Title Page

THE MIGHTY EIGHTH IN THE SECOND WORLD WAR

By

Graham Smith

Publisher Information

First Published in 2001 by

Countryside Books

3 Catherine Road

Newbury, Berkshire

www.countrysidebooks.co.uk

Digital edition distributed in 2014 by

Bookmasters, Inc.

www.bookmasters.com

Graham Smith 2001

All rights reserved.

No reproduction permitted without the prior permission of the publisher.

The cover painting by Colin Doggett shows B-17Gs of the 350th Bomb Squadron of the 100th Bomb Group in early 1945.

Designed by Mon Mohan

Produced through MRM Associates Ltd., Reading

Dedication

This book is humbly dedicated to all those young airmen of the Eighth Air Force who served during the Second World War, in honour of their determination, courage and sacrifice.

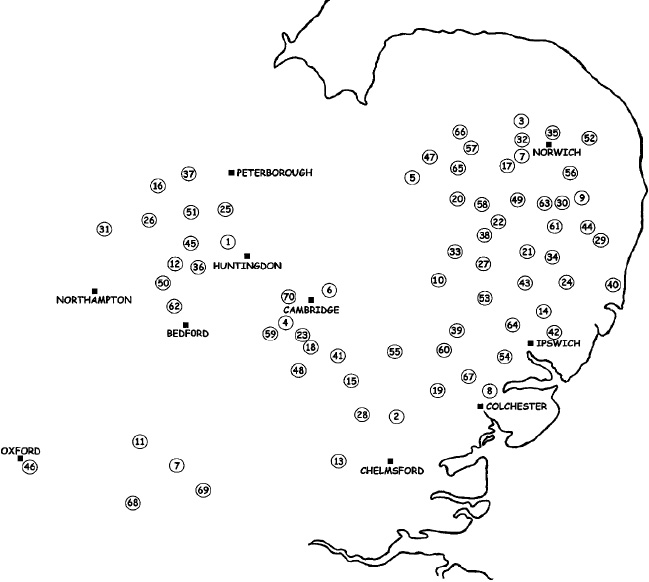

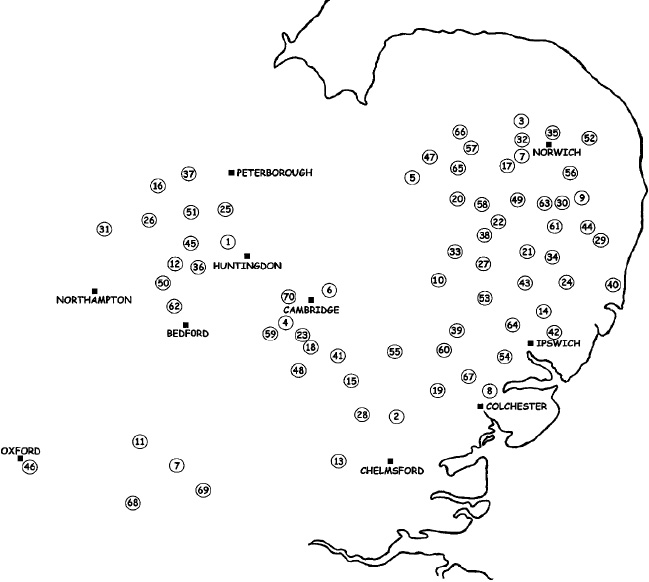

Map of Eighth Air Force Airfields

Key to Airfields

1. Alconbury.

2. Andrews Field.

3. Attlebridge.

4. Bessingbourn.

5. Bodney.

6. Bottisham.

7. Bovingdon.

8. Boxted.

9. Bungay.

10. Bury St Edmunds.

11. Cheddington.

12. Chelveston.

13. Chipping Ongar.

14. Debach.

15. Debden.

16. Deenethorpe.

17. Deopham Green.

18. Duxford.

19. Earls Colne.

20. East Wretham.

21. Eye.

22. Fersfield.

23. Fowlmere.

24. Framingham.

25. Glatton.

26. Grafton Underwood.

27. Great Ashfield.

28. Great Dunmow.

29. Halesworth.

30. Hardwick.

31. Harrington.

32. Hethel.

33. Honington.

34. Horham.

35. Horsham St Faith.

36. Kimbolton.

37. Kings Cliff.

38. Knettishall.

39. Lavenham.

40. Leiston.

41. Little Walden.

42. Martlesham Heath.

43. Mendlesham.

44. Metfield.

45. Molesworth.

46. Mounts Farm.

47. North Pickenham.

48. Nuthampstead.

49. Old Buckenham.

50. Podington.

51. Polebrook.

52. Rackheath.

53. Rattlesden.

54. Raydon.

55. Ridgewell.

56. Seething.

57. Shipham.

58. Snetterton Heath.

59. Steeple Morden.

60. Sudbury.

61. Thorpe Abbotts.

62. Thurleigh.

63. Tibenham.

64. Wattisham.

65. Watton.

66. Wending.

67. Wormingford.

Also

68. 8th A.F. H.Q.

