CONTENTS

Landmarks

Print Page List

ALSO BY GREGORY SCOFIELD

The Gathering: Stones for the Medicine Wheel

Native Canadiana: Songs from the Urban Rez

Love Medicine and One Song

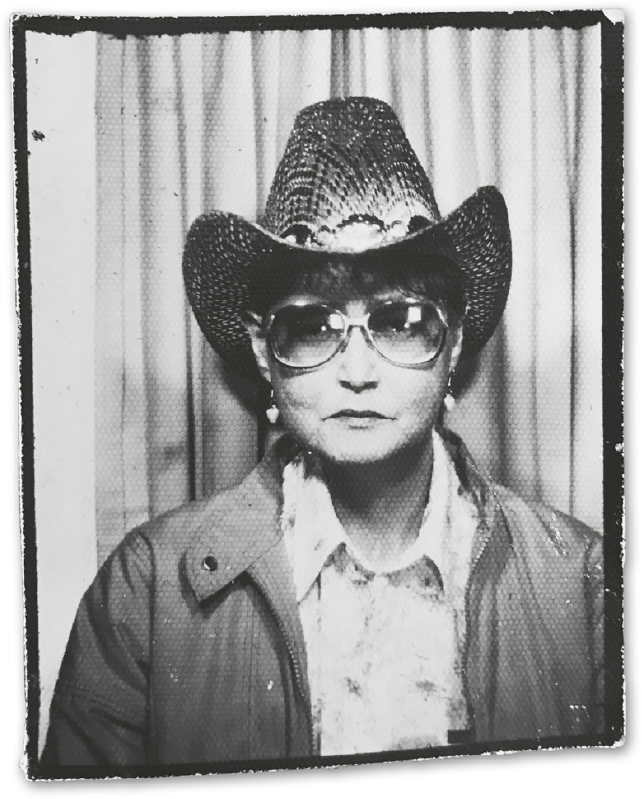

I Knew Two Mtis Women: The Lives of Dorothy Scofield and Georgina Houle Young

Singing Home the Bones

kipocihkn: Poems New and Selected

Louis: The Heretic Poems

Witness, I Am

With gratitude to Silas White for helping to shape the story.

Anchor Canada edition published 2019

Copyright 1999 Gregory Scofield

All rights reserved. The use of any part of this publication, reproduced, transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, or stored in a retrieval system without the prior written consent of the publisheror in the case of photocopying or other reprographic copying, license from the Canadian Copyright Licensing agencyis an infringement of the copyright law.

Anchor Canada is a registered trademark.

Cree words and phrases used in this book have been spelled in their standardized roman orthography.

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Scofield, Gregory, 1966- author.

Thunder through my veins : a memoir / Gregory Scofield.Anchor Canada edition.

Originally published: Toronto: HarperFlamingo Canada, 1999.

ISBN 978-0-385-69274-8 (softcover)

ISBN 978-0-385-69275-5 (EPUB)

1. Scofield, Gregory, 1966- Childhood and youth.

2. Poets, Canadian (English)20th centuryBiography

3. MtisBiography. I. Autobiographies.

PS 8587. C 614 Z 53 2019 C 811.54 C 2019-005520-0

Book design by Jennifer Griffiths

Cover images: (clouds) Mark Cerny / Getty Images; (prairie) Michael Bourgault / Unsplash

Published in Canada by Anchor Canada,

a division of Random House of Canada Limited,

a Penguin Random House Company

www.penguinrandomhouse.ca

v5.3.2

a

CONTENTS

For my mother, Dorothy Scofield, who taught me to persevere and to keep dreaming, no matter the darkness.

SO MUCH HAS changed in the twenty years since I first wrote this book. In fact, so much has changed, I hardly recognize myself in the pages of this story. My once fragmented world that was filled with ghosts and shadows is now a place of wholeness and clarity. Ive grown into the eyes left to me by my mother, my grandfather, and all the kht-ayak, the Old Ones, who led my feet forward when I couldnt find my way. Ive been blessed by their singing, nikamowin, when I couldnt hear my own voice. Ive been blessed by their laughter, phpiwin, when I was angry. But above all, Ive been blessed by the rattle of their bones, oskana. They have brought me to the lodge within myself where Ive been awoken by a new thunder, and where I am now home.

