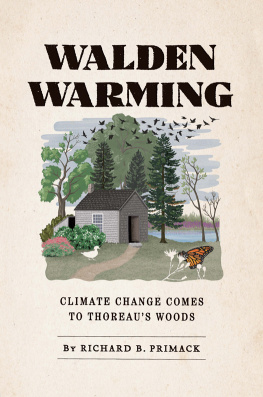

Walden Warming

CLIMATE CHANGE COMES TO THOREAUS WOODS

Richard B. Primack

The University of Chicago Press

Chicago & London

RICHARD B. PRIMACK is professor of biology at Boston University. He is the author of Essentials of Conservation Biology and A Primer of Conservation Biology and coauthor of Tropical Rain Forests: An Ecological and Biogeographical Comparison.

The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637

The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London

2014 by The University of Chicago

All rights reserved. Published 2014.

Printed in the United States of America

23 22 21 20 19 18 17 16 15 14 1 2 3 4 5

ISBN -13: 978-0-226-68268-6 (cloth)

ISBN -13: 978-0-226-06221-1 (e-book)

DOI : 10.7208/chicago/9780226062211.001.0001

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Primack, Richard B., 1950 author.

Walden warming: climate change comes to Thoreaus woods / Richard B. Primack.

pages; cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-226-68268-6 (cloth: alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-226-06221-1 (e-book) 1. PlantsEffect of global warming onMassachusettsWalden Pond State Reservation. 2. AnimalsEffect of global warming onMassachusettsWalden Pond State Reservation. 3. PlantsEffect of global warming onMassachusettsConcord. 4. AnimalsEffect of global warming onMassachusettsConcord. 5. Climatic changesMassachusettsWalden Pond State Reservation. 6. Climatic changesMassachusettsConcord. 7. Thoreau, Henry David, 18171862. I. Title.

