GODDESS OF THE MARKET

GODDESS OF THE MARKET

Ayn Rand and the American Right

Jennifer Burns

OXFORD

UNIVERSITY PRESS

Oxford University Press Oxford University Press, Inc., publishes works that further Oxford Universitys objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education.

Oxford New York

Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi

Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi

New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto

With offices in

Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece

Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore

South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam

Copyright 2009 by Oxford University Press, Inc.

Published by Oxford University Press, Inc.

198 Madison Avenue, New York, New York 10016

www.oup.com

Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Oxford University Press.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Burns, Jennifer, 1975

Goddess of the market : Ayn Rand and the American Right / Jennifer Burns.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-19-532487-7

1. Rand, Ayn. 2. Rand, AynPolitical and social views.

3. Rand, AynCriticism and interpretation. 4. Novelists, American20th

centuryBiography. 5. Women novelists, AmericanBiography.

6. PhilosophersUnited StatesBiography.

7. Political cultureUnited StatesHistory20th century.

8. Right and left (Political science)History20th century.

9. United StatesPolitics and government19451989. I. Title.

PS 3535.A547Z587 2009

813.52dc22 2009010763

1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2

Printed in the United States of America

on acid-free paper

TO MY FATHER

CONTENTS

GODDESS OF THE MARKET

HER EYES WERE what everyone noticed first. Dark and widely set, they dominated her plain, square face. Her glare would wilt a cactus, declared Newsweek magazine, but to Ayn Rands admirers, her eyes projected clairvoyance, insight, profundity. When she looked into my eyes, she looked into my soul, and I felt she saw me, remembered one acquaintance. Readers of her books had the same feeling. Rands words could penetrate to the core, stirring secret selves and masked dreams. A graduate student in psychology told her, Your novels have had a profound influence on my life. It was like being reborn.... What was really amazing is that I dont remember ever having read a book from cover to cover. Now, Im just the opposite. Im always reading. I cant seem to get enough knowledge. Sometimes Rand provoked an adverse reaction. The libertarian theorist Roy Childs was so disturbed by The Fountainheads atheism that he burned the book after finishing it. Childs soon reconsidered and became a serious student and vigorous critic of Rand. Her works launched him, as they did so many others, on an intellectual journey that lasted a lifetime.

Although Rand celebrated the life of the mind, her harshest critics were intellectuals, members of the social class into which she placed herself. Rand was a favorite target of prominent writers and critics on both the left and the right, drawing fire from Sidney Hook, Whittaker Chambers, Susan Brownmiller, and William F. Buckley Jr. She gave as good as she got, calling her fellow intellectuals frightened zombies and witch doctors. Ideas were the only thing that truly mattered, she believed, both in a persons life and in the course of history. What are your premises? was her favorite opening question when she met someone new.

Today, more than twenty years after her death, Rand remains shrouded in both controversy and myth. The sales of her books are A host of advocacy organizations promote her work, and rumors swirl about a major motion picture based on Atlas Shrugged. The blogosphere hums with acrimonious debate about her novels and philosophy. In many ways, Rand is a more active presence in American culture now than she was during her lifetime.

Because of this very longevity, Rand has become detached from her historical context. Along with her most avid fans, she saw herself as a genius who transcended time. Like her creation Howard Roark, Rand believed, I inherit nothing. I stand at the end of no tradition. I may, perhaps, stand at the beginning of one. She made grandiose claims for Objectivism, her fully integrated philosophical system, telling the journalist Mike Wallace, If anyone can pick a rational flaw in my philosophy, I will be delighted to acknowledge him and I will learn something from him. Until then, Rand asserted, she was the most creative thinker alive. The only philosopher she acknowledged as an influence was Aristotle. Beyond his works, Rand insisted that she was unaffected by external influences or ideas. According to Rand and her latter-day followers, Objectivism sprang, Athena-like, fully formed from the brow of its creator.

Commentary on Rand has done little to dispel this impression. Because of her extreme political views and the nearly universal consensus among literary critics that she is a bad writer, few who are not committed Objectivists have taken Rand seriously. Unlike other novelists of her stature, until now Rand has not been the subject of a full-length biography. Her life and work have been described instead by her former friends, enemies, and students. Despite her emphasis on integration, most of the books published about Rand have been essay collections rather than large-scale works that develop a sustained interpretation of her importance.

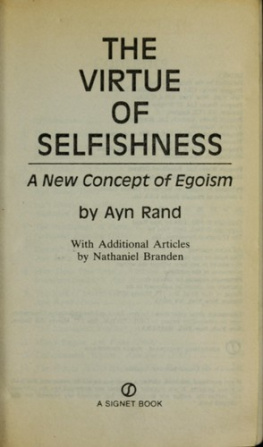

This book firmly locates Rand within the tumultuous American century that her life spanned. Rands defense of individualism, celebration of capitalism, and controversial morality of selfishness can be understood only against the backdrop of her historical moment. All sprang from her early life experiences in Communist Russia and became the most powerful and deeply enduring of her messages. What Rand confronted in her work was a basic human dilemma: the failure of good intentions. Her indictment of altruism, social welfare, and service to others sprang from her belief that these ideals underlay Communism, Nazism, and the wars that wracked the century. Rands solution, characteristically, was extreme: to eliminate all virtues that could possibly be used in the service of totalitarianism. It was also simplistic. If Rands great strength as a thinker was to grasp interrelated underlying principles and weave them into an impenetrable logical edifice, it was also her great weakness. In her effort to find a unifying cause for all the trauma and bloodshed of the twentieth century, Rand was attempting the impossible. But it was this deadly serious quest that animated all of her writing. Rand was among the first to identify the problem of the modern states often terrifying power and make it an issue of popular concern.

She was also one of the first American writers to celebrate the creative possibilities of modern capitalism and to emphasize the economic value of independent thought. In a time when leading intellectuals assumed that large corporations would continue to dominate economic life, shaping their employees into soulless organization men, Rand clung to the vision of the independent entrepreneur. Though it seemed anachronistic at first, her vision has resonated with the knowledge workers of the new economy, who see themselves as strategic operators in a constantly changing economic landscape. Rand has earned the unending devotion of capitalists large and small by treating business as an honorable calling that can engage the deepest capacities of the human spirit.

Next page