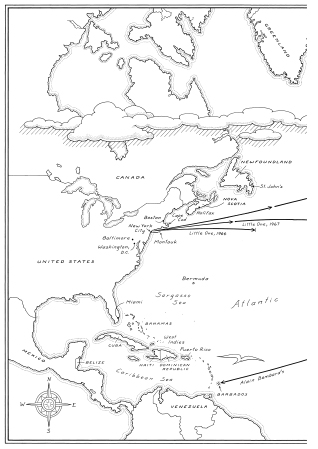

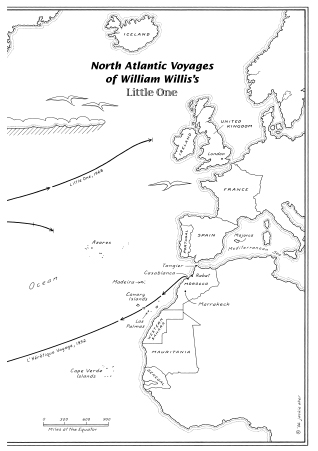

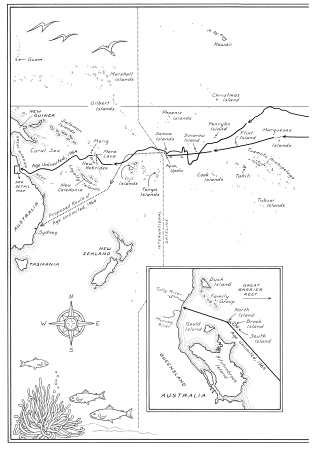

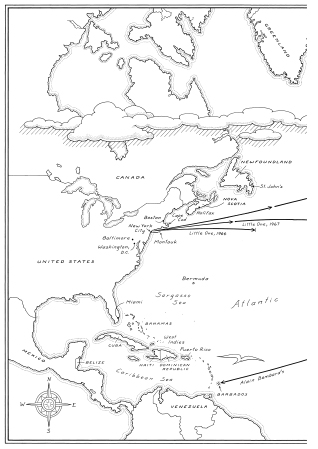

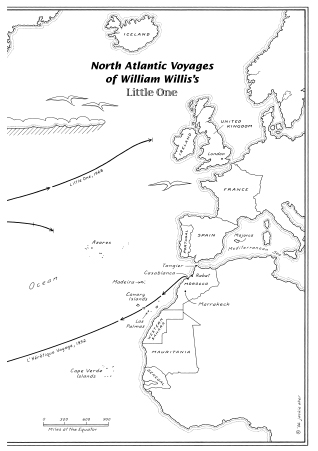

Front Matter: North Atlantic voyages of Willam Williss Little One.

Front Matter: Rigging on the Age Unlimited (drawings by Willis).

Front Matter: Willis in convict garb, 1938.

Chapter 2: Willis ties the lashings of the Seven Little Sisters, 1954.

Chapter 3: The Age Unlimited leaves Callao Harbor under tow, 1963.

Chapter 4: The Seven Little Sisters under way, 1954.

Chapter 5: Cans of fresh water stowed below deck on the Seven Little Sisters, 1954.

Chapter 6: Willis in the galley of the Age Unlimited, 1963.

Chapter 7: Hernia relief (drawing by Willis).

Chapter 8: The Age Unlimited aground off Samoa, 1963.

Chapter 9: Willis, with Teddy, receiving the Certificate of Masterful Seamanship for his Age Unlimited crossing from the president of The Maritime Union of America, 1965.

Chapter 10: Willis in the cabin of Little One, 1968.

Chapter 11: Little One under tow on the East River, New York, 1966.

Mainsail, jib, mizzen

Mainsail, extra mainsail, two mizzens

Mainsail, extra mainsail, staysail, mizzen

Two mainsails, one wingsail, two mizzens

Two mainsails, two wingsails (seen from bow)

Little One

HE CARRIED BY WAY of provisions only olive oil and flour, honey and lemon juice, garlic and evaporated milk. Since he intended to drink from the sea, a personal practice of long standing, hed dispensed with the bother of stowing so much as the first ounce of fresh water. His radar reflector was a scrap of planking wrapped in aluminum foil, his chronometer a balky pocketwatch, his distress flag a scarlet sweater. Hed shipped no proper radio, had but a sextant for his bearings, sailing directions to guide him into the English Channel past Bishop Rock. Among his papers was a letter of introduction to the mayor of Plymouth, England, from the Honorable John V. Lindsay, the mayor of New York City. It read, in part, If the bearer delivers this letter to you in person, he will have completed a trans-Atlantic voyage of great merit.

This was his third attempt in as many years at a single-handed crossing of the Atlantic Ocean, all in a craft hed christened Little One in honor of his wife. Hardly more than a glorified dinghy, that boat lived decidedly down to her name. She was eleven and a half feet stem to stern and five feet at the beam. She was sloop-rigged and lone-masted, weighed just over one thousand pounds, had three feet of draft, and was, even in sheltered, benign waters, ungainly.

Hed departed on his maiden voyage directly out of New York Harbor. A tug had taken his boat in tow at the foot of Twenty-third Street and had hauled him down the East River and along the Brooklyn shoreline in a bid to avoid both shipping traffic and bothersome harbor chop. Hed cast himself loose just a couple of miles past the Verrazano Narrows Bridge and had passed his first evening at sea watching the sun set over New Jersey while enjoying for dinner two teaspoons of whole wheat flour moistened with spit.

His first week out, the winds were southerly and the sea fog was persistent. He fell overboard one morning while attempting to set his jib, fairly swamped the boat in the process, and doused everything hed carried. (He was never entirely dry for the remainder of the trip.) On the open ocean, Little One rolled more violently than hed expected. She bucked and wallowed and generally handled in the manner of a cork, which, when combined with the gloomy weather, rendered his sextant all but useless. He either couldnt see the sun or was too sea-tossed to shoot a useful sight and so had, as a rule, no reliable sense of just where he might be.

Ordinarily, he could have expected to need three months on the water to reach the English Channel from the narrows of Lower New York Bay, but he was plagued by unfavorable weathera string of gales, and a hurricaneand after five weeks at sea, he found himself off the coast of Nova Scotia, within sight of Sable Island and in some danger from the surf. He was nearly two hundred miles farther north than hed intended and well west of where hed reasonably hoped to be.

Steering south, he met with the Black Swan, a freighter bound for Antwerp, and was given a carton of fresh fruit that he welcomed aboard for ballast. He took to riding out storms by nailing himself in under his canvas decking, which salt and sun had conspired to spoil the fit of early on. Hed lie with a knife in hand in case he met cause to slash his way out. He slept little, was awake for days at a time, and compensated with meditation, along with a form of rhythmic breathing hed freely adapted from Eastern religion. He could be, on occasion, so strict in its practice and parsimonious with air that he would rhythmically breathe himself into a faint. He was once unconscious for two days running, and, having survived somehow adrift, he awoke to find his chronometer stopped because hed failed to wind it.

Next page