QH 105. M 4 P 75 2014

577.2709744dc23 2013038942

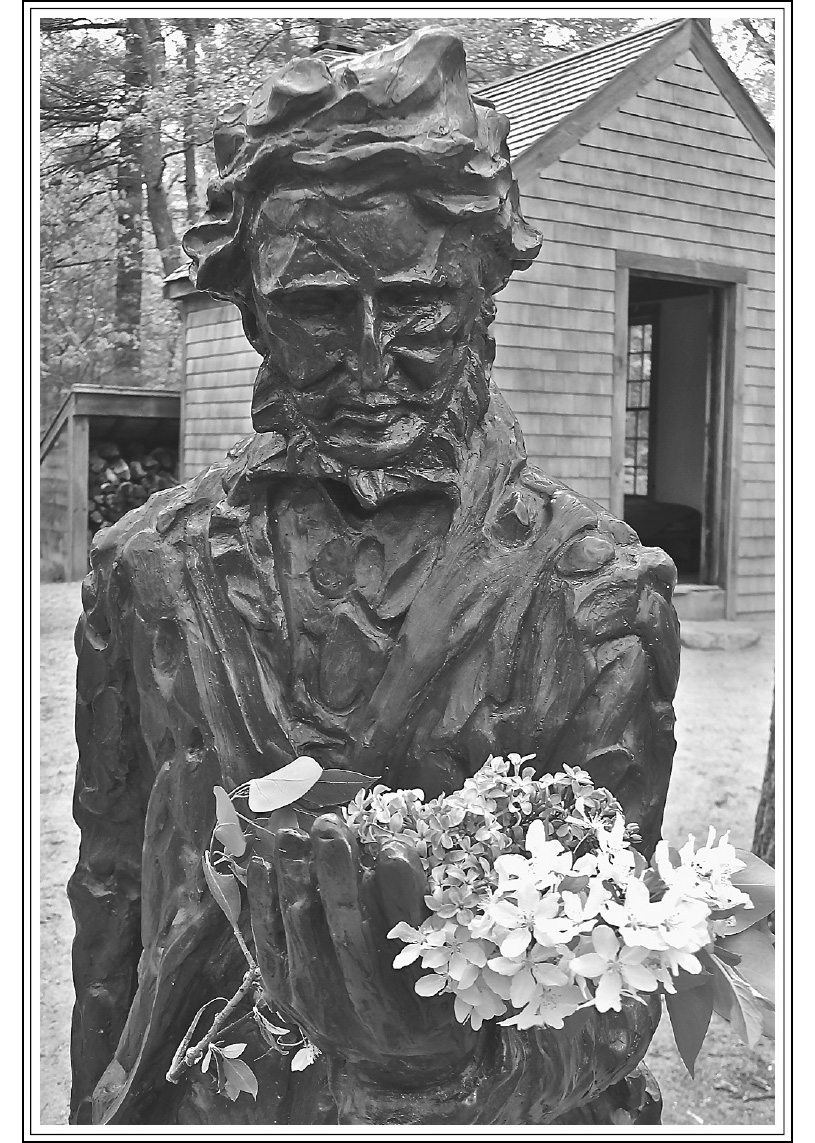

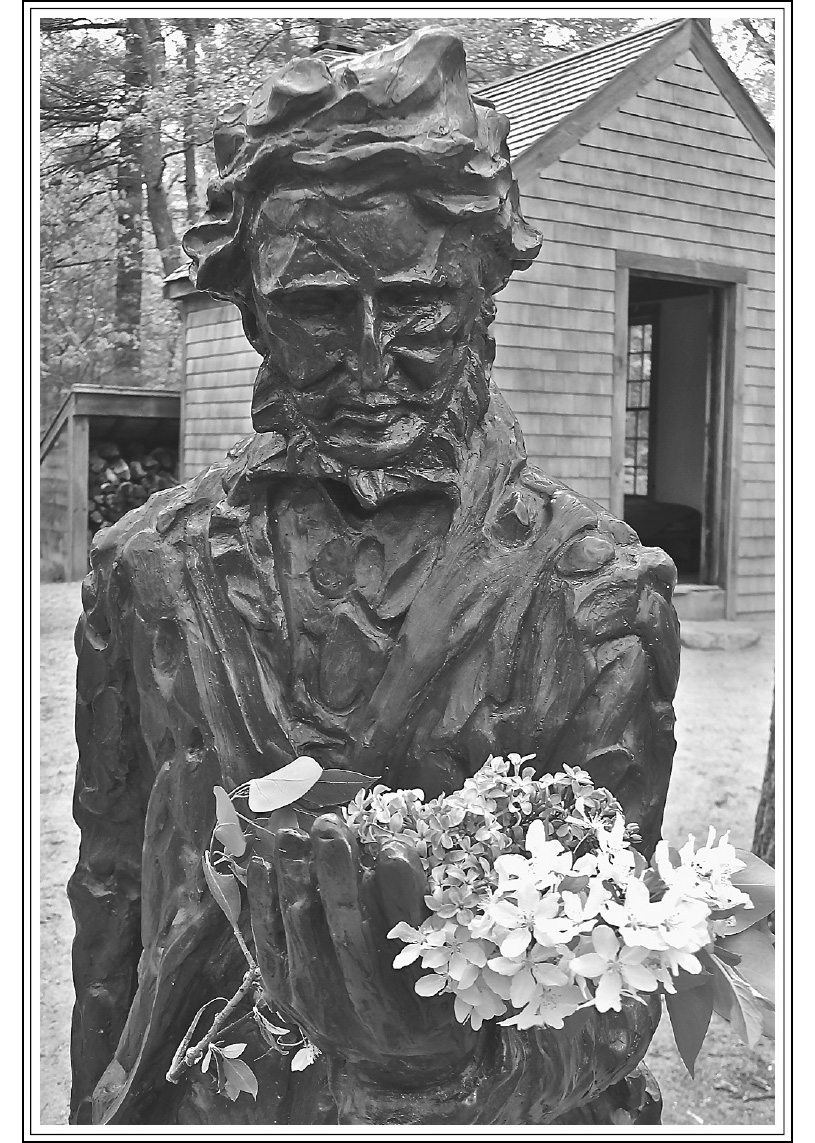

Frontispiece: Statue of Henry David Thoreau in front of a replica of his cabin on the edge of Walden Pond; photo by Richard B. Primack and Abraham J. Miller-Rushing.

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992

(Permanence of Paper).

Contents

I wish so to live ever as to derive my satisfactions and inspirations from the commonest events, every-day phenomena, so that what my senses hourly perceive, my daily walk, the conversation of my neighbors, may inspire me, and I may dream of no heaven but that which lies about me.

THE JOURNAL OF HENRY DAVID THOREAU , MARCH 11, 1856

EVERY SPRING FOR THE PAST ELEVEN YEARS , I have walked around Walden Pond and other places in Concord, Massachusetts, recording the first blooming dates for all of the wildflowers. I am repeating the same observations made a century and half ago by the author and philosopher Henry David Thoreau. On May 11, 1853, Thoreau recorded the first open flower of highbush blueberry. Its distinctive white tubular flowers are easy to observe. In subsequent years, he recorded the first blueberry flowers in Concord between May 14 and 19.

