CONTENTS

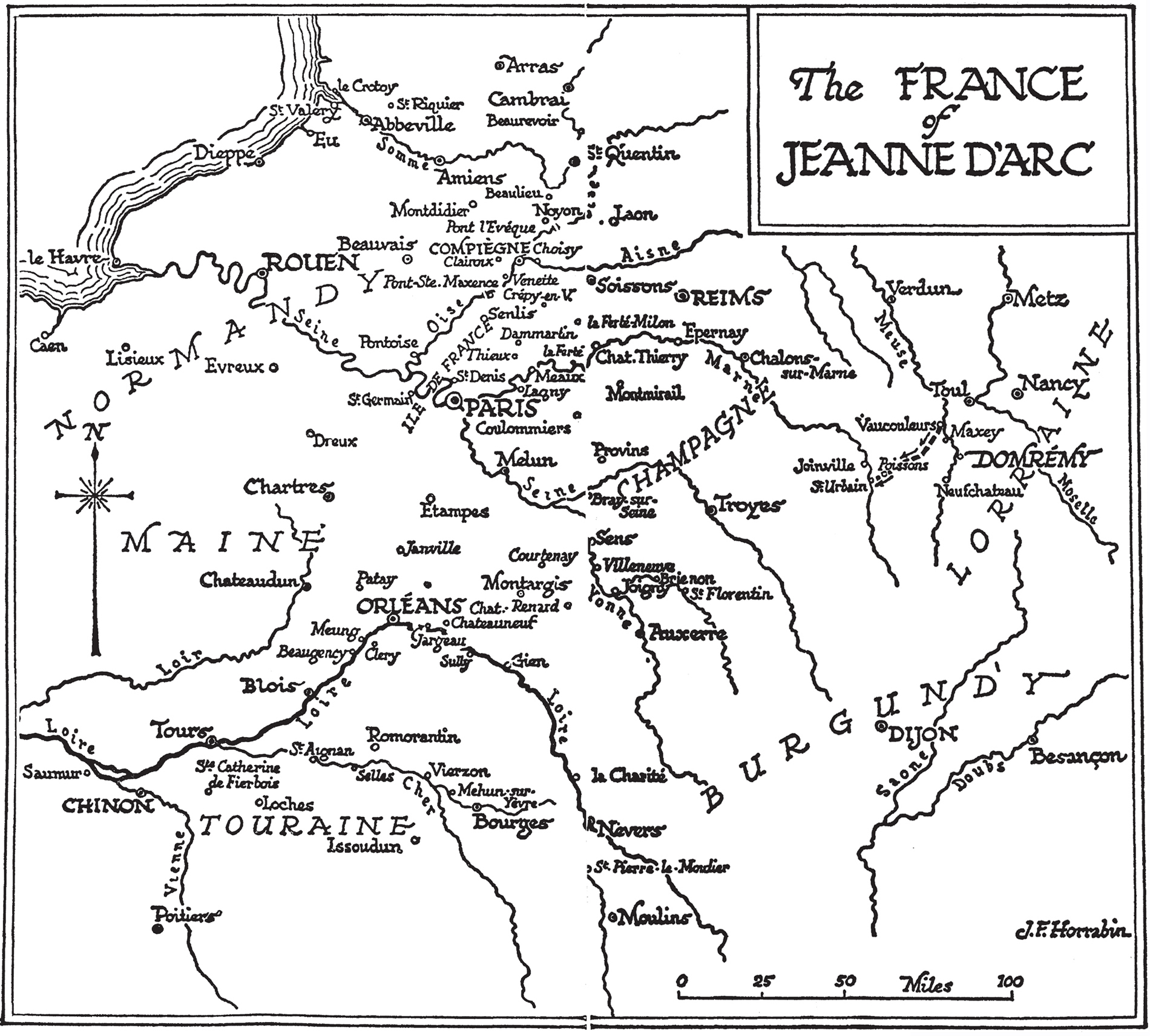

MAPS (by J. F. Horrabin)

ABOUT THE BOOK

The strange story of Joan of Arc, the obscure peasant girl who became the national saint of France, is retold in this celebrated, classic biography. Saint Joan lives for the reader on every page, as a shepherd girl in a remote part of fifteenth-century rural France, visited by visions of saints and angels; as the avenging virgin who regenerated the soul of a torn and wretched France and led her troops to victory; and as a condemned heretic and witch, burned at the stake and, five hundred years later, canonised as a saint.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Victoria Mary Sackville-West, known as Vita, was born in 1892 at Knole in Kent, the only child of aristocratic parents. In 1913 she married diplomat Harold Nicolson, with whom she had two sons and travelled extensively before settling at Sissinghurst Castle in 1930, where she devoted much of her time to creating its now world-famous garden. Throughout her life Sackville-West had a number of other relationships with both men and women, and her unconventional marriage would later become the subject of a biography written by her son Nigel Nicolson. Though she produced a substantial body of work, amongst which are writings on travel and gardening, Sackville-West is best known for her novels The Edwardians (1930) and All Passion Spent (1931), and for the pastoral poem The Land (1926) which was awarded the prestigious Hawthornden Prize. She died in 1962 at Sissinghurst.

