CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

A big thanks to all who helped, and especially Marie France for watering the seeds; James Warren for feeding the soil; John Thornton of the Spieler Agency for his steady care; Mark Newell for the wisdom of the seanchai; Sue Warga and Amy Brosey for superb copyediting; Philip Rappaport, my editor at Bantam, for believing in this story all the way; and finally to Alan Green, the first to encourage me, for showing me that the marathon is run one step at a time.

PART I

THE TWISTED STRAND

CHAPTER ONE

AWAY WITH THE FAIRIES

I ts dark and murky inside Irelands Cave of the Cat. A muddy abyss in the heart of bog Ireland, the Cave of the Cat, or the Oweynagat, as its known, is no ordinary grotto. A royal shrine in the second century, this natural limestone fissure was said to be a local doorway to the otherworld of the fairies, a race of paranormal beings reputed, among other things, to possess the minds of the insane.

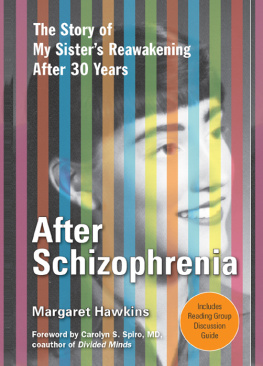

I crept in here just before midnight, searchingvainly, I suspectfor clues to the madness that has mauled my family for generations: the victims include two of my four sisters, along with one uncle, one grandmother, and her great-grandmother before her, a perfect storm of schizophrenia that follows a maternal line stretching from Boston back here to County Roscommon, our ancestral homeland.

Inside the cave, the silence is split only by the drip-drop of water, the emptiness of the place and the steady pounding drip unleashing in me small pangs of paranoia. But the limestone is my lodestone, drawing me into its black depths because this is as far back as the fairy myths of madness go in Ireland. According to 1,100-year-old manuscripts, the sidhe (pronounced shee)the mischievous fairy people who capture minds from those who lose themset the nearby palaces of mortals afire and ran into this cave. Its all too fantastic to believe, but Im trying to be receptive.

Unlike those Irish Americans who dig after genealogical clues, I have no sentimental attachment to my forebears. Instead, I feel Im chasing much bigger game here, stalking the madness that stalks my family in a direct line down tobut not includingme. Of all the caves in Ireland (and there are thousands), the Oweynagat is the one that gets the most attention in the early Irish literature. Psychotic cats, a symbol of the devil in ancient Ireland, were said to prowl the countryside from here; curses were probably cast here as well by robed Druids, the old wizard priests of Ireland who gathered at this spot for royal pagan feasts. Back when all madness was seen as a punishment, as payback for crossing some deityfirst pagan and then Christianso phantasmagoric were the myths surrounding this cave that to step into its darkness was to enter Irelands hellmouth.

Im here with my own hellish story of sorts, because I know of at least three ancestors who sufferedas two of my fifth-generation Irish American siblings do nowfrom schizophrenia, a savage psychosis for which there is no cure or effective treatment. Statistics reveal that one of every four people worldwide suffers from some type of mental illnessone in one hundred from schizophrenia, the most severe form, its victims typically tortured by voices and other hallucinations that give rise to bizarre and demented behavior. I pick my steps carefully, groping in the darkness for the widening cave walls, yet my quest feels as slippery as the muddy clay floor that dips then rises toward the neck of this bottle-shaped chamber.

The fairy cave and a massive network of Druid ring forts that surround it are a short distance north of where my mothers sideour schizophrenic sidehails from, an area thick with archaeological sites that hold secrets of the past. Tonight is Halloween, known here for thousands of years as the Samhain (pronounced sow-when). The pagan new-year feast day, the Samhain in Ireland marks a fresh start for the year ahead. But its also that most bewitched evening of the Celtic calendar, the Feast of the Dead, when the veil dividing our world from the next is thought to be at its thinnest. Of the four major pagan festivals, the Irish are most uneasy about this one, with mortals going to the otherworld and the dead returning here. It is said that tonight, from here at the stroke of midnight, our ancestral ghosts are let loose to roam the earth.

As the hour nears, I cant help wondering about the haunts of my own schizophrenic lineage. The thought of them lurking here in the caves darkness gives me the shivers. One might be Mary Egan, who limped out of bog Ireland, a twenty-four-year-old already driven insane in the midst of the Great Famine that pushed her with her husband, John, to Boston. Or so goes the family lore.

Another schizophrenic ghost might be her great-granddaughter, my grandmother May Sweeney White. She never set foot in Ireland, but her gene string stretches back here to Mary Egan and forward in time, with little mutation, to my mothers brother and two of my four sisters. We are a busy nest of schizophrenia, all wrapped up in a twisted strand of DNA. I count myself as a genetic near miss. But for the sake of the next generation, Im out here probing the hereditary horizons, monitoring the schizophrenic frontier. And this cave is as close as Ill ever get to the psychic origins of the mysterious voices that afflict my family like nearly no other.

To my mind, May Sweeneys story was the scariest and therefore probably the most schizophrenic of all. Her incident, as my mother called it, happened on a crisp autumn day in 1924. There was already some doubt about Mays rickety state of mind that morning, but by evening it was obvious that she was the latest victim. The twenty-nine-year-old mother of six must have thought it was a special day, because she picked out her best outfita dark shawl thrown over a chiffon dress, a velvet cloche hat, and a pearl necklace. Slipping on a pair of white kid gloves, and without leaving a note, the poised-looking beauty set off through the leafy streets of Providence, just an hours drive down the old Post Road from Boston.

No one saw her slip out for the day, and by twilight her husband had grown worried. Jack White waited at their modest Hannah Street bungalow in the heart of the Olneyville section of town, watching from the window in the gathering dusk. Normally, Big Jack was a sea of calm, but today he was concerned for a host of reasons. For one, May had not been eating properly; for another, it was past sunset and unsafe in the city at night, and it was not like a young woman to stay out so late, her whereabouts unknown. Out in the unlit parts of the neighborhood or on the hidden banks of the river, bad things were known to happen. Mostly, though, it was that May had not been herself lately. Once cheerful and lighthearted, shed grown aloof and lifeless in the months since her sixth child was born. The melancholya listless sort of head fog that had come over hernow hung like a dark bank of clouds.

At last Jack sees Mays figure approaching in the darkness. In her white-gloved finery, she moves up the walkway. But something is amiss: she is clutching her shoes; her hat is cocked, her makeup smudged. May stands in the middle of the road, her shoeless feet swollen and reddened, hard-worn, it would seem, from hours of walking. She says nothing, but as Jack goes out the gate to meet her, her slow grin says it all: every tooth has been wrenched from Mays headher gums a swollen and bloody mess.

Next page