If Thoreau went looking for the first blueberry flowers of Concord in mid-May today, he would be too latesome bushes would be covered with flowers, while others would have only a few stragglers left hanging among the young green fruits. Since the 1850s, the first blueberry flowering has shifted three weeks earlierthey now generally open during the last two weeks of April. However, in 2012, after a record warm winter, blueberry bushes began to flower on April 1, six weeks earlier than in Thoreaus time. When a historical perspective is combined with modern observations, one thing becomes clear: climate change has come to Walden Pond.

By the late 1980s, I and many other biologists began to see that our world was being transformed and often severely degraded by human activities. I increasingly came to believe that botanists, wildlife ecologists, and other field naturalists should use their knowledge of the living world to help preserve those wild species of plants and animals that do so much to lend beauty and grace to our human existence, and that provide food, timber, medicine, and ecosystem services that are essential to human well-being. So I switched from researching the ecology of plants and animals in undisturbed natural areas to documenting human impacts on the diversity of the living world and finding ways to conserve and restore the species and ecosystems that remain. During the 1990s, this meant studying and writing about the effects of logging on the island of Borneo. But beginning in 2002, I made another second significant shift in my career. I decided to apply my knowledge of plants and natural history to an examination of the effect of warming temperatures and other aspects of climate change on plants and animals.

I soon learned that Thoreau and other naturalists had observed the plants and animals of Massachusetts, and these observations could be updated and reanalyzed to gain perspective on the impacts of a warming climate. I even came to regard Thoreau as a scientific colleague and considered adding his name as a coauthor to my research publications. This book describes my adventures with my students and colleagues as we studied the local effects of a warming climate, building upon the foundation established by Thoreau.

