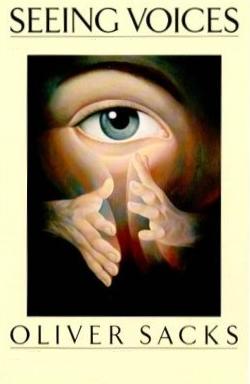

Oliver Sacks

Seeing Voices

A Journey into the World of the Deaf

1989

Written by the author of The Man Who Mistook his Wife for a Hat, this book begins with the history of deaf people in the 18th century, the often outrageous ways in which they have been treated in the past, and their continuing struggle for acceptance in a hearing world. And it examines the visual language of the deafSignwhich has only in the past decade been recognized fully as a language linguistically complete, rich, and as expressive as any spoken language. Oliver Sacks has also written Migraine, Awakenings and A Leg to Stand on.

INTRO

[Sign language] is, in the hands of its masters, a most beautiful and expressive language, for which, in their intercourse with each other and as a means of easily and quickly reaching the minds of the deaf, neither nature nor art has given them a satisfactory substitute.

It is impossible for those who do not understand it to comprehend its possibilities with the deaf, its powerful influence on the moral and social happiness of those deprived of hearing, and its wonderful power of carrying thought to intellects which would otherwise be in perpetual darkness. Nor can they appreciate the hold it has upon the deaf. So long as there are two deaf people upon the face of the earth and they get together, so long will signs be in use.

J. Schuyler Long Head teacher, Iowa School for the Deaf.

The Sign Language (1910)

Strobe photograph of ASL signs join and inform. (Reprinted by permission from The Signs of Language, E.S. Klima & U. Bellugi. Harvard University Press, 1979.).

PREFACE

T hree years ago I knew nothing of the situation of the deaf, and never imagined that it could cast light on so many realms, above all, on the realm of language. I was astonished to learn about the history of deaf people, and the extraordinary (linguistic) challenges they face, astonished too to learn of a completely visual language, Sign, a language different in mode from my own language, Speech. It is all too easy to take language, ones own language, for grantedone may need to encounter another language, or rather another mode of language, in order to be astonished, to be pushed into wonder, again. When I first read of the deaf and their singular mode of language, Sign, I was incited to embark on an exploration, a journey. This journey took me to deaf people and their families; to schools for the deaf, and to Gallaudet, the unique university of the deaf; it took me to Marthas Vineyard, where there used to exist a hereditary deafness and where everybody (hearing no less than deaf) spoke Sign; it took me to towns like Fremont and Rochester, where there is a remarkable interface of deaf and hearing communities; it took me to the great researchers on Sign, and the conditions of the deafbrilliant and dedicated researchers who communicated to me their excitement, their sense of unexplored regions and new frontiers.

1. Although the term Sign is usually used to denote American Sign Language (ASL), I use it in this book to refer to all indigenous signed languages, past and present (e.g., American Sign Language, French Sign, Chinese Sign, Yiddish Sign, and Old Kentish Sign). But it excludes signed forms of spoken languages (e.g., Signed English), which are mere transliterations and lack the structure of genuine sign languages.

My journey has taken me to look at language, at the nature of talking and teaching, at child development, at the development and functioning of the nervous system, at the formation of communities, worlds, and cultures, in a way which was wholly new to me, and which has been an education and a delight. It has, above all, afforded a completely new perspective on age-old problems, a new and unexpected view onto language, biology, and cultureit has made the familiar strange, and the strange familiar.

My travels left me both enthralled and appalled. I was appalled as I discovered how many of the deaf never acquire the powers of good languageor thinkingand how poor a life might lie in store for them.

But almost at once I was to be made aware of another dimension, another world of considerations, not biological, but cultural. Many of the deaf people I met had not merely acquired good language, but language of an entirely different sort, a language that served not only the powers of thought (and indeed allowed thought and perception of a kind not wholly imaginable by the hearing), but served as the medium of a rich community and culture. Whilst I never forgot the medical status of the deaf, I had now to see them in a new, ethnic light, as a people, with a distinctive language, sensibility, and culture of their own.

2. Some in the deaf community mark this distinction by a convention whereby audiological deafness is spelled with a small d, to distinguish it from Deafness with a big d, as a linguistic and cultural entity.

It might be thought that the story and study of deaf people, and their language, is something of extremely limited interest. But this, I believe, is by no means the case. It is true that the congenitally deaf only constitute about 0.1 percent of the population, but the considerations that arise from them raise issues of the widest and deepest importance. The study of the deaf shows us that much of what is distinctively human in usour capacities for language, for thought, for communication, and culturedo not develop automatically in us, are not just biological functions, but are, equally, social and historical in origin; that they are a giftthe most wonderful of giftsfrom one generation to another. We see that Culture is as crucial as Nature.

The existence of a visual language, Sign, and of the striking enhancements of perception and visual intelligence that go with its acquisition, shows us that the brain is rich in potentials we would scarcely have guessed of, shows us the almost unlimited plasticity and resource of the nervous system, the human organism, when it is faced with the new and must adapt. If this subject shows us the vulnerabilities, the ways in which (often unwittingly) we may harm ourselves, it shows us, equally, our unknown and unexpected strengths, the infinite resources for survival and transcendence which Nature and Culture, together, have given us. Thus, although I hope that deaf people, and their families, teachers, and friends, may find this book of special interest, I hope that the general reader may turn to it, too, for an unexpected perspective on the human condition.

This book is in three parts. The first was written in 1985 and 1986, and started as a review of a book on the history of the deaf, Harlan Lanes When the Mind Hears. This had expanded to an essay by the time it was published (in the New York Review of Books, March 27, 1986), and has since been further enlarged and revised. I have, however, left certain formulations and locutions, with which I no longer fully agree, in place, because I felt I should preserve the original, whatever its defects, as reflecting the way I first thought about the subject. Part III was stimulated by the revolt of the students at Gallaudet in March 1988, and was published in the New York Review of Books on June 2, 1988. This too has been considerably revised and enlarged for the present book. Part II was written last, in the fall of 1988, but is, in some ways, the heart of the bookat least the most systematic, but also the most personal, view of the whole subject. I should add that I have never found it possible to tell a story, or pursue a line of thought, without taking innumerable side trips or excursions along the way, and finding my journey the richer for this.