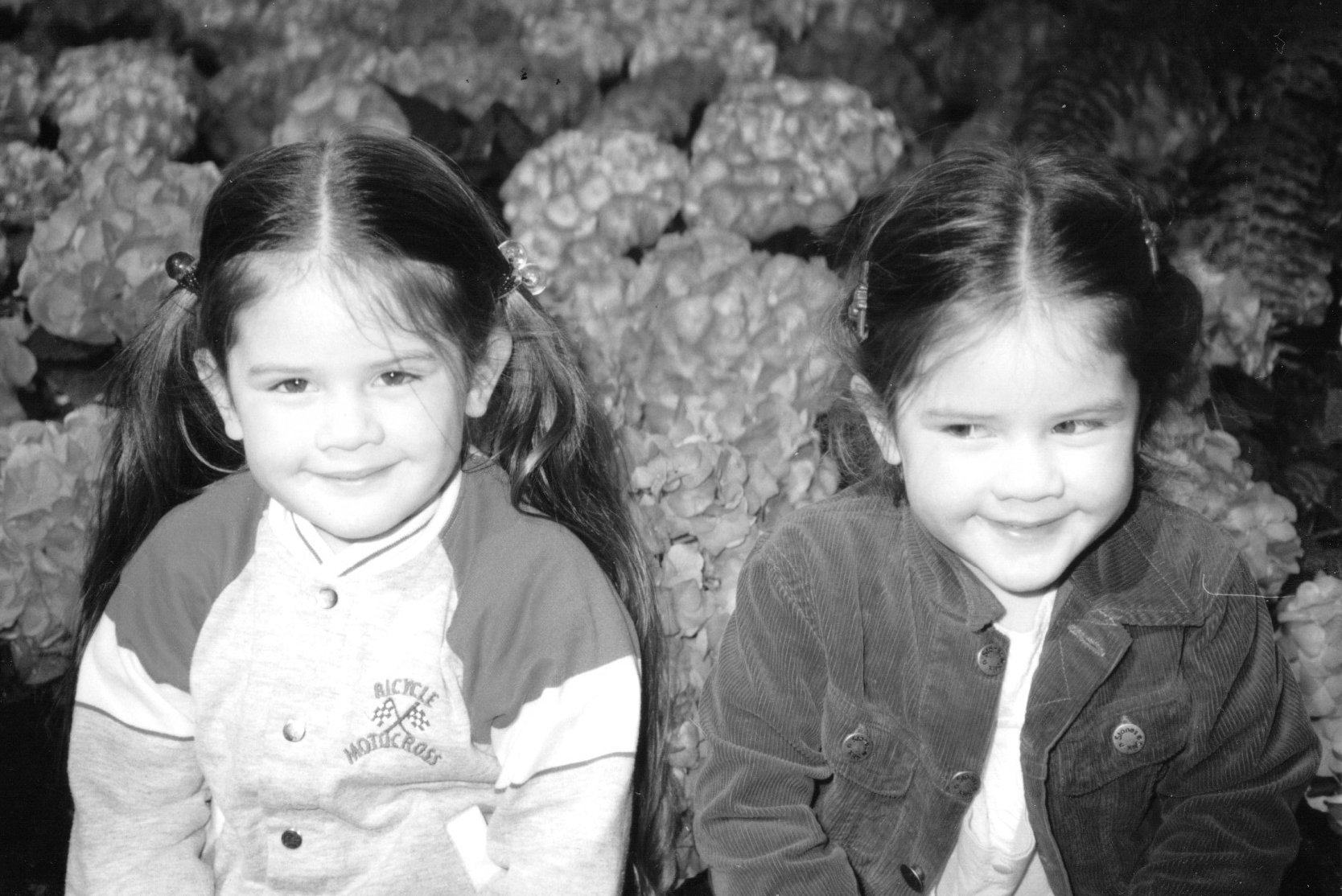

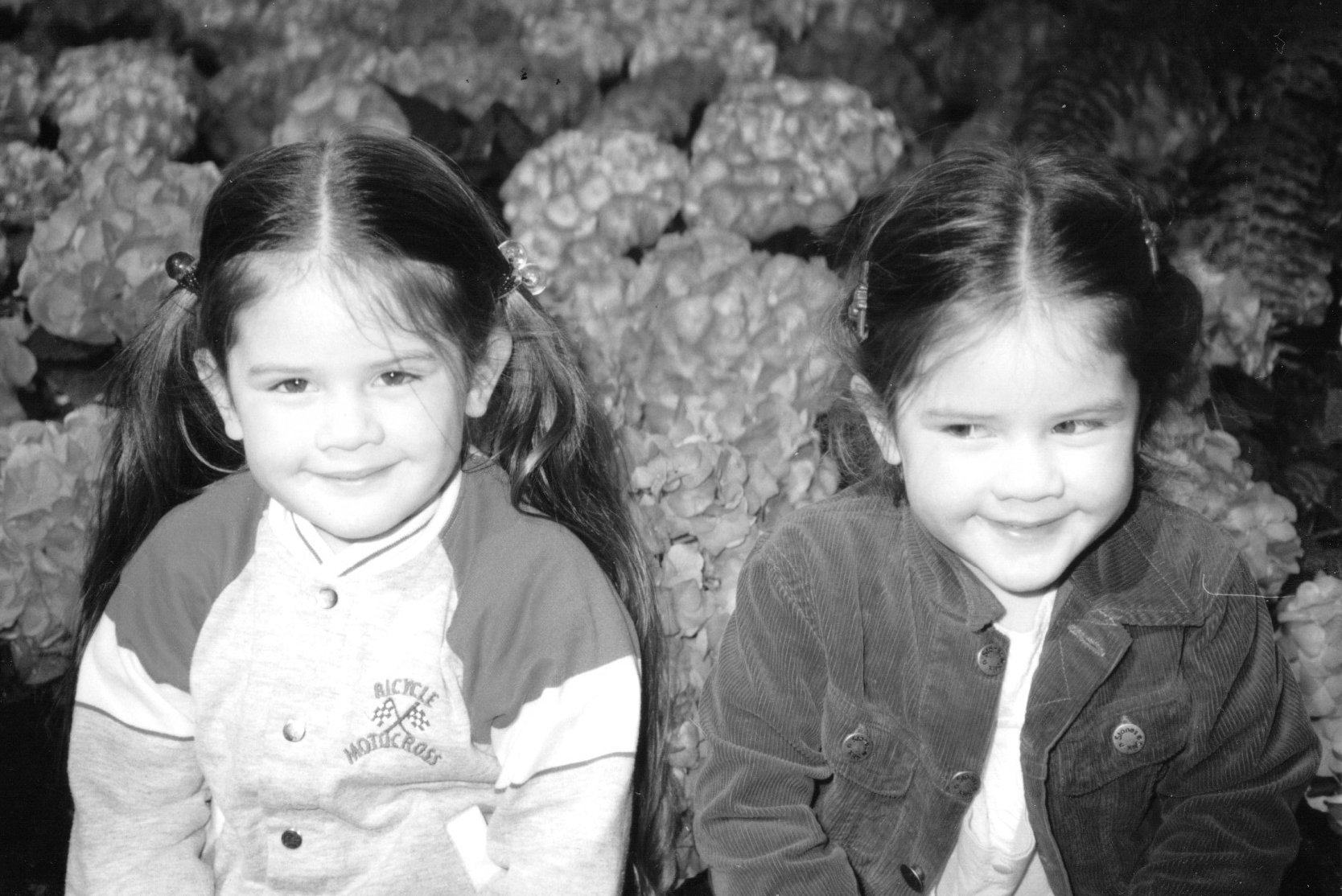

I have no visual memory of Tegan before we were four years old. There is proof of her existence: scores of photographs of us posed together on couches, sitting on laps, or standing side by side in our cribs. But the snapshots in my mind contain no trace of her. What I can summon is the feeling of her. As if she existed everywhere, and in everything.

In preschool, a lump was found in her left arm that required surgery. We were separated for the first time since birth. On the first day of her hospital stay, I was left in the care of another woman with a set of twins, the same age as Tegan and me. While her children played together, I sat on the floor of their bedroom, stunned by my sisters absence. On the second day, I lay on our grandmothers living room couch with a fever. Opposite me, I registered the empty space.

When we were three years old, Sara suffered from a bout of night terrors. I have a vivid memory during that time of her flat out on her back, in the hallway outside her bedroom, her pajamaed limbs flailing, and my parents on either side of her trying to calm her down. In the memory, I am reassured by my mom and dad that Sara is okay, that everything is fine. But I am left uneasy, unsettled.

When I shared this memory years later, my mom and dad were quick to correct me: it was me who suffered from the terrible dreams all those years ago, and Sara who watched from her bedroom at the end of the hall. I have it backward, they insist.

I wonder frequently how many of the memories I carry of Sara are actually my own. How much of my early life have I confused with hers? Our tangled nature makes even me feel interchangeable with Saraindistinguishable, bound, and suffocated. There is often a violent urge in me to tear those early memories of us apart, even if just in my own head. But I admit, there is also great comfort that comes from traveling through life with a witness, an identical twin to corroborate your version of things.