Richard B. Primack

Boston University, 2014

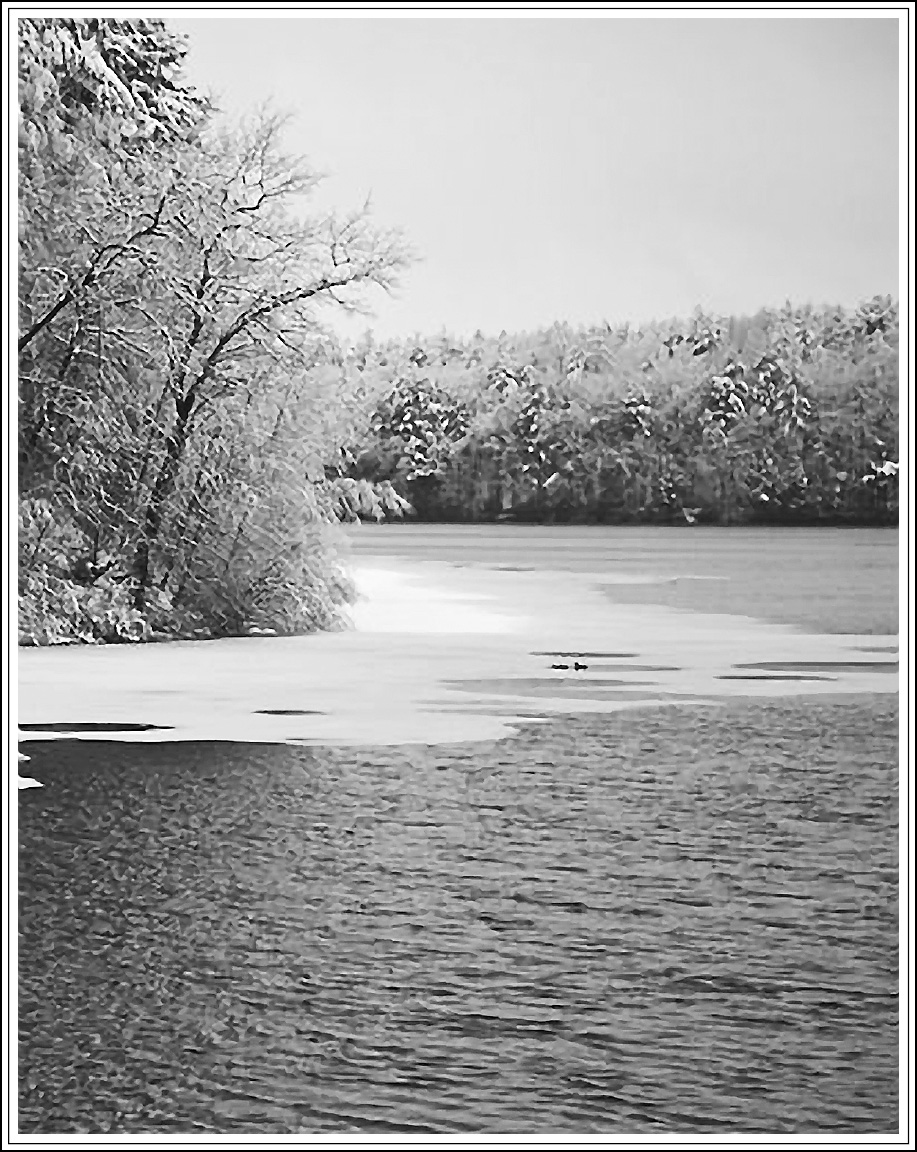

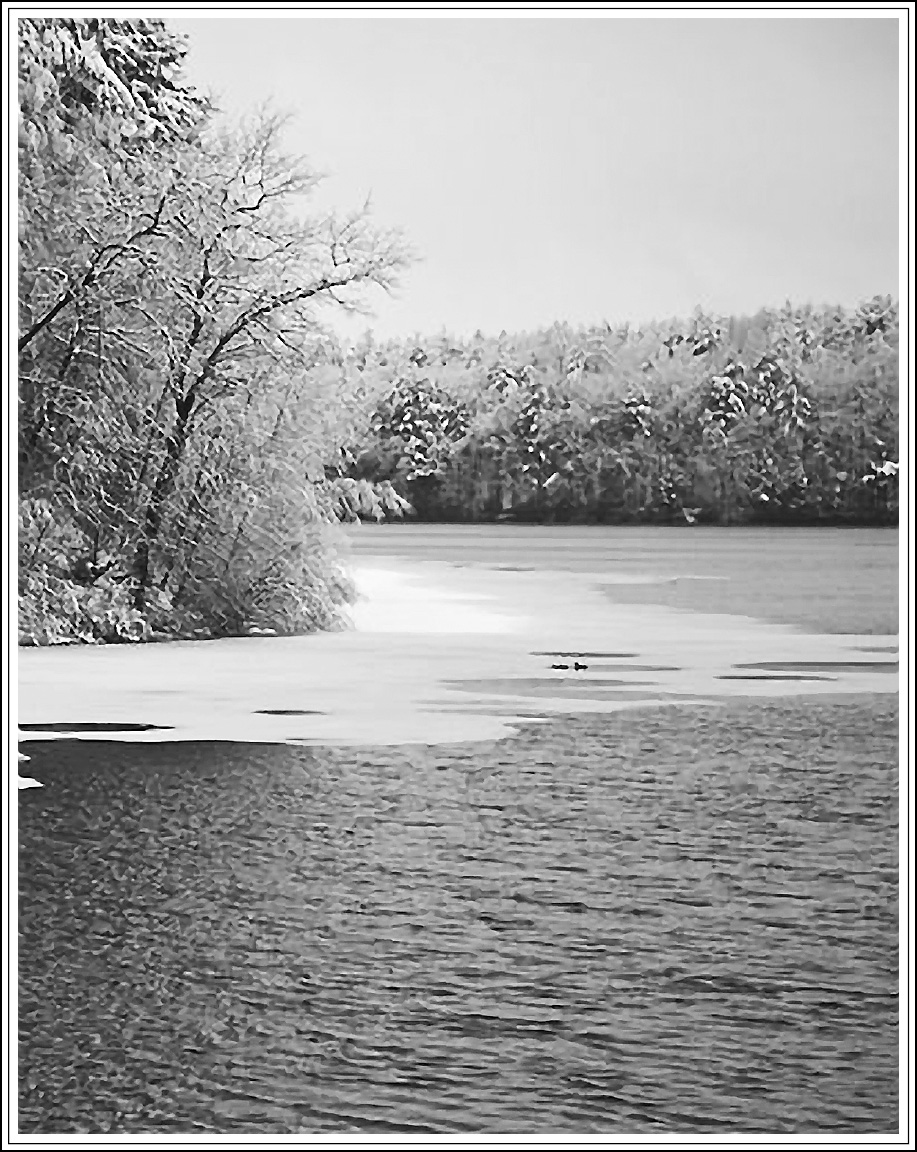

Ice-out at Walden Pond; photo by Tim Laman.