ALSO BY VITA SACKVILLE-WEST

Novels

Family History

Heritage

The Dragon in Shallow Waters

The Heir

Challenge

Seducers in Ecuador

The Edwardians

All Passion Spent

Grand Canyon

Non-Fiction

Passenger to Teheran

English Country Houses

Pepita

The Eagle and The Dove

Sissinghurst: The Creation of a Garden

For PHILIPPA

[And it was shown to her] how serious and dangerous it is curiously to examine the things which are beyond ones understanding, and to believe in new things and even to invent new and unusual things, for demons have a way of introducing themselves into such-like curiosities.

ADMONITION ADDRESSED TO JOAN OF ARC.

Procs de condamnation, Vol. 1, p. 390.

Pauvre Jeanne dArc! Elle a eu bien du malheur dans ce que sa mmoire a provoqu dcrits et de compositions de diverses sortes.

SAINTE BEUVE.

FOREWORD

There are many deliberate omissions in this book.

Students of the period may ask why I have not entered more closely into such things as the relations between the Dukes of Burgundy, Brittany, Bedford, and Gloucester, Cardinal Beaufort, and so on.

My answer is that I wished to concentrate on Joan of Arc herself, bringing in the minimum of outside politics.

It seemed to me that Joan of Arc was far more important and problematical than any of the figures or politics which surrounded her. It became necessary for me to refer to some of those figures and politics: but, beyond that simplified reference, I have kept her consistently in the foreground, at the expense of other interests. It seemed to me, in short, that Joan of Arc presented a fundamental problem of the deepest importance, whereas the political difficulties of her day presented only a topical and therefore secondary interest. The history of France in the fifteenth century can hold no interest today save for the scholar; the strange career of Joan of Arc, on the other hand, remains a story whose conclusion is as yet unfound. I do not claim to have found it in this book. I take the view that many years, possibly hundreds of years, may elapse before it is found at all.

In the meantime, I wish to record my gratitude to several people: to my sister-in-law, Gwen St. Levan, who provided and annotated many specialised books for me; to Mr J. F. Horrabin, who drew the maps; to Father Herbert Thurston, S.J., who gave me his time for discussion of Saint Joan; to Dr Baines for his views on the psychology of visionaries; to Mr Milton Waldman, who most generously lent me his notes on the trial; and to the Secretary of the Royal Observatory, Greenwich, who sent me a table of the phases of the moon during 1429 and 1430.

The question of footnotes troubled me considerably. I had at first intended to put none, but was gradually forced to the conclusion that a complete absence of reference to authorities was even more irritating to the reader than the constant check to the progress of his reading. Of two evils, I hope I have chosen the less.

The question of proper names troubled me also. It seemed to me that Jeanne was ill-translated by Joan, and yet I could not bring myself to write the closer rendering of Jean. I therefore decided to stick to the French version of her name throughout, except in the title of the book itself.

An analogous problem arose over the names of French cities. It will be observed that I have elected to print Orleans without an accent on the e. This is because most English readers are accustomed to pronounce Orleans in the English way. On the other hand, I have spelt Reims in the French way. This is because the addition of an h in no way affects the pronunciation, and therefore seemed to me pointless.

I am advised on good authority that Domremy should be written without an accent on the e.

V. S.-W.

Et Jehanne, la bonne Lorraine,

Qu Englois bruslrent Rouan:

O sont-elles, Vierge souveraine?

Mais o sont les neiges dantan!

FRANOIS VILLON

1. JEANNE DARC

I

No contemporary portrait of Jeanne dArc is known to exist. Possibly none ever existed at all. She denied having ever sat for her portrait, although she admitted having seen, at Arras, a painting of herself in full armour, kneeling on one knee, presenting a letter to the King. This painting, she affirmed, was the work of a Scotsman. Apart from that, she said she had never seen another image in her likeness, nor had she ever caused one to be made. The frescoes depicting her life, which Montaigne saw on the faade of her home at Domremy on his way to Italy a hundred and forty-nine years after her death, were already in a bad state by then and have now entirely disappeared; lge, he wrote, en a fort corrompu la peinture. Yet there can be no question that she was, even during her lifetime, a person whom one would expect to find portrayed in a hundred different places; a person of legend. Butterflies in clouds accompanied her standard; pigeons miraculously fluttered towards her; men fell into rivers and were drowned; dead babies yawned and came to life; flocks of little birds perched on bushes to watch her making war. There is nothing left to tell us what Jeanne dArc looked like, although Euglide, Princess of Hungary, gives us some reason to believe that she had a short neck and a little bright red mark behind her right ear.

II

On the other hand, hundreds of posthumous representations, in stone, in bronze, in plaster, in stained glass, in fresco, on canvas, or on wood, leave us with an impression neither blurred nor doubtful but only too definite and precise. Pen and ink, equally active, have lent their services to the willing imagination, so that from these various mediums of the artist and the historian a double image clearly emerges: the image of Jeanne pensive and pastoral, or the image of Jeanne embattled and heroic, the basis of truth in both interpretations heavily overlaid with all the hues of sentimentality and romance. If these interpreters are to be believed, then Jeanne the shepherdess sat permanently with folded hands and upturned eyes, and Jeanne the captain permanently bestrode a charger whose forelegs never touched the ground. The lover of truth sighs in vain for one plain portrait, unflattering, authentic, crude; a portrait which shall attempt no picturesque rendering of that remarkable destiny, no seizing of those dramatic moments, but a quiet statement of what Jeanne looked like, whether in daily life at her fathers house, or in the few strenuous months when by popular acclaim she became known throughout France and much of Europe as a suddenly public personage; as, in short, la Pucelle,