Imagine the map of Canada. If you placed your finger on the Pacific Ocean just north of the U.S. border and dragged it east across the Rocky Mountains until the topography flattened out and the states of Idaho and Montana were stacked below, youd find the city of Calgary sprouting between the foothills and prairie of Alberta. In the 1970s an oil boom doubled the citys population and sent skyscrapers shooting up along the bank of the Bow River. The cold mountain water sliced the wealthy western quadrants into north and south before it converged with the Elbow River, vertically splitting the citys southeast side in two. Beyond the suburban sprawl was a sea of mustard yellow farmland thick with barley, and in every direction a sky blue as the ocean. From September to early June, temperatures dipped as low as minus thirty degrees Celsius and snowstorms buried entire streets of cars under snowbanks frozen like waves in midcurl. When the chinook winds from the west raised normally frigid temperatures above freezing, people swarmed the streets in short sleeves. The summers came and went quickly, and the long, desert-dry days were broken up by storms that rolled in from the south and the east in cinematic scope. Hailstorms of golf ballsize ice exploded windshields, split foreheads, and dented cars. The sun didnt set until 10:00 p.m.

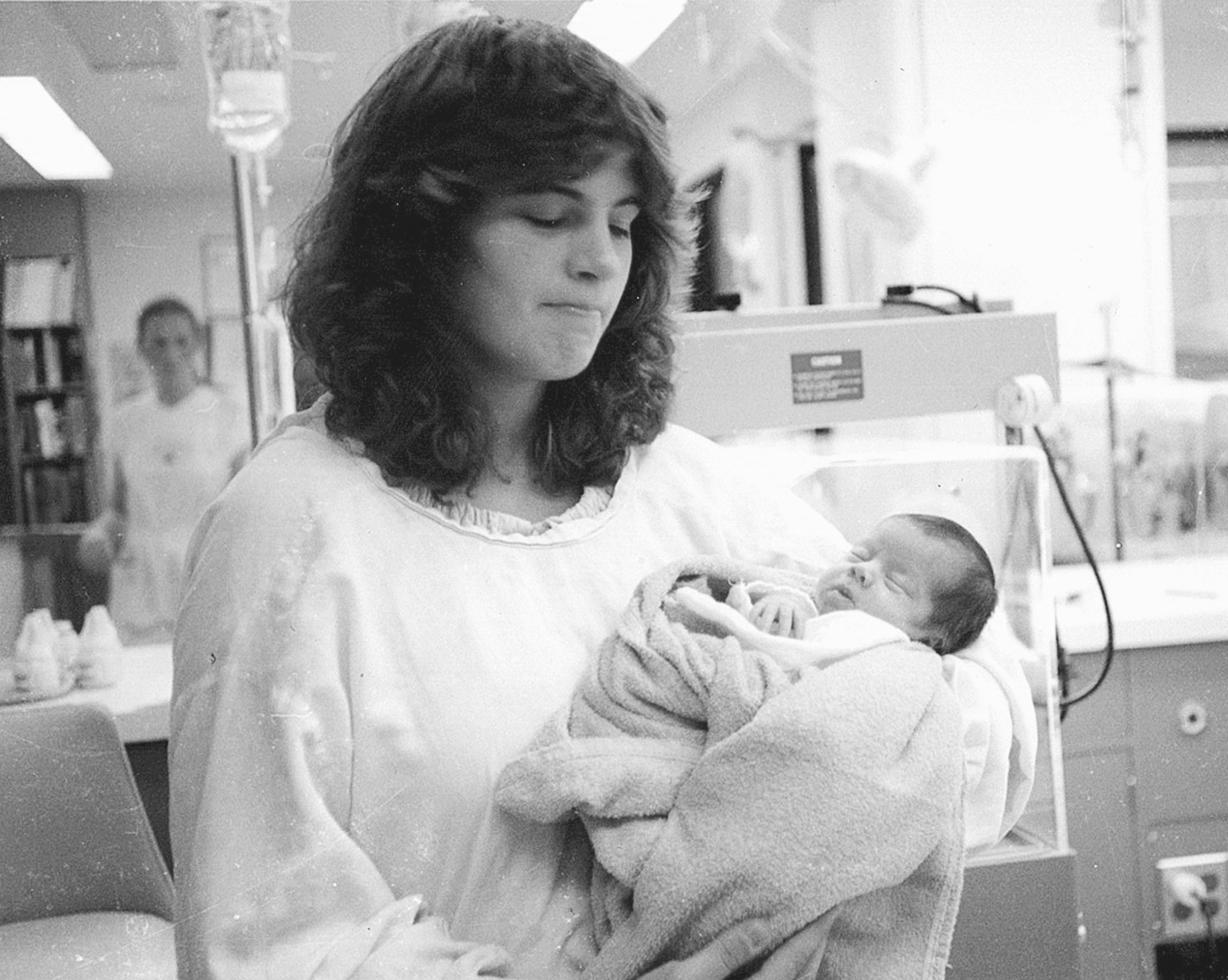

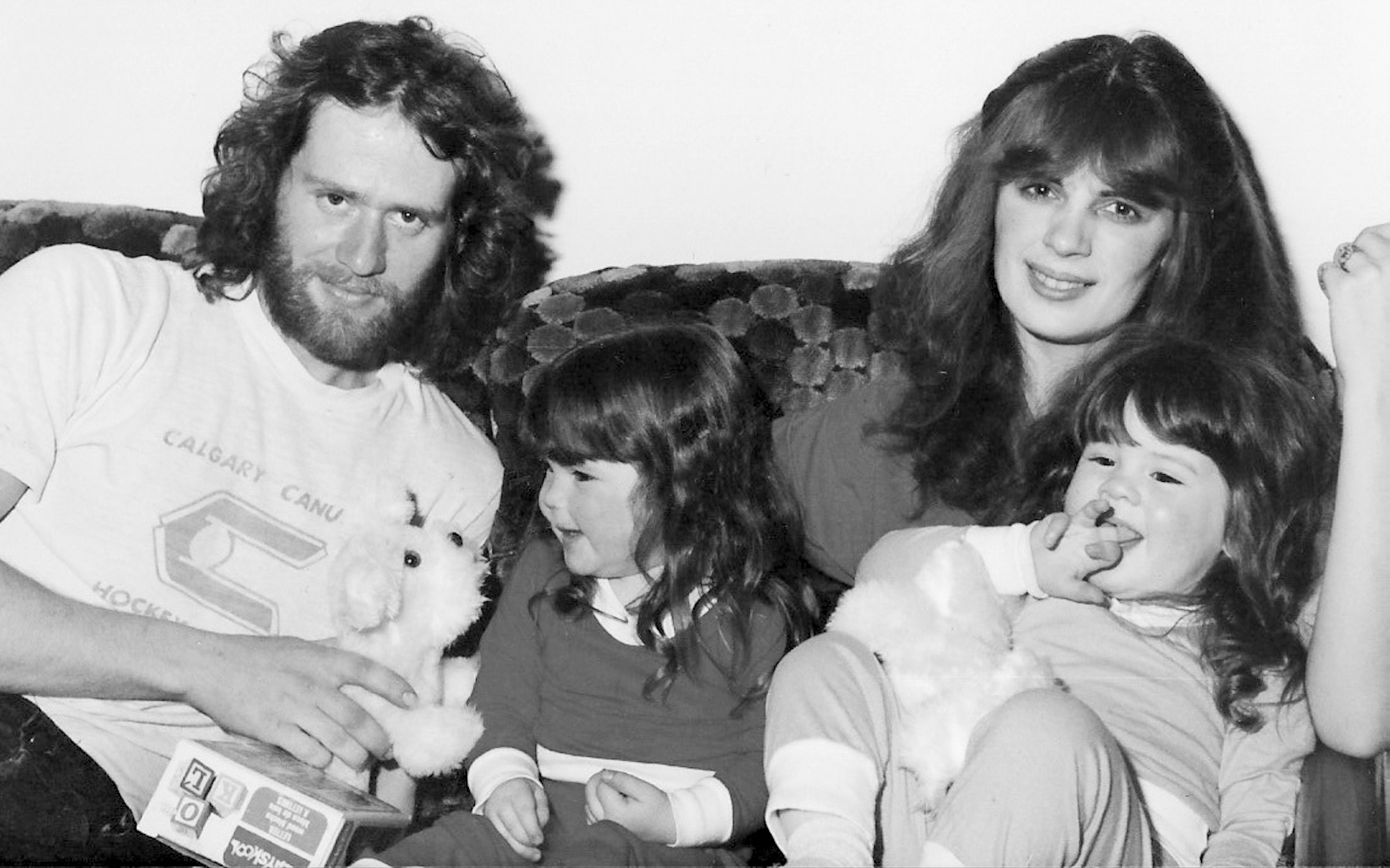

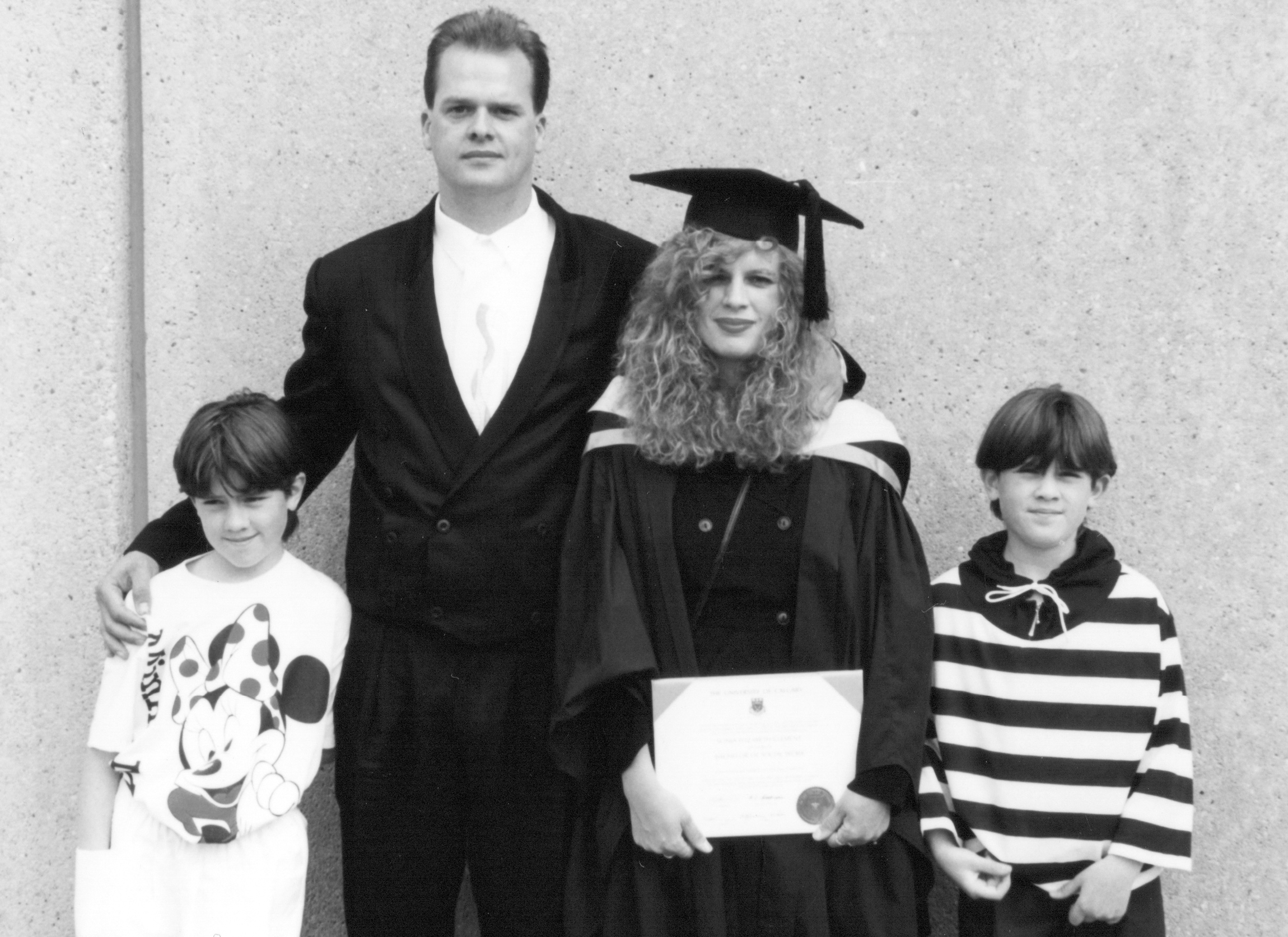

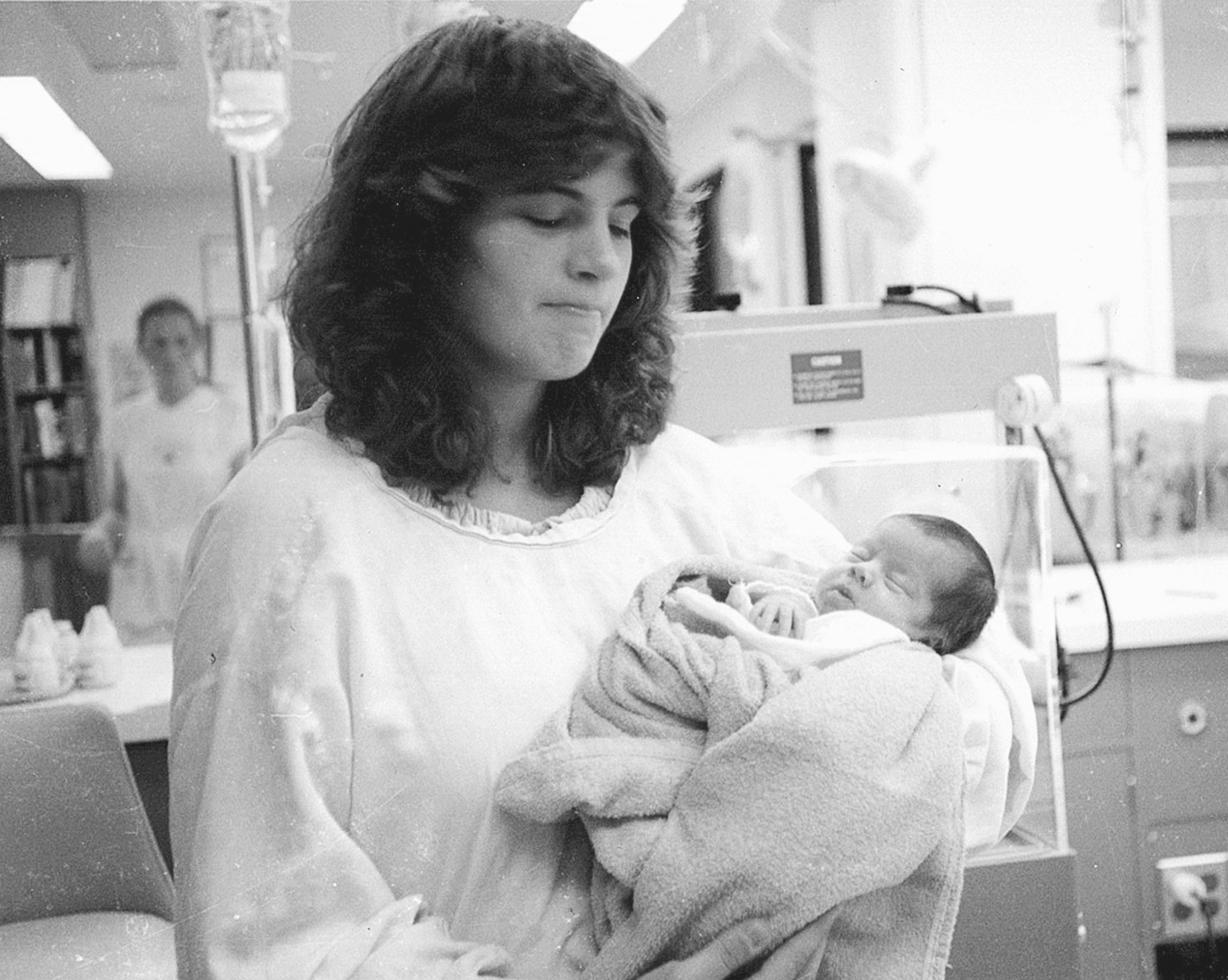

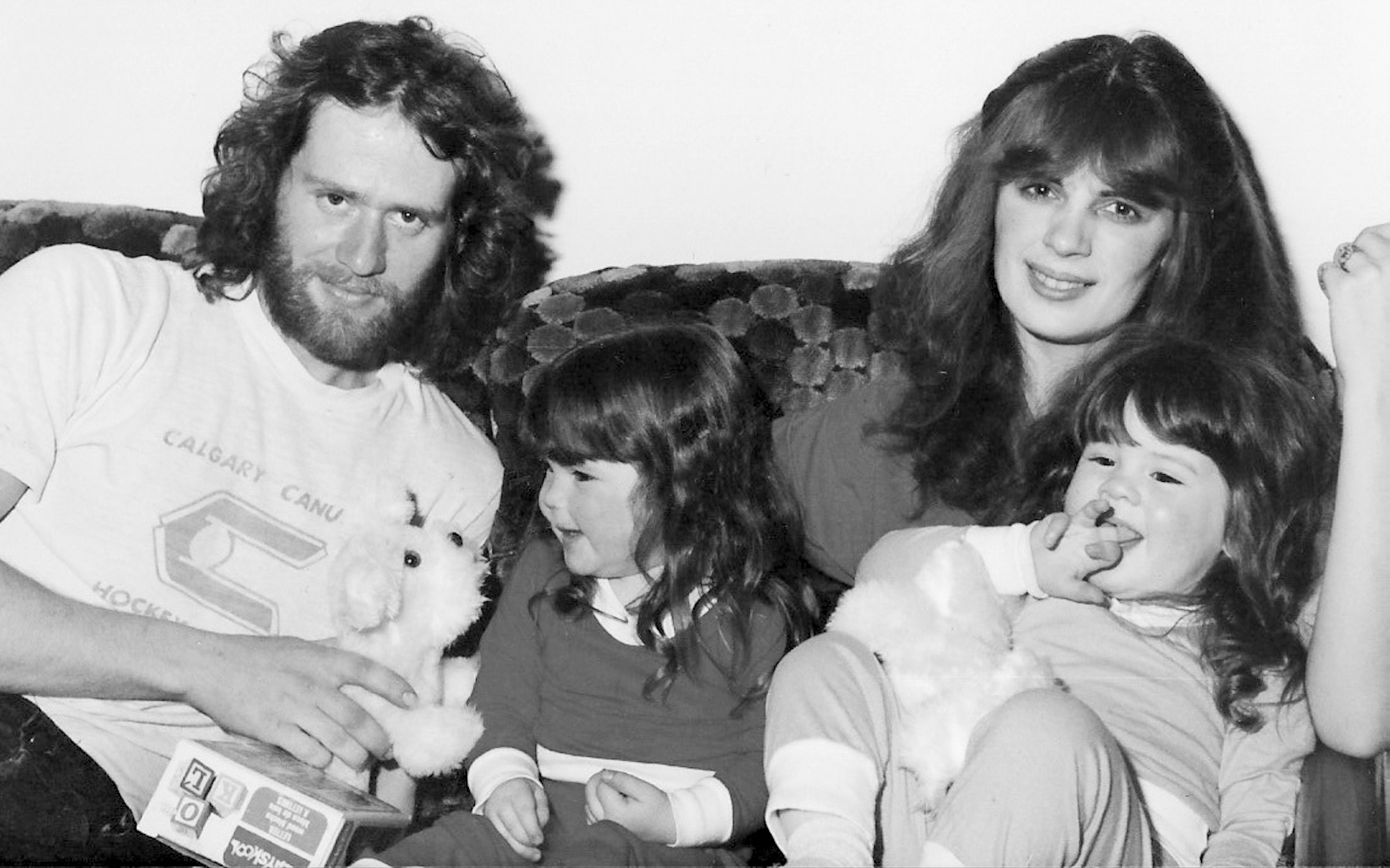

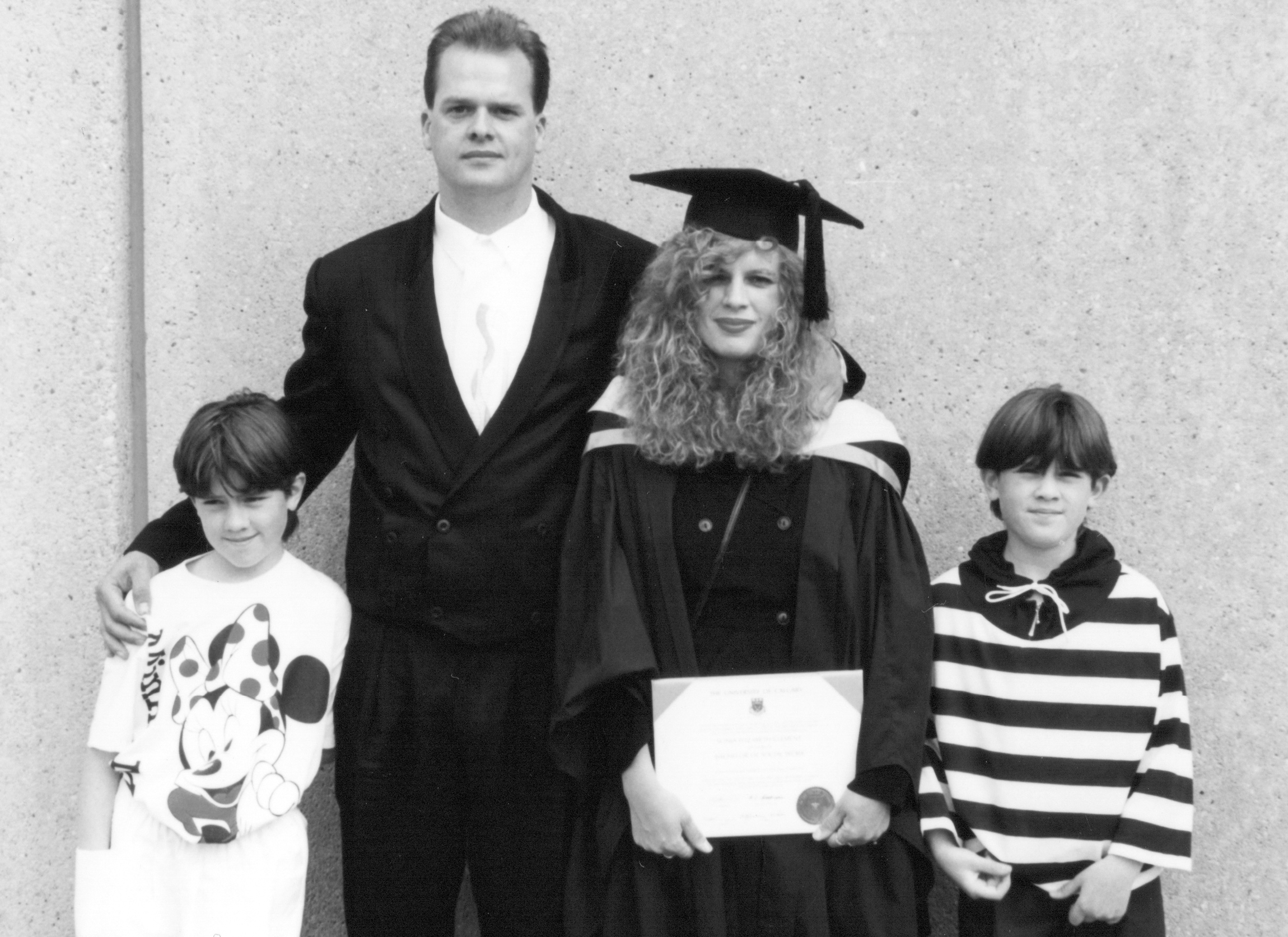

My twin sister, Tegan, and I were born at Calgary General Hospital on September 19, 1980. Our parents had met six years earlier at Saint Marys High School. Both arrived in Calgary under duress as teenagers: my father an orphan from Vancouver, and my mother fresh from Catholic boarding school in Saskatchewan. Our mother briefly dated our fathers brother, and our father dated our mothers best friend. After graduation, our father took a job working at a lumberyard, and our mother attended community college, where she earned a diploma in youth and child development. They began dating in the autumn of 1977 and married in June of 1978. With money for the down payment from our grandfather, they bought a house, and our mother became pregnant with twins. Thirty-two weeks later, we were prematurely born into the world eight minutes apart. Baby number one, born at 5:56 a.m., was my sister, Tegan Rain Quin. Baby number two was me, born at 6:04 a.m. and givenaccording to my mothers retellingher second-favorite name, Sara Keirsten Quin. When Tegan and I finally left the hospital a month later, we were still so tiny that our mother dressed us in dolls clothing.

