Dr. Oliver Sacks spent more than fifty years working as a neurologist and writing books about the neurological predicaments and conditions of his patients, including The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat, Musicophilia, and Awakenings. The New York Times referred to him as the poet laureate of medicine, and over the years, he received many awards, including honors from the Guggenheim Foundation, the National Science Foundation, the American Academy of Arts and Letters, the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, and the Royal College of Physicians. His memoir On the Move was published shortly before his death in August 2015.

ALSO BY OLIVER SACKS

Migraine

Awakenings

The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat

Seeing Voices

An Anthropologist on Mars

The Island of the Colorblind

Uncle Tungsten

Oaxaca Journal

Musicophilia

The Minds Eye

Hallucinations

On the Move

Gratitude

The River of Consciousness

Everything in Its Place

FIRST VINTAGE BOOKS EDITION, SEPTEMBER 2020

Copyright 1984 by Oliver Sacks

Afterword copyright 1993 by Oliver Sacks

Foreword copyright 2020 by Kate Edgar

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Vintage Books, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York. Originally published in hardcover in the United States by Summit Books, a division of Simon & Schuster, Inc., New York, in 1984, and subsequently published by HarperPerennial, a division of HarperCollins Publishers, New York, in 1993.

Vintage and colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

The Library of Congress has cataloged the Summit Books edition as follows:

Name: Sacks, Oliver, 19332015.

Title: A leg to stand on / Oliver Sacks.

Description: New York : Summit Books, c1984.

Identifier: LCCN 84008497

Subjects: LCSH : Sacks, Oliver, 19332015. | NeurologistsEnglandBiography. | People with disabilitiesEnglandBiography.

Classification: LCC RC 339.52. S 23 A 35 1984 | DDC 362.4/3/0924 B

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/84008497

Vintage Books Trade Paperback ISBN9780593311004

Ebook ISBN9780593311011

Cover design by Linda Huang

Cover illustration: leg Aaltazar/Getty Images

www.vintagebooks.com

ep_prh_5.6.0_c0_r0

To the memory of A. R. Luria

Contents

Foreword

by Kate Edgar

When I first began working with Oliver Sacks, in 1982, it was to help him put the finishing touches on the Leg book, as he often called it. I was a young editor, freelancing, and his publisher had sent me a manuscript for part of the book. It was covered with crossings-out and densely packed handwriting which was nearly indecipherable. On top of that, the pages were sometimes blotchy, as if they had been caught in the rain. It was not until I got to know Oliver better that I found out why. He adored swimming, he told me, and on summer weekends, he often rented a tiny room near a lake in the Catskills. Swimming helped him shape the flow of ideas, and he would keep a pen and a sheaf of paper by the edge of the lake so that, if a paragraph suddenly came to him while he was in the water, he could rush out, dripping, to write it down.

Oliver, clearly, was unlike anyone I had ever met, in many ways, and this book was my immersion into his world.

With his first two books, Migraine and Awakenings, he had begun to develop what he called case histories, or clinical tales. Deeply influenced by the nineteenth-century neurologists (whom he talked about and quoted almost as if they were personal friends), his case histories were novelistically rich, compassionate, and not without a sympathetic humor. These portraits were profoundly insightful and humane, never losing sight of the person, the individual, behind the syndrome.