At the time, I wrote Thunder Through My Veins for all the young First Nations and Mtis kids whod grown up in a situation similar to mine. Id written it for those whod survived and for those who were still struggling. The book was meant to serve as a document of resilience. It was meant to provide hope where there was none. It was meant to offer a reflection where there was no mirror. It was meant to offer a voice where there was silence. And it was meant as a wake-up call for Canadians, a written account of the effects of colonization and societal indifference, and of the generational trauma and disconnection to family history and community as experienced by so many First Nations and Mtis people. However, in 1999, when Thunder Through My Veins was published, it seemed as if many Canadians were tired of traumatic Indian stories. This, of course, was nine years before the founding of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) and sixteen years before the TRC brought forward its findings and its ninety-four calls to action, many of which address historical injustices and the contemporary realities faced by Indigenous Peoples in Canada. After 2015, there appeared to be a genuine interest in Canadas relationship with Indigenous Peoples. For the first time, since the passage of the 1876 Indian Act and the 1884 amendment to the act, which made it compulsory for First Nations children to attend residential school, and including the 1885 ban of the Sun Dance and Potlatch, the Canadian government seemed committed to reconciliation. And, as more Canadians became aware of their own history and the effects of colonization, the more they began to read stories by, for and about Indigenous Peoples. Up until this point, Indigenous stories were largely seen as reaching a niche market, celebrated, of course, in our own circles, but somehow disconnected from the Canadian narrative and the founding history and the hard truths of this country.

Furthermore, the way in which Indigenous stories were edited for publication in the seventies, eighties and early nineties reflected a non-Indigenous gaze into the lives and experiences of First Nations and Mtis people. Stories were neatly tidied up of their too political aesthetic, rocking the boat only slightly insofar as truth telling. Stories were given relevance and authenticity not in how they communicated individual experiences but rather in how they upheld stereotypical tropes that had come to be expected by non-Indigenous publishers and readers. This is not to say, however, that Indigenous writers werent firmly established in the lexicon of Canadian literature. By the 1990s, a second wave of Indigenous writers, following in the footsteps of Lee Maracle, Jeannette Armstrong, Thomas King, Tomson Highway, Rita Joe, Basil Johnston, Daniel David Moses, Maria Campbell and Beatrice Mosionier, landed on the doorstep of CanLit. Suddenly, publishers and editors had to rethink their approach to Indigenous literature. Indigenous stories became full on, unapologetic stories of generational trauma and disinheritance, unflinching autobiographical narratives and fictional accounts of broken families and communities that spoke about Canadas true and undeniable past. Still, many readers were not prepared to listen. They opened the door to this history with trepidation and briefly looked at those of us standing on the other side, before slamming the door in our faces. It has taken another generation of Indigenous writers and artists to firmly place their feet in Canadas door, insisting it never close again.

Further to this, there were few stories other than Campbells Halfbreed and Mosioniers In Search of April Raintree that spoke specifically about Mtis culture, history and identity. For many Mtis people of my generation, we had few books in which we could see ourselves and even fewer stories in which we were present and visible as a distinct and autonomous nation. The idea of possessing both mixed Indigenous and European ancestry became further clouded in works like John Ralston Sauls A Fair Country: Telling Truths About Canada, in which he argues Canada, as a whole, is a Mtis nation. This, of course, implies that every Canadian with mixed Indigenous and European ancestry, is therefore Mtis. However, what is left out of this paradigm is the historical fact that the French Mtis, many with Francophone roots to Quebec, as well as the English/Scottish halfbreeds, many with roots to the Orkneys, have specific cultural, political and familial ties to the historic Red River Settlement in Manitoba and to Western Canada, which was largely based around the fur trade. And so, it appears by the mid-nineties anyone with mixed Indigenous ancestry, no matter the Indigenous nation to which they came from or how remote their ancestry, began to appropriate the term Mtis. This is problematic for many reasons, but namely in that it further erases Mtis identity specific to Western Canada.