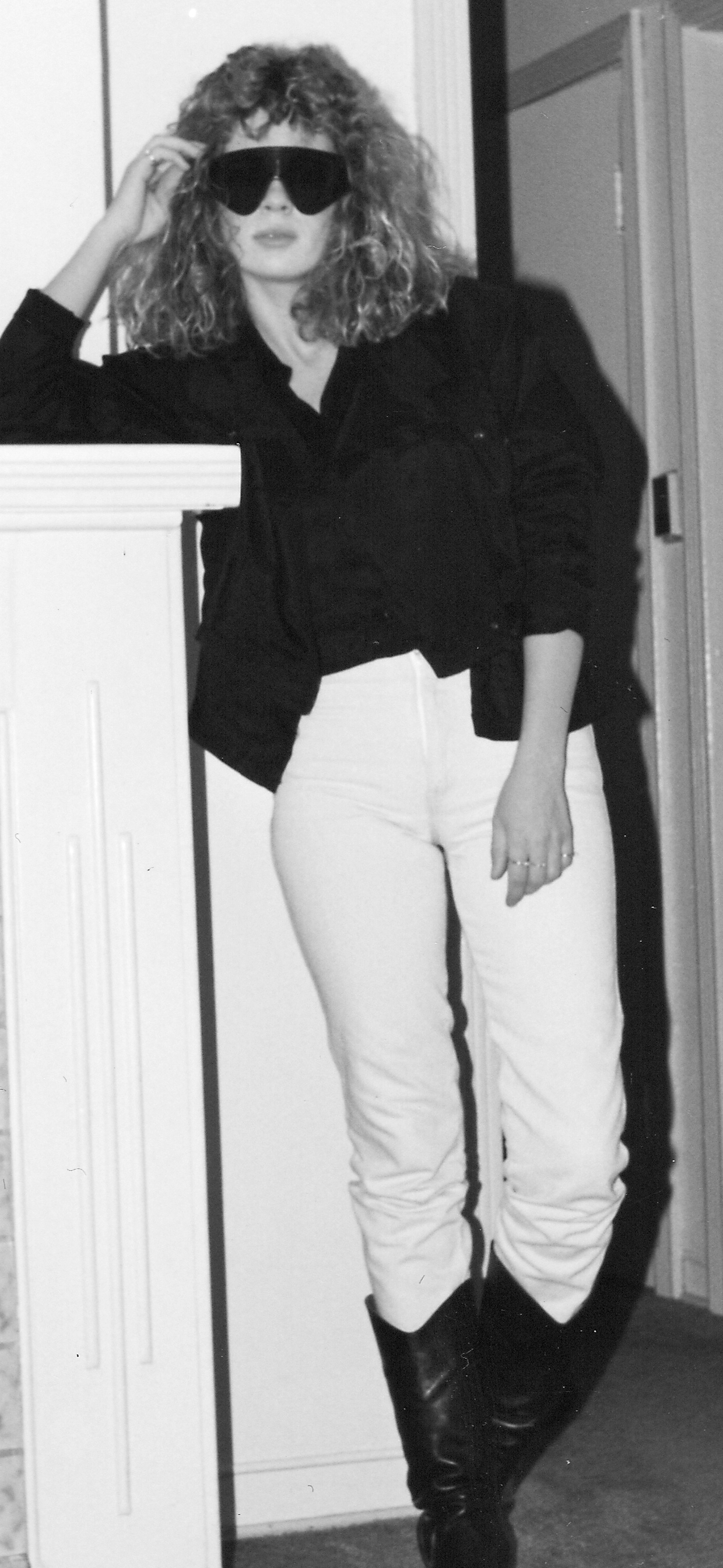

By all accounts we were extremely easy babies, soothed by the sight of each other, delighting in hand-to-hand combat for hours on a blanket spread out on the living room floor. Our parents marriage, however, was difficult. Our father often seemed depressed and prone to long silences that stretched for weeks; our mother was explosive and at her wits end. They separated in 1984, and our dad took off for Mexico. When he returned a few months later, he slept in one of a set of wooden bunk beds in the unfinished basement of our house, his alarm clock casting a hellish red glow. The summer before Tegan and I started grade one, he moved out for good and the divorce was finalized. In 1987 our mom started dating Bruce, a handsome man who worked at a steel mill and drove a Camaro. He moved in with us in 1990, and though he and our mother were not married, we referred to him as our stepdad.