69. 8th F.C. H.Q.

70. Military Cemetery & Memorial, Madingley.

Acknowledgements

I am deeply indebted to a number of people for assisting me during the preparation of this book, especially with the provision of illustrations.

First and foremost, I must thank Norman G. Richards of the Archives Division of the NASM. Over the last six years, Norman has been unstinting with his time and patience in answering all my enquiries regarding the USAAF, particularly concerning the selection of illustrations. From being a most reliable and diligent correspondent, Norm has become a true friend.

I would also like to thank Rusty Bloxom, Chief Historian of the Mighty Eighth Heritage Museum for his assistance, along with Tom Lubbesmeyer of the Historical Archives of Boeing Co. The Staff of Galleywood Library have again willingly helped in obtaining specialist books. The 398th Bomb Group, via Wally Blackwell in Rockville, Maryland, has kindly granted me permission to reproduce the verse that appears on their Group Memorial at Nuthampstead.

Graham Smith

Lieutenant James and some of his crew of B-17 `Home James of 457th Bomb Group at Glatton, after completion of their 25th mission on 31st May 1944. (USAF)

Introduction

Military aviation in the United States can be traced back to March 1898 when the War Department allocated $50,000 to fund Professor Samuel P. Langleys experiments to build a manned flying machine which would have practical application in war. On 8th December 1903 Langleys machine, Aerodrome , powered by a petrol engine, failed for a second time; the US Government withdrew its support and the project was abandoned. Just nine days later the Wright brothers completed their epic flight in Flyer entirely without any military or government funding.

By 1907 the Signals Corps of the US Army had decided that powered flight might indeed have some military potential. On 1st August it established an Aeronautical Division under Captain Charles Chandler, to have charge of all matters pertaining to military ballooning, air machines and all kindred subjects, heralding the birth of American military aviation. The next step was to obtain a suitable heavier-than-air flying machine that could be developed for military purposes. The US Army specified that it should be able to carry two airmen with sufficient fuel to remain in the air for 125 miles and be capable of flying at least ten miles at a speed of 40 mph. Three tenders were received but only the Wright brothers delivered an aeroplane for testing. During September 1908 Orville Wright demonstrated the Model B biplane to Army officers and Government officials at Fort Meyer, Virginia. On 17th September Lieutenant Thomas E. Selfridge of the Signals Corps was taken up as a passenger. The biplane suffered a propellor failure and crashed; Wright was seriously injured and tragically Lieutenant Selfridge became the first passenger to die in an aircraft crash. Nevertheless the conviction in powered flight and its potential for military use had not weakened. In August 1909, the Aeronautical Division obtained its first Wright biplane at the price of $25,000 plus a $5,000 bonus because it exceeded 40 mph! As a precursor of all those personalised American Second World War aircraft, this aeroplane was later called Miss Columbia .

Over the next two years a number of Army personnel were taught to fly at the Wright brothers school, but it was not until March 1911 that Congress approved the first funds ($125,000) specifically for the purchase of flying machines. During April 1912 aeroplanes were used on US Army manoeuvres for the first time, and in March 1913 several aviators and aeroplanes moved to Galveston Bay, Texas, ready for possible service along the border with Mexico. They were provisionally formed into the First Aero Squadron, later officially established as an Army squadron at San Diego, California, where the Signal Corps Aviation School was formed. On 18th July 1914 the renamed Aviation Section of the Signals Corps was given full responsibility for all US Army flying, with 60 officers and 260 enlisted men and a budget of $250,000.

Military aviation and aircraft production in Europe was given a massive boost with the outbreak of war, whereas US Army flying lagged far behind; it then ranked 14th in the world. When the United States declared war on Germany on 6th April 1917, the Aviation Section had fewer than 300 aeroplanes, none of which could be considered suitable for combat, and merely 35 qualified pilots, with only seven squadrons.

Since March 1916 a number of American pilots had been flying in France with the French Aviation Militaire in a unit originally named the Escadrille Americaine , later changed to Escadrille Lafayette . These airmen pre-empted the volunteer American pilots that served in the three RAF Eagles squadrons in World War II. In February 1918 the Escadrille Lafayette , as the 103rd Pursuit Squadron, was incorporated into the Aviation Section, which on 24th April was renamed the Army Air Service.

Although the US Government had boldly announced that it would build 40,000 military aeroplanes in one year, they never materialised and no American-designed aeroplanes flew in combat during the First World War. General Dunwoody, responsible for aviation procurement, remarked, We never had a single plane that was fit to use! The nascent US aircraft industry concentrated on trainers, including the famous Curtiss Jenny . The British de Havilland 4 was built under licence in the States powered by the American Liberty 12 engine; the first Liberty machine was completed in February 1918, but only 20% of 3,225 D.H.4s built in the US actually went to the Western Front; Handley Page 0/400 and Caproni night-bombers were also built under licence.

Next page