ALSO BY OLIVER SACKS

Migraine

Awakenings

A Leg to Stand On

The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat

Seeing Voices

An Anthropologist on Mars

The Island of the Colorblind

Uncle Tungsten

Oaxaca Journal

Musicophilia

The Minds Eye

Hallucinations

On the Move

This Is a Borzoi Book

Published by Alfred A. Knopf and Alfred A. Knopf Canada

Copyright 2015 by the Estate of Oliver Sacks

Foreword copyright 2015 Kate Edgar and Bill Hayes

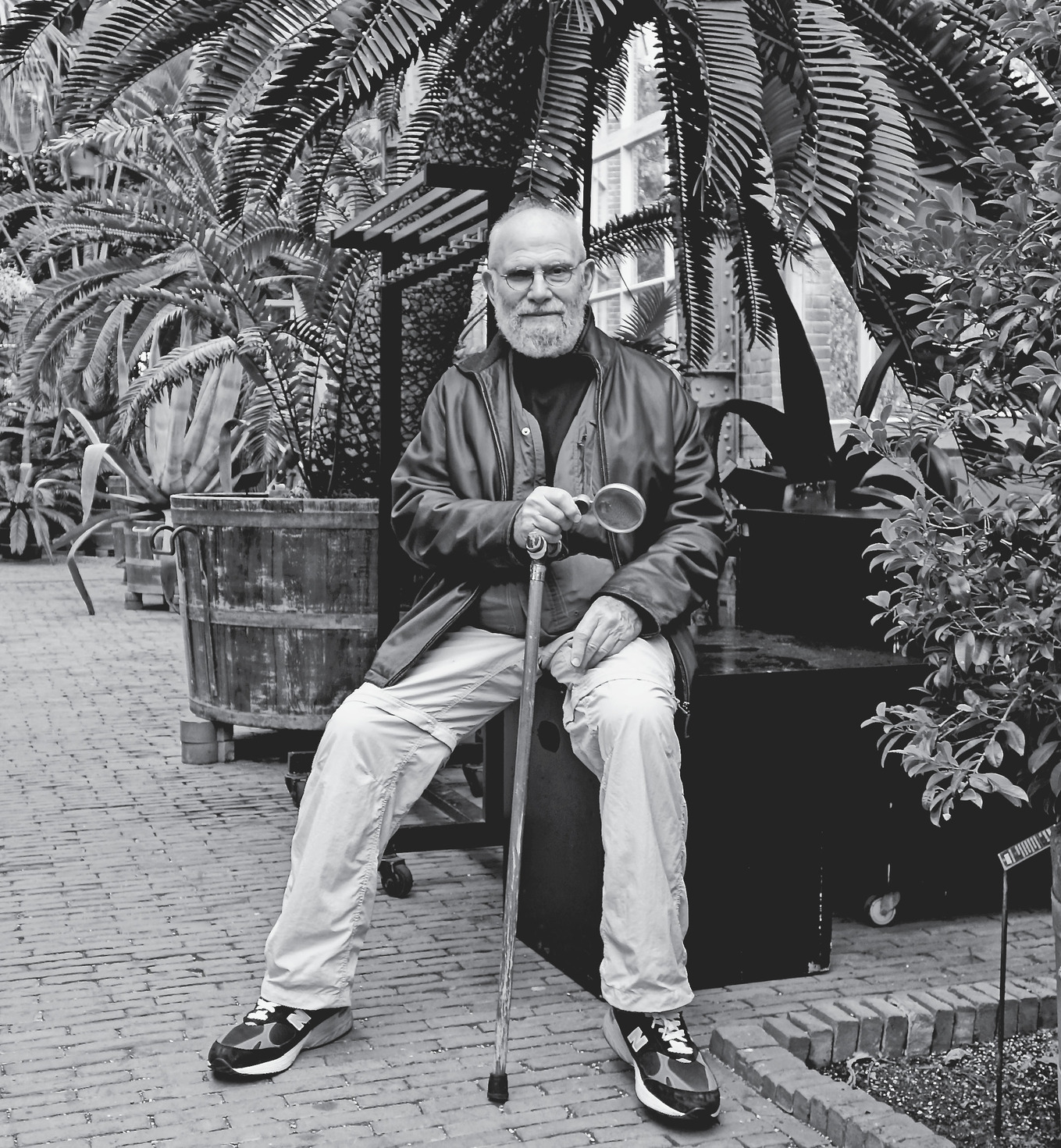

Photographs copyright 2015 by Bill Hayes

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Random House LLC, New York, and in Canada by Alfred A. Knopf of Canada, a division of Penguin Random House Canada Ltd., Toronto.

www.aaknopf.com

www.penguinrandomhouse.ca

www.oliversacks.com

Knopf, Borzoi Books, and the colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC. Knopf Canada and colophon are trademarks of Penguin Random House Canada Ltd.

