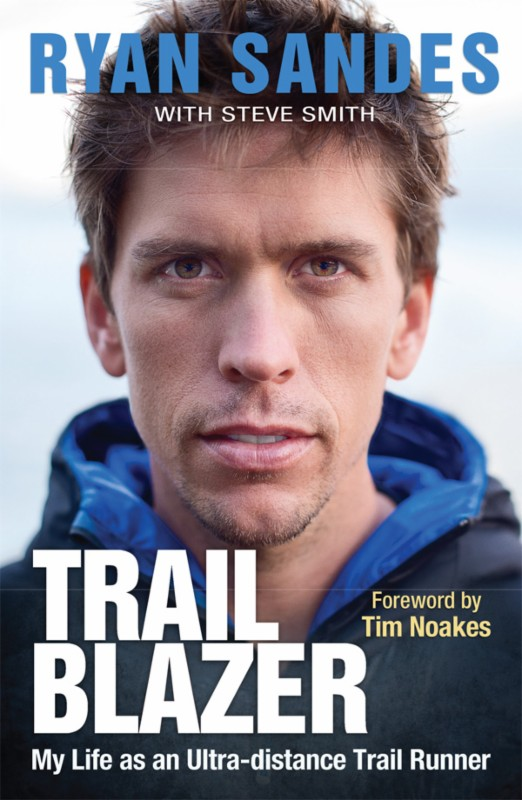

Published by Zebra Press

an imprint of Penguin Random House South Africa (Pty) Ltd

Reg. No. 1953/000441/07

The Estuaries No. 4, Oxbow Crescent, Century Avenue, Century City, 7441

PO Box 1144, Cape Town, 8000, South Africa

www.zebrapress.co.za

First published 2016

Publication Penguin Random House 2016

Text Ryan Sandes and Steve Smith 2016

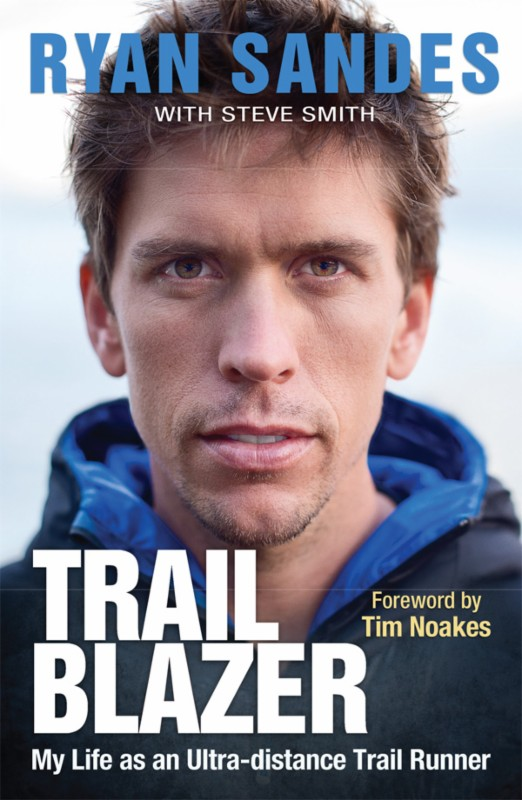

Cover photograph Craig Kolesky

Kelvin Trautman | Red Bull Content Pool (back cover)

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the copyright owners.

PUBLISHER: Marlene Fryer

MANAGING EDITOR: Janet Bartlet

EDITOR: Laetitia Sullivan

PROOFREADER: Mark Ronan

COVER AND TEXT DESIGNER: Ryan Africa

TYPESETTER: Monique van den Berg

Set in 11 pt on 15 pt Adobe Garamond

ISBN: 978 1 77022 905 1 (print)

ISBN: 978 1 77022 906 8 (ePub)

ISBN: 978 1 77022 907 5 (PDF)

CONTENTS

FOREWORD

However much we might think we know and understand, there are some phenomena which now, and perhaps forever, we will never fully comprehend. We call such happenings enigmas. Or even miracles. Ryan Sandes is one such.

You see, we know what leads to ultimate success as a world-class athlete. First you have to begin young and put in years of training. So you begin by running short distances a few kilometres at a time in training. And as you increase your training distances, so that after some months you can run for 30 minutes without stopping, you might consider entering a fun run of, say, five kilometres. If that goes well, and depending on your level of commitment and discipline, you might next consider running even further in training in order to enter a 10-kilometre race. And after many months, perhaps years, of running 10-kilometre races, you may be enticed to take the next big step up by entering a 21-kilometre race. For although a 21-kilometre race is just more than twice the 10-kilometre distance, to complete the added 11 kilometres takes at least three times the effort.

Then, after a year or more of adding 21-kilometre races to your repertoire, you are faced with the final challenge the one you could never have imagined when you began: the full 42-kilometre marathon the ultimate running Everest for the great majority of the worlds recreational runners.