I frequently tramped eight or ten miles through the deepest snow to keep an appointment with a beech-tree, or a yellow birch, or an old acquaintance among the pines.

THOREAU, WALDEN

. Borneo to Boston

IN 2001, I WAS CONDUCTING FIELDWORK IN Bako National Park, a rugged rain forest landscape of jagged rocks and cliffs on the northwest seacoast of Malaysian Borneo. I was studying how hundreds of different trees could coexist in a single stand in the rain forest and the ways that selective logging was affecting both the mix of species and the structure of the forest. Trees were my focus, but a spectacular variety of animals and herbaceous plants confronted me at every turn. Each morning as I set out from the field station, I could hear large proboscis monkeys calling and moving through the forest canopy above me; rattan vines cascaded down from the trees; and fallen flowers and leaves of great variety littered the forest floor. However, even though Bako National Park was a paradise for a nature-lover like myself, it was impossible for me to ignore the reality that all around the park, as well as up and down the whole island, the forest was vanishing. It was being cleared to harvest timber and to make way for palm-oil plantations.

IN 2001, I WAS CONDUCTING FIELDWORK IN Bako National Park, a rugged rain forest landscape of jagged rocks and cliffs on the northwest seacoast of Malaysian Borneo. I was studying how hundreds of different trees could coexist in a single stand in the rain forest and the ways that selective logging was affecting both the mix of species and the structure of the forest. Trees were my focus, but a spectacular variety of animals and herbaceous plants confronted me at every turn. Each morning as I set out from the field station, I could hear large proboscis monkeys calling and moving through the forest canopy above me; rattan vines cascaded down from the trees; and fallen flowers and leaves of great variety littered the forest floor. However, even though Bako National Park was a paradise for a nature-lover like myself, it was impossible for me to ignore the reality that all around the park, as well as up and down the whole island, the forest was vanishing. It was being cleared to harvest timber and to make way for palm-oil plantations.

The clearing of rain forests in Borneo and across the Old and New World tropics is having devastating consequences for biodiversity, but the destruction of tropical forests around the globe is hastening a different kind of change: climate change. Rain forests fix carbonthey are among the largest carbon reservoirs on the planetand when people clear and burn them, tons of carbon dioxide are released into the atmosphere. People can understand how habitat destruction leads to the loss of orangutans, hummingbirds, and orchids. But what they dont understand as well is how clearing trees in Borneo and the Amazon can affect climate on the other side of the world. Increasingly, as I measured trees and patrolled study plots, it was climate change that was on my mind.

Next page

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992

IN 2001, I WAS CONDUCTING FIELDWORK IN Bako National Park, a rugged rain forest landscape of jagged rocks and cliffs on the northwest seacoast of Malaysian Borneo. I was studying how hundreds of different trees could coexist in a single stand in the rain forest and the ways that selective logging was affecting both the mix of species and the structure of the forest. Trees were my focus, but a spectacular variety of animals and herbaceous plants confronted me at every turn. Each morning as I set out from the field station, I could hear large proboscis monkeys calling and moving through the forest canopy above me; rattan vines cascaded down from the trees; and fallen flowers and leaves of great variety littered the forest floor. However, even though Bako National Park was a paradise for a nature-lover like myself, it was impossible for me to ignore the reality that all around the park, as well as up and down the whole island, the forest was vanishing. It was being cleared to harvest timber and to make way for palm-oil plantations.

IN 2001, I WAS CONDUCTING FIELDWORK IN Bako National Park, a rugged rain forest landscape of jagged rocks and cliffs on the northwest seacoast of Malaysian Borneo. I was studying how hundreds of different trees could coexist in a single stand in the rain forest and the ways that selective logging was affecting both the mix of species and the structure of the forest. Trees were my focus, but a spectacular variety of animals and herbaceous plants confronted me at every turn. Each morning as I set out from the field station, I could hear large proboscis monkeys calling and moving through the forest canopy above me; rattan vines cascaded down from the trees; and fallen flowers and leaves of great variety littered the forest floor. However, even though Bako National Park was a paradise for a nature-lover like myself, it was impossible for me to ignore the reality that all around the park, as well as up and down the whole island, the forest was vanishing. It was being cleared to harvest timber and to make way for palm-oil plantations.