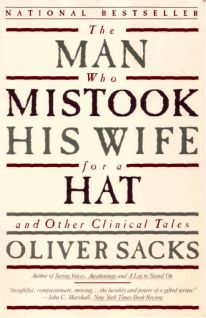

The man who mistook his wife for a hat

OLIVER SACKS

Who

MISTOOK

HIS WIFE

for

a HAT

and other clinical tales

To Leonard Shengold, M.D.

THE MAN WHO MISTOOK HIS WIFE FOR A HAT AND OTHER CLINICAL TALESCopyright 1970,

1981, 1983, 1984, 1985 by Oliver Sacks. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For information address HarperCollins Publishers, 10 East 53rd Street, New York, NY 10022.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Sacks, Oliver W.

The man who mistook his wife for a hat and other clinical tales.

Bibliography: p.

1. Neurology-Anecdotes, facetiae, satire, etc. I. Title.

[RC351.S195 1987] 616.8 86-45686

ISBN 0-06-097079-0 (pbk.)

Contents

Preface page vii

Part One - LOSSES Introduction page 3

1 The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat page 8

2 The Lost Mariner page 23

3 The Disembodied Lady page 43

4 The Man Who Fell out of Bed page 55

5 Hands page 59

6 Phantoms page 66

7 On the Level page 71

8 Eyes Right! page 77

9 The President's Speech page 80

Part Two - EXCESSES Introduction page 87

10 Witty Ticcy Ray page 92

11 Cupid's Disease page 102

12 A Matter of Identity page 108

13 Yes, Father-Sister page 116

14 The Possessed page 120

Part Three - TRANSPORTS Introduction page 129

15 Reminiscence page 132

16 Incontinent Nostalgia page 150

17 A Passage to India page 153

18 The Dog Beneath the Skin page 156

19 Murder page 161

20 The Visions of Hildegard page 166

Part Four - THE WORLD OF THE SIMPLE

Introduction page 173

21 Rebecca page 178

22 A Walking Grove page 187

23 The Twins page 195

24 The Autist Artist page 214

Bibliography page 234

Preface

The last thing one settles in writing a book,' Pascal observes, 'is what one should put in first.' So, having written, collected and arranged these strange tales, having selected a title and two epigraphs, I must now examine what I have done-and why.

The doubleness of the epigraphs, and the contrast between them-indeed, the contrast which Ivy McKenzie draws between the physician and the naturalist-corresponds to a certain doubleness in me: that I feel myself a naturalist and a physician both; and that I am equally interested in diseases and people; perhaps, too, that I am equally, if inadequately, a theorist and dramatist, am equally drawn to the scientific and the romantic, and continually see both in the human condition, not least in that quintessential human condition of sickness-animals get diseases, but only man falls radically into sickness.

My work, my life, is all with the sick-but the sick and their sickness drives me to thoughts which, perhaps, I might otherwise not have. So much so that I am compelled to ask, with Nietzsche: 'As for sickness: are we not almost tempted to ask whether we could get along without it?'-and to see the questions it raises as fundamental in nature. Constantly my patients drive me to question, and constantly my questions drive me to patients-thus in the stories or studies which follow there is a continual movement from one to the other.

Studies, yes; why stories, or cases? Hippocrates introduced the historical conception of disease, the idea that diseases have a course, from their first intimations to their climax or crisis, and thence to their happy or fatal resolution. Hippocrates thus introduced the case history, a description, or depiction, of the natural history of disease-precisely expressed by the old word 'pathology.' Such

histories are a form of natural history-but they tell us nothing about the individual and his history; they convey nothing of the person, and the experience of the person, as he faces, and struggles to survive, his disease. There is no 'subject' in a narrow case history; modern case histories allude to the subject in a cursory phrase ('a trisomic albino female of 21'), which could as well apply to a rat as a human being. To restore the human subject at the centre-the suffering, afflicted, fighting, human subject-we must deepen a case history to a narrative or tale; only then do we have a 'who' as well as a 'what', a real person, a patient, in relation to disease-in relation to the physical.

The patient's essential being is very relevant in the higher reaches of neurology, and in psychology; for here the patient's personhood is essentially involved, and the study of disease and of identity cannot be disjoined. Such disorders, and their depiction and study, indeed entail a new discipline, which we may call the 'neurology of identity', for it deals with the neural foundations of the self, the age-old problem of mind and brain. It is possible that there must, of necessity, be a gulf, a gulf of category, between the psychical and the physical; but studies and stories pertaining simultaneously and inseparably to both-and it is these which especially fascinate me, and which (on the whole) I present here-may nonetheless serve to bring them nearer, to bring us to the very intersection of mechanism and life, to the relation of physiological processes to biography.

The tradition of richly human clinical tales reached a high point in the nineteenth century, and then declined, with the advent of an impersonal neurological science. Luria wrote: 'The power to describe, which was so common to the great nineteenth-century neurologists and psychiatrists, is almost gone now. It must be revived.' His own late works, such as The Mind of a Mnemonist and The Man with a Shattered World, are attempts to revive this lost tradition. Thus the case-histories in this book hark back to an ancient tradition: to the nineteenth-century tradition of which Luria speaks; to the tradition of the first medical historian, Hippocrates; and to that universal and prehistorical tradition by which patients have always told their stories to doctors.

Classical fables have archetypal figures-heroes, victims, martyrs, warriors. Neurological patients are all of these-and in the strange tales told here they are also something more. How, in these mythical or metaphorical terms, shall we categorise the 'lost Mariner', or the other strange figures in this book? We may say they are travellers to unimaginable lands-lands of which otherwise we should have no idea or conception. This is why their lives and journeys seem to me to have a quality of the fabulous, why I have used Osier's Arabian Nights image as an epigraph, and why I feel compelled to speak of tales and fables as well as cases. The scientific and the romantic in such realms cry out to come together-Luria liked to speak here of 'romantic science'. They come together at the intersection of fact and fable, the intersection which characterises (as it did in my book Awakenings) the lives of the patients here narrated.

Next page