Only in South Africa is the picture slightly different. For only here is there just one more rung on the ladder. Only here is the ultimate goal of the committed recreational runner an ultra-marathon like the 56-kilometre Two Oceans or the 88-kilometre Comrades Marathon. But even in South Africa, that is where the challenge ends for almost every marathoner 88 kilometres in a single day. And not one step further.

Having run enough of those races, I have often wondered why, like tens of thousands of other South African ultra-marathoners, I would never for a single moment consider running a race longer than the 88-kilometre Comrades Marathon.

Part of the reason (we must acknowledge) is that most of us are actors and we need an audience to inspire us. So its easy for us to run the Two Oceans and Comrades secure in the knowledge that millions will be watching our efforts either on the roadside or on national television. We thus see no reason to venture even one kilometre further. So a race of 100 to 160 kilometres? Utter madness.

Then what of a 250-kilometre, seven-day, six-stage race in which, for most of the way, we have only our own company? And, more importantly, only our own thoughts? And did you say the race would be on sand, in desert heat, or in extreme cold, or in the humidity and constant dangers of the Amazon jungle? Or perhaps at an altitude of two to three kilometres? Please are you crazy?

In this book, Ryan Sandes introduces us to the crazy. And his story raises questions that seriously challenge our comfortable understanding of what determines ultra-endurance performance and how you train to get there. For in his career Ryan has destroyed almost all of our preconceptions of what it takes to become a world-class ultra-distance runner. And if we cannot explain why and how he has achieved what he has, can we scientists really claim to properly understand what we profess as our indisputable truths?

So here are the bare facts that demand our understanding and explanation.

Ryans dad is a South African ultra-marathon runner, a veteran of the 56-kilometre Two Oceans Marathon. Ryan grows up with little interest in running; in fact, he describes himself as a party person. Then, in June 2006, friends with whom he has shared a few short runs enter a local 21-kilometre half-marathon. Since Ryans dad is a marathoner, Ryan enters the full marathon. In training he manages a single run of 19 kilometres, during which he is reduced to walking on numerous occasions. Undeterred, he runs the marathon keeping pace with the lead woman for 30 kilometres before fading to finish in 3:28:45. He decides he will break the three-hour barrier in his next marathon, a feat his father never achieved.

Training a bit harder, he runs his next marathon in early 2007, finishing in 3:08. A few months later, he lowers his marathon time to 3:01. He begins to train more regularly and starts to run in trail races, in which he finishes closer to the winners.

In October 2007, he sends off his entry form for the 250-kilometre, seven-day, six-stage Gobi March, to be held in June 2008. More experienced runners point out that this is a 250-kilometre race, that the furthest distance he has ever run in his life is 42 kilometres, and that these races are fully self-supported, meaning that from the start he must carry all he will need for the entire race.

Undeterred, he begins to train intensively with coach Ian Waddell. The first stage of the Gobi March is 40 kilometres. He begins conservatively and has no idea how he is running. With eight kilometres to go, he is informed that he is in second place. He speeds up and wins the stage. He is overcome by emotion. He wins all the next four stages, and the overall race, by 31 minutes. Inspired by his success and realising that he has some ability for this type of event, he enters the 2008 250-kilometre, seven-day, six-stage Sahara Race in Egypt. He again wins all five stages.

In 2009 he places second a few minutes behind the winner in the 250-kilometre, seven-day, six-stage Namibia (Sahara) Desert Race and wins the 2009 242- kilometre, seven-day, six-stage Jungle Marathon in the Amazon. CNN rates this race as the worlds toughest endurance race. It includes temperatures of 40 C, humidity of 98 per cent, a high jungle canopy that admits no direct sunlight, swamps with anacondas, and river crossings with piranhas and caimans as companions.

In 2010 he wins two more 250-kilometre, seven-day, six-stage races in the 4 Deserts Series the Atacama Challenge in Chile and the Last Desert Race in Antarctica. As a result, by the end of 2010 he is the only competitor to have won every stage of each of the four desert races. In 2011 he wins the 250-kilometre, seven-day, six-stage Racing the Planet in Nepal by more than two-and-a-half hours. The race reaches a peak altitude of 3 200 metres (10 500 feet) and involves total elevation gains of 9 000 metres and descents of 9 700 metres.

Having conquered the seven-day races, he decides to tackle the worlds most famous single-day ultra-marathon trail races. In 2011 he wins the Leadville 100 Mile Trail Run at high altitude in the third-fastest time in history. In 2012 he wins the Vibram Hong Kong 100-kilometre ultra in a new record time. He adds the North Face 100-kilometre in Australia and, at his first attempt, finishes second in the second-fastest time in history in perhaps the most famous of all trail races the Western States 100 Miler USA. He concludes the year by setting a new fastest known time of 6 hours 57 minutes for the Fish River canyon traverse.

Next page