The events in this memoir happened a long time ago and the people youll meet in these pages have all matured. We now all behave much more appropriately. Just in case that caveat is not enough, Ive changed several names to protect peoples privacy. Ive also recreated conversations and events to the best of my ability based on my elephantine memory, multiple boxes of letters, and passages from the angst-ridden journals Ive kept since I was eleven.

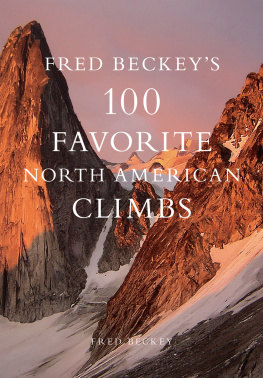

PROLOGUE: FIRST CLIMB

Load me up.

I stretched out my arms and my father passed me a liquor-store box marked Bacardi from the back of the station wagon. We were hauling our third load of gear a whole mile on foot to our cabin. Wed already dropped off sleeping bags, boxes of food, propane stoves, paint, tools and building materials. My little sister, Susan, and my mother had decided theyd had enough physical exertion for one day. Theyd stayed at the cabin to clean.

My parents, in cahoots with my two uncles, had recently bought a dilapidated little shack on Crown land in the Laurentians. Finally, theyd done something right. A cabin in the woods was my dream come true. Three years earlier, in 1972, wed moved from the Yukon to Ontario, and I still yearned for the snowy mountains, pink fireweed and wild rivers of the north. I was fourteen and counting down the years until I could escape, throw a pack on my back and hitch across Canada, all the way back to the Yukon to live off the land.

Drop this box and Ill have to thump you, my father said, then made a rumbly, Donald Ducklike noise in the back of his throat to show he was just joking. This noise signalled a good mood, something of a rarity with him since wed left the north.

As the weight settled into my arms I admired the bulge of my biceps. I was the only girl in gym class who could do the flexed-arm hang. My physical strength was one of the few things about me that impressed my father, though he had gone ballistic when I tried to show him I could do ten pull-ups on the shower curtain rod. On the drive here, hed promised I could help repair the siding and replace a few missing cedar shakes on the roof, saying I was handier with my hands than my mothers nincompoop brothers.

Dad threw a full pack on his back, scooped up a large plastic box, and we headed up the trail with me in the lead.

It was quiet in the woods. Just the sound of our feet shuffling through the leaves and pine needles, and the muffled clink, clink of the bottles in the box. The maple, beech and birch trees were just turning colour, crimson and gold against the deep green of the conifers. This was a real forest, so unlike the flat fields of hay and corn surrounding the bland, unincorporated town of Munster Hamlet, Ontario, where we now lived. The only wilderness I could find there was a scruffy clump of deciduous trees by the sewage lagoon where Id sit on my favourite boulder surrounded by bulrushes, composing restless poems and writing in my diary while trying to ignore the smell.

My uncles Steve and Dunk wound through the trees ahead carrying the cooler between them. I didnt want to catch up to them; it would break the spell of this special camaraderie I was feeling with my father. Moments like these were scarce. At home we walked on eggshells. Here in the Laurentians, I wanted to enjoy walking on a soft path of decaying maple leaves as long as I could. I wanted to enjoy my nice father.

I had two very distinct dads. The one here in the woods with me was my breakfast dad, who I could charm and joke around with. My after-work dad locked himself in his den with a bottle of Scotch after he got home every night. We had to stay the hell out of that ones way. Suppertime was so explosive that my big brother, Eric, no longer ate with us. My mother took his food down to his bedroom. On the rare occasion he and Dad found themselves in the same room, they ended up screaming obscenities, even shoving each other around. Eric had refused to come this weekend, saying hed rather have his toenails pulled out with pliers.

When we arrived at the cabin, I placed my load on the picnic table where my uncles were settling in beside the cooler. My father unshouldered his pack and leaned it against the table. He looked outdoorsy in his plaid shirt and the boots hed dusted off from his days of hiking the Chilkoot Trailjust like he did in his Arctic photos, looking out from the hood of a fur-lined parka with miles and miles of white spread out behind him. In the sixties, my father had worked as an Indian agent, living in Fort Chimo, Frobisher Bay and Inuvik, travelling to all the tiny Inuit outposts by dogsled and Ski-Doo. When I compared the old photos of him in the north to those of my mother sitting indoors on a government-issue sofa with a baby in one hand and a cigarette in the other, it was obvious who was having more fun. I wanted my fathers life, not the one my mother led, following her husband from community to community, popping out babies along the way, cleaning floors so cold they froze the mop. I intended to