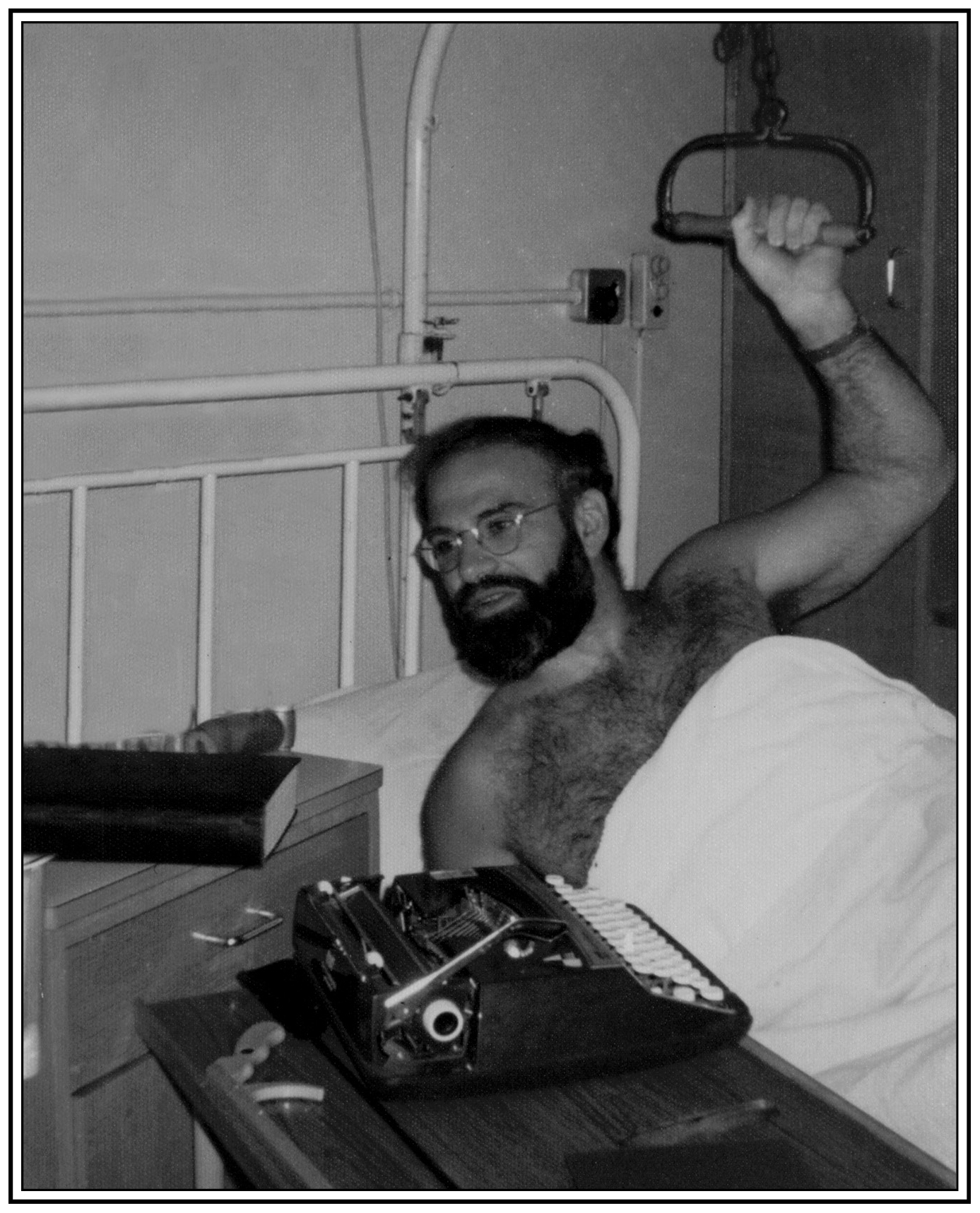

A Leg to Stand On, his third book, is also a case history, but his own case history, following a serious injury which nearly cost him his life. Here he meditates on the meaning of illness and recovery, and on the complexities of the doctor-patient relationship. He, the physician, is now the patient, and he chronicles this in exquisitely evocative, intimate, moment-by-moment detailincluding the frustration and sometimes despair of not being believed by his own doctors.

Much more than any of his other books, perhaps, Leg reveals Oliver as a poet and philosopher, no less than a physician. He invokes philosophers from Arendt and Nietzsche to Kant to interrogate the existential problems of nothingness, and one can feel, too, how deeply he has imbibed the poetry of John Donne, T. S. Eliot, and the Psalms. The language he uses in Leg is lush, sometimes eccentric, but always highly original. Like Sir Thomas Browne, he pushes the English language to its extreme, drawing upon obscure words, or making up his own phrases when he needs to (kipperish euphoria, for instance, to describe the aftermath of a particularly delectable breakfast). He loves to play with repetitions and permutations; one can almost hear the OED entries echoing in his mind. Sometimes he calls upon a soaring, rhythmic poetry that almost demands to be put into stanzas, like this opening sentence of the Quickening chapter:

Throughout these twelve, endless yet empty days the leg itself had not changed a jot; it remained entirely motionless, toneless, senseless, beneath its white sepulchre of chalk.

His rendering of scenes and dialogue in the hospital is often wryly comic, bringing to mind other literary heroes of his, like Dickens, Chekhov, or Conan Doyle. He even slips in a little reference to his beloved Star Trek, by naming one of the nurses after George Takeis character, Sulu.

Olivers fondness for Star Trek went hand in hand with his love of H. G. Wells and many other science fiction writers, as well as his admiration for the travel narratives of the great nineteenth-century explorers and naturalists like Darwin, Humboldt, and Wallace. He felt that the best neurologists, too, were natural historians and describers, and, in the chapter called Limbo, he writes:

I had explored many strange, neuropsychological landsthe furthest Arctics and Tropics of neurological disorder. But now I decidedor was I forced?to explore a chartless land. The land which faced me was No-land, Nowhere.

Exploring this abyss of nothingness and the travails of patienthood, and eventually returning to health and understanding, Oliver emerges newly grounded, more deeply comprehending of his own patients. This is evident in the essays that came together in The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hatessays that he had begun to publish during the years in which he was writing A Leg to Stand On. As he writes in the final chapter, Understanding,

I could now open myself fully to the experiences of my patients, enter imaginatively into their experiences and be accessible and hospitable in these regions of dread. I would listen to patients as never beforeto their stammered half-articulate communications as they journeyed through a region I knew so well myself.