ISBN (USA) 9780451492937 (hardcover); 9780451492968 (eBook)

ISBN (Canada) 9780345811363 (hardcover); 9780345811370 (eBook)

Library of Congress Control Number: 2015952928

These pieces originally appeared in The New York Times as follows: Mercury as The Joy of Old Age (July 6, 2013), My Own Life (February 19, 2015), My Periodic Table (July 24, 2015), and Sabbath (August 14, 2015).

Special thanks to Peter Catapano

Cover design by Carol Devine Carson

v4.1_r1

ep

I am now face to face with dying, but I am not finished with living.

Contents

Foreword

I N THIS QUARTET OF ESSAYS, written in the last two years of his life, Oliver Sacks faces aging, illness, and death with remarkable grace and clarity. The first essay, Mercury, written in one sitting just days before his eightieth birthday in July 2013, celebrates the pleasures of old agewithout dismissing the frailties of body and mind that may come with it.

Eighteen months later, shortly after completing a final draft of his memoir On the Move, Dr. Sacks learned that the rare form of melanoma in his eye, first diagnosed in 2005, had metastasized to his liver. There were very few treatment options for this particular type of cancer, and his physicians prognosticated that he might have as little as six months to live. Within days he had completed the essay My Own Life, in which he expressed his overwhelming feeling of appreciation for a life well lived. And yet he hesitated to publish this immediately: Was it premature? Did he want to go public with the news of his terminal illness? A month later, literally as he entered surgery for a treatment that would give him several extra months of active life, he asked to have the essay sent to The New York Times, where it was published the next day. The enormous and sympathetic reaction to My Own Life was immensely gratifying to him.

In May, June, and early July of 2015, he enjoyed relative good healthwriting, swimming, playing piano, and traveling. He wrote several essays during this period, including My Periodic Table, in which he reflects on his lifelong love for the periodic table of the elements and on his own mortality.

By August, Dr. Sacks health was declining rapidly, but he devoted his last energies to writing. The final piece in this book, Sabbath, was particularly important to him, and he went over every word of the essay time and again, distilling it to its essence. It was published two weeks before his death on August 30, 2015.

Kate Edgar and Bill Hayes

Mercury

L AST NIGHT I DREAMED about mercuryhuge, shining globules of quicksilver rising and falling. Mercury is element number 80, and my dream is a reminder that on Tuesday, I will be eighty myself.

Elements and birthdays have been intertwined for me since boyhood, when I learned about atomic numbers. At eleven, I could say I am sodium (element 11), and now at seventy-nine, I am gold. A few years ago, when I gave a friend a bottle of mercury for his eightieth birthdaya special bottle that could neither leak nor breakhe gave me a peculiar look, but later sent me a charming letter in which he joked, I take a little every morning for my health.

Eighty! I can hardly believe it. I often feel that life is about to begin, only to realize it is almost over. My mother was the sixteenth of eighteen children; I was the youngest of her four sons, and almost the youngest of the vast cousinhood on her side of the family. I was always the youngest boy in my class at high school. I have retained this feeling of being the youngest, even though now I am almost the oldest person I know.

I thought I would die at forty-one, when I had a bad fall and broke a leg while mountaineering alone. I splinted the leg as best I could and started to lever myself down the mountain, clumsily, with my arms. In the long hours that followed, I was assailed by memories, both good and bad. Most were in a mode of gratitudegratitude for what I had been given by others, gratitude too that I had been able to give something back. Awakenings, my second book, had been published the previous year.

At nearly eighty, with a scattering of medical and surgical problems, none disabling, I feel glad to be aliveIm glad Im not dead! sometimes bursts out of me when the weather is perfect. (This is in contrast to a story I heard from a friend who, walking with Samuel Beckett in Paris on a perfect spring morning, said to him, Doesnt a day like this make you glad to be alive? to which Beckett answered, I wouldnt go as far as that.) I am grateful that I have experienced many thingssome wonderful, some horribleand that I have been able to write a dozen books, to receive innumerable letters from friends, colleagues, and readers, and to enjoy what Nathaniel Hawthorne called an intercourse with the world.

I am sorry I have wasted (and still waste) so much time; I am sorry to be as agonizingly shy at eighty as I was at twenty; I am sorry that I speak no languages but my mother tongue and that I have not traveled or experienced other cultures as